Alexander Campbell, His Travels, and the Border Piping Tradition

By IAIN MacINNES

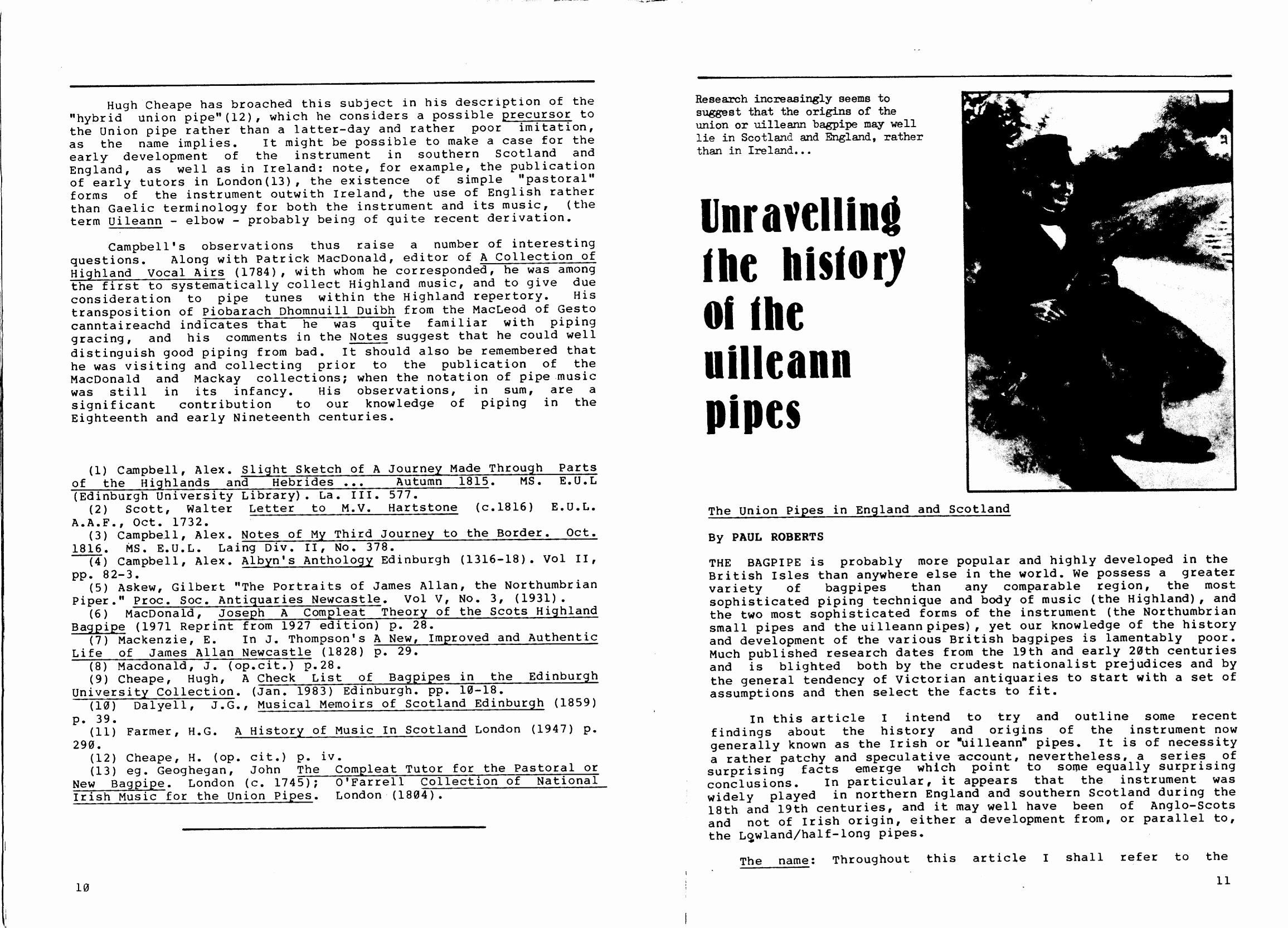

Alexander Campbell, (on right, playing bagpipes) figures in this drawing by the famous Edinburgh caricaturist, John Kay. 'A Medley of Musicians' was Kay's retaliation against a caricature Campbell drew of him, itself a repone to Kay's drawing of Campbell's brother.

HIGHLAND pipers are familiar with Alexander Campbell (1764-1824), editor of Albyn's Anthology, through his admiring description of Donald Ruadh MacCrimmon:

“after a few glasses of his own good tody, MacCrummin seized the pipe - put on his hat (his usual custom) - breathed into the bag - tuned the drones to the chanter - gave a prelude in a stile of brilliancy that flashed like lightning - and commenced Failte Phrionnsa in tones that spoke to the ear and affected the heart."(1)

Campbell, fortunately, was of a literary bent and frequently put pen to paper to record his expeditions to the Highlands and the Borders. In his early days as a music teacher and organist in Edinburgh he published a number of his own songs and poems, followed in 1798 by An Introduction to the History of Poetry in Scotland which contained a dissertation on Scottish music, favourably received by foreign musicians. Further literary endeavours, however, met little acclaim, and it was rather his talents as a collector and publisher of Highland music for which he is now remembered. As Walter Scott said of him, he was "a good musician, accurate in taking down music from singing, and indefatigable in collecting it - an enthusiastic, good, humble Highlander besides ..." (2)

For the piper two of his manuscript volumes are of particular interest. The first is his Slight Sketch of a Journey Through Parts of the Highlands and Hebrides; undertaken to collect materials for Albyn's Anthology; in Autumn 1815. This work is in effect a Report to the Royal Highland Society of Scotland, which sponsored his journey (to the tune of thirty pounds), and includes a description of his historic meeting with Donald Ruadh MacCrimmon; a description of Archibald MacArthur playing in the cave of Staffa - “awfully sublime"; and an account of a dinner in Boisdale, South Uist, where the Laird's piper struck up "and we had the double gratification of good cheer and excellent piping."

Notes of My Third Journey to the Border records another music quest in October 1816, ranging from Peebles to Liddesdale and back. (3)

At Traquair he encountered the pipes: "In the evening James Cockburn, a native of Banffshire, appeared, an itinerant and wool gatherer. He had three varieties of bellows pipes - one, an Irish pipe, he performed but indifferently. I pricked down his set of Malcolm Caird's come again." This eventually appeared in Albyn's Anthology (1816-18) under the title Donald Caird's Come Again, with words specially composed by Walter Scott. He reiterates the story of its collection, and says of Cockburn: “for his 'tails of woo' he paid but a spring o' the pipes; ‘for the Southanders,' he said, ‘are a’ unka guid sort o' bothies—and vera, very kind to me in trouth, on a' lawfu' occasions'." Scots words capture the spirit of the Caird:

"Donald Caird can lilt and sing, Blithely dance the Hieland fling, Drink till the gudeman be blind, Fleech till the gudewife be kind; Hoop a leglen, clout a pan, Or crack a pow wi’ any man; Tell the news in Burgh and Glen, Donald Caird's come again." (4)

Campbell then visited Abbotsford, and thence onward to Maxpopple, home of Walter Scott's uncle, Thomas Scott:

“On delivering my letter of introduction, the old gentleman seemed rather cold but civil, but he soon warmed and became easy, affable, and exceedingly communicative. He is full of anecdote, an excellent memory, vigorous grasp of mind and a lively imagination. Although four-score and five years, yet, except a little lame- ness in one leg, he is hale and healthy.

My business to Teviotdale being on the tapis, his son, Mr. James, tuned his pipe (an Irish pipe) and played in a very superior style, afterward the large Border bellows- bagpipe, on which he played with great spirit several of the well-known Border pieces. Then the old gentleman went upstairs for his own old pipes, and played several pieces in a style of particular excellence, after which we supped and retired to repose.

Monday, October 21st - Mr Thomas Scott performed many pieces on the pipe, two of which I noted down; after which I jotted down the particulars following regarding the best bagpipers of the Border, most of whom he himself knew personally.

A list of the best Border bagpipers (together with a few particulars regarding them) who lived from about the beginning of the year 1700 down till about the commencement of the year 1800, noted down from Mr Walter Scott's uncle, Mr Thomas Scott, presently resident at Monklaw, near Jedburgh, 21st October 1816:-

l.-Walter Forsyth, piper to Mr Kerr of Littledean, Roxburghshire: he was an excellent performer.

2.-Walter Forsyth (son of the former) was gamekeeper to the then Duke of Roxburghe; the son was reckoned likewise a good piper. The third in succession of celebrated Border pipers was

3,-Thomas Anderson, by trade a skinner, in Kelso. The father and grandfather of Thomas Anderson were esteemed good performers on what is called the Border ox bellows-bagpipe. They lived about the close of the seventeenth century.

4.-Donald Maclean, piper at Galashiels (father to the well-known William Maclean, dancing- master in Edinburgh), was a capital piper, and was the only one who could play on the pipe the old popular tune of "sour Plums of Galashiels," it requiring a peculiar art of pinching the back hole of the chanter with the thumb, in order to produce the higher notes of the melody in question. He died about the middle of the eighteenth century. Richard

Lees, manufacturer in Galashiels, has the said William Maclean's bagpipes in his possession.

5,-John Hastie, piper of Jedburgh, lived about the year 1728 (see his elegy). He was the first performer who introduced those tunes now played in Teviotdale on the bagpipe. Mr Thomas Scott is decidedly of opinion that the Border bellows-bagpipe is of the Highland (or, at any rate, the north-east coast) origin, as all the pipers with whom he was acquainted positively declared. This is a remarkable fact, not generally known, and difficult of belief. The small Northumberland bagpipe differs considerably from the one alluded to, particularly in the mode of execution. The successor of John Hastie was

6.-Robert Hastie (newphew of the former). Mr Thomas Scott thinks that Hastie succeeded his uncle about the year 1731: he was reckoned a good performer.

7.-George Syme was supposed to have been born and bred in one of the Lothians. He was the best piper of his time; he knew the art of producing the high octave by pinching the back hole of the chanter, which was reckoned a great improvement. He was the best piper of his day. He lived about the middle of the eighteenth century.

The earliest pipers (Mr Thomas Scott says) of the Scottish Border, properly speaking, were of the name and family of Allen, who were born and bred at Yettam, in Roxburghshire. They were all tinkers. The late James Allen was piper to the Duke of Northumberland, and was the best performer on the loud and small bagpipes of his time. He being a Border lifter, the poor fellow was caught hold of in some of his lifting exploits, and cast into prison: but escaping justice, and set at large, he renewed his bye-jobs, was again incarcerated, and condemned to be hanged: which sentence was (at the solicitation of the Duchess of Northumberland) changed to imprisonment for life. He died in jail, at the advanced age of eighty years and upwards, about two months before his pardon came down from the king. This happened in the year 1888.

After jotting down the preceeding notices respecting the most celebrated pipers of the Border, I took my leave."

"Mr Robert Shortreed, Sheriff-Substitute of Roxburghshire, told me that the office of piper in Jedburgh had been suppressed some years since that when the piper accompanied by the town drummer played - especially in the evenings of the spring, summer, and autumn – the joyful group of matrons with their babies, and the little ones which followed the pipe and drum, was delightful to behold. - A.C."

Campbell was rare in being careful to distinguish between the different pipes he encountered - identifying the “Borders Bellows bagpipe", the "Irish Pipe", and the “loud and small" pipes of James Allan. Otherwise there is a general paucity of information. The instruments of town pipers may have ranged from the Border pipe to the full Highland pipe, with all variations in between, The statue of Habbie Simpson in Kilbarchan, for instance, shows him shouldering a mouth-blown, two-droned set; while portraits of James Allan variously depict mouth and bellows-blown Border pipes and small pipes. (5)

Campbell's passage shows that in the Eighteenth Century in the Borders, small pipes, Irish pipes, Border pipes, and possibly Highland pipes co-existed. Simple notions of the geographical integrity of the instruments are hence untenable, particularly as the practitioners on these varied forms were as frequently Borderers as far-flung wanderers from the Gaidhealtachd and Erinn.

The music, in consequence, must have shown considerable variety, although the Borderer may have been prone to incorporate some of his own technique into the playing of the other instruments. Indeed Campbell does distinguish between the tunes played by James Scott on the Irish pipe, and the "well-known Border pieces" - of which Sour Plooms of Galashiels is specifically mentioned.

As regards the Border pipe music, which I'm sure was distinct, certain provisos should be made. One is that, as with the vocal tradition, many melodies for the pipe share a common useage in the Lowlands, the Highlands, Ireland and even England - eg. "The Mason's Apron". Centuries of interaction have ensured a wide diffusion, and often it is the style and interpretation, rather than the actual melody, which differ.

Another cautionary note is that the Border music was dynamic and developing, and we should not necessarily seek norms in the music and expression, For instance, Campbell tells us that John Hastie (c.1720) "was the first performer who introduced those tunes now played in Teviotdale on the Bagpipe", which certainly implies innovation, Another commentator on the Lowland instrument, Joseph MacDonald (c.1760) found as its main fault its tendency to adapt music from other media. “In the Low Countrie where they use bellows to their pipes, they have enlarged the compass of it by adding pinching notes, for the better imitation of other music." He specifies "Scotch Tunes, minuets and Italian music."(6)

MacDonald's comments prompt the following line of speculation. Besides being played through the streets morning and evening, the Lowland pipe was very much a folk instrument, particularly suited to dancing. Mackenzie in the 1826s found it "extremely well calculated for playing that rustic species of music called reels"(7), and even MacDonald reluctantly admits that it was “tolerably well calculated for violin reels, and some pipe jigs; but of no great execution..."(8) Farmer has stated his belief that the bagpipe was one of the few folk instruments to survive the Reformation, and in that capacity it must have been called upon not only for marching tunes and dances, but also to accompany singing and keep abreast of the popular melodies of the day.

To that end it was necessary to expand the scale, which was achieved on the Northumbrian and Irish pipes by the addition of keys, and on the Border pipe by "pinching" or “shivering the back 1i11" to get the high B. The addition of only one note, however, taking the instrument into a fairly piercing register, could only have been of limited value.

The development of the Highland pipe in the meantime took a rather different course, In the post-Culloden resuscitation of the instrument, from the 1780s, the Great Pipe found itself isolated from the folk culture which had nurtured it, and cocooned instead on the expansive estates of the gentry, basking in the favour of Royalty. Certainly it was played for the march and the dance, but there was no expectation that it should reflect popular and changing Musical tastes; the reverse, rather, was true, for the Highland pipe was adopted as a symbol of clanship and past glory, and the “martial music of the clans" played on, not in the context of Gaelic Society, but rather to pander to Victorian sentiment.

The Border pipe, in contrast, enjoyed few of the advantages of aristocratic patronage, and compared poorly with the Highland pipe as a military band instrument, (one reason why there are now no pipe bands using bellows pipes). By the turn of the Nineteenth Century it’s use as a folk instrument must also have been in jeopardy, for it was by then in competition with fiddles, melodeons, keyed pipes and so on, all with greater compass and wider repertoires. I think the Border pipe probably was expected to reflect current musical taste, as well as playing “the well-known Border pieces", and in this respect it proved inadequate, to be superseded by more versatile instruments.

One final, connected point to emerge from Campbell's manuscript is the use of the "Irish Pipe" in the Borders, which may simply have reflected the piper's need to use an instrument of greater compass and sweeter tone than the Border pipe. This subject deserves fuller treatment elsewhere, for although the instrument even by Joseph MacDonald's time (1760) was labelled "Irish", it was in fact being manufactured in Scotland for Scotsmen to play.Eighteenth Century chanters made by Bannon and Donald MacDonald of Edinburgh are extant (9), while we hear of the Irish Pipe being cited as a stage instrument (16), and indeed being taught in Edinburgh, (by T. Campbell), probably towards the end of the Eighteenth Century. (11). It was not confined, either, to the Cosmopolitan capital, but played by itinerants from Banffshire and in the Border villages, and one wonders whether the tunes played on it were Irish, or simply common Scottish pieces which exceeded the range of other pipes.

Hugh Cheape has broached this subject in his description of the "hybrid union pipe"(12), which he considers a possible precursor to the Union pipe rather than a latter-day and rather poor imitation, as the name implies. It might be possible to make a case for the early development of the instrument in southern Scotland and England, as well as in Ireland: note, for example, the publication of early tutors in London(13), the existence of simple “pastoral” forms of the instrument outwith Ireland, the use of English rather than Gaelic terminology for both the instrument and its music, (the term Uileann - elbow - probably being of quite recent derivation.

Campbell's observations thus raise a number of interesting questions. Along with Patrick MacDonald, editor of A Collection of Highland vocal Airs (1784), with whom he corresponded, he was among the first to systematically collect Highland music, and to give due consideration to pipe tunes within the Highland repertory. His transposition of Piobarach Dhomnuill Duibh from the MacLeod of Gesto canntaireachd indicates that he was quite familiar with piping gracing, and his comments in the Notes suggest that he could well distinguish good piping from bad. it should also be remembered that he was visiting and collecting prior to the publication of the MacDonald and Mackay collections; when the notation of pipe music was still in its infancy. His observations, in sum, are a significant contribution to our knowledge of piping in the Eighteenth and early Nineteenth centuries.

(1) Campbell, Alex. Slight Sketch of A Journey Made Through Parts of the Highlands and Hebrides ... Autumn 1815. MS.

E.U.L (Edinburgh University Library). La. ITY. 577.

(2) Scott, Walter Letter to M.V, Hartstone (c.1816) E.U.L. A.A.F., Oct. 1732.

(3) Campbell, Alex. Notes of My Third Journey to the Border. Oct. 1816. MS. E.U.L. Laing Div. II, No. 378.

(4) Campbell, Alex. Albyn's Anthology Edinburgh (1316-18). vol II, pp. 82-3.

(5) Askew, Gilbert "The Portraits of James Allan, the Northumbrian Piper." Proc. Soc. Antiquaries Newcastle. Vol Vv, No.

3, (1931).

(6) MacDonald, Joseph A Compleat Theory of the Scots Highland Bagpipe (1971 Reprint from 1927 edition) p. 28.

(7) Mackenzie, E. In J. Thompson's A New, Improved and Authentic Life of James Allan Newcastle (1828) p. 29.

(8) Macdonald, J. (op.cit.) p.28.

(9) Cheape, Hugh, A Check List of Bagpipes in the Edinburgh University Collection. (Jan. 1983) Edinburgh. pp. 16-18.

(10) Dalyell, J.G., Musical Memoirs of Scotland Edinburgh (1859) p. 39.

(11) Farmer, H.G. A History of Music In Scotland London (1947) p. 298.

(12) Cheape, H. (op. cit.) p. iv.

(13) eg. Geoghegan, John The Compleat Tutor for the Pastoral or New Bagpipe. London (c. 1745); O'Farrell Collection of National Irish Music for the Union Pipes. London (1804).