A Tune for All Sessions

Jock Agnew explores the fine art of fitting bellows pipes into informal playing sessions. Can the piper really call the tune?

BACK IN 1999, Dick Edie wrote about “Session Etiquette” (Common Stock Vol 14, No 2). A year later Donald Lindsay contributed “Playing Along on the Smallpipes’” (Common Stock Vol 15 No 2).

Since then the world has moved on. The LBPS has published two books of tunes - (Suggested) Session Tunes and (Suggested) Duets and Harmonies. These tune books have, I believe, helped to encourage further the playing of Border pipes and Scottish smallpipes in sessions of one sort or another.

What, then, is meant by “a session”? Well how about this for a definition: “Two or more instruments playing along with each other in an ad hoc fashion, choosing tunes that fancy, familiarity or accessibility dictate.”

Which means that a largely unpredictable series of tunes will find themselves under the fingers of the musicians, which in turn means that written music is virtually impossible to use. (A group of musicians, all with music stands and music books which they hurriedly rifle in a desperate attempt to find the session tune of the moment is, in my opinion, a sad sight... I’ve seen it.)

So, in order to join in with the others, we are hoping to hear

- tunes that we already know, or

- tunes that are somehow familiar, though we may not have actually played them, or

- tunes sufficiently simple to follow along by ear even if we’ve never heard them

Where, then, do our smallpipes or Border pipes fit into this equation? Well, if the session consists only of pipers, then life is relatively simple. We know that everyone in the group shares the same restrictions of range and pitch, and possibly have a similar music source. And by following the fingers of other pipers we can keep time and even learn a new tune (if it is simple and not too fast). It is important, of course, that all the pipes are in the same key and, as Dick Edie points out, accurately pre-tuned to A440. At least then, if a stray note creeps in, it stands a good chance of creating a harmony rather than a slate-scraping discord!

When we, as pipers, join other musicians, life becomes a tad more complicated. It can be difficult for smallpipes to make themselves heard, and the tunes (whether they are weel kent or not) may be played in unfamiliar (and for us, impossible) keys.

The range of notes used may far outstrip those available on our chanters - though Donald Lindsay’s article offers some useful ideas for helping to overcome that problem.

How, then, do we deal with all this? Well, part of the solution lies in how most sessions are conducted. It is, in my experience, usual for someone with a tune on their mind to grab their chance during a suitable lull and launch forth. Others then join in. So the bellows-pipe player has to be prepared, take his chance, take the plunge, and break into music when the opportunity presents - and let all follow who may.

So far, so good - but what tune does the piper choose?

Let us take a step back. It can be helpful, and sometimes essential, to know the scope and limitations of the other instruments .present. These can be grouped into wind, string and percussion.

The wind instruments might typically be whistles, flutes, recorders, accordions, melode- ons, concertinas, harmonicas.

The string instruments might be guitars, banjos, bouzoukis, mandolins, fiddles, harps, hurdy-gurdies. The percussion instruments might be anything from cymbals to spoons but it matters not - the pitch in which they play won’t affect the outcome.

Folk musicians tend to favour the key or keys that are most easily played and best suit their own particular instrument. And why not? New tunes are more easily followed when played in a familiar key.

The table below tries to highlight these keys. It is only a rough guide, so there are plenty of exceptions which I won’t detail:-

|

Instrument. |

Main Characteristics |

Key(s) most favoured |

|

Whistles |

Various pitches, usually D. Can over-blow. |

G, D, (A) |

|

Flutes |

Pitched nominally in C, fully chromatic |

C, G, D, A |

|

Recorders |

Usually in C or F. Can play accidentals |

C, G, D, (A) |

|

Accordions |

Button or keyboard. Same note in as out. |

C, G, D, A |

Melodeons 2 rows of buttons, usually pitched G and D (if 3 rows, 3rd row probably in A) Different note in as out

Concertinas 2+ rows of buttons usually C and G. Different note in as out

English Fully chromatic. Characteristic thumb holds. Same note in as out

Harmonica Can be in any pitch - usually C May be chromatic (with push button)

G,D (A)

C, G, (D)

C, G, D, A

C, G, (D)

Guitar 6 string. Capo allows any key to be simulated Any

Banjo 5 string. May need re-tuning at key change 4 string. Tuned as fiddle

G, D, (A) G, D, A

Bouzouki 4 pairs strings. May be tuned G, D, A, D G, D, (A)

Mandolin 4 pairs of strings tuned as the fiddle G, D, A (C)

Fiddle 4 strings tuned G, D, A, E G, D, A (C) Harp Levers or pedals make them fully chromatic. C, D, G, A Hurdy-gurdy Usually tuned to D or G D, G, C, G

( ) for the competent player

If the opportunity arises near the beginning of a session, I like to test the water by inviting someone (anyone), to give me an ‘A’. This serves as an early warning to those who have never previously played along with pipes, that they may be faced with tunes pitched in that key. It also allows me to see which musicians go straight for that note, which of them fumble it, and how many just sit looking slightly uncomfortable!

From the above table it may be seen that, as a whole, folk instruments thrive most happily in the key of G, with D as a possible second choice. Take pipes along that are pitched in Bb and you will probably have the floor to yourself - except for a guitar player or two. But be of good heart - you will get a round of applause when you’ve finished!

So what pitch of pipes are best for mixing with other instruments? If the pipes are in D, then tunes that are written in nominal D (starting and/or finishing on the three-finger note) will appear to the world at large to be in G, and that should please the melodeon pushers. However Donald Lindsay, in his article, says he found A pipes to be more suitable than those in D. For my part, I play Border pipes in A, choosing tunes in D if there are a lot of melodeons, and in A or D if there are plenty of stringed instruments.

Once the pitch is selected, a choice of tune will have to be made. I am fortunate enough to have played in sessions on both sides of the Border as well as overseas, and one or two common factors seem to emerge. Those who meet frequently for session playing usually have a core of regular tunes (Jimmy Allen in G is a hot favourite). Then there are those tunes that are familiar to the local folk scene - for instance Morris tunes. And there is nearly always somebody who will introduce an obscure jig at finger-dizzy speed to which the others can only sit and listen until it has run its course - then mark their relief with a round

of applause.

For my first time with a group I tend to try out melodies that may be familiar as song tunes. Skye Boat Song usually attracts other players along, and the tempo can be stepped up by following it with Bobby Shaftoe. Then there are those melodies that are associated with a theme tune - like Dark Island, or Katie Bairdie. Donkey Riding brings a glint of familiarity to the eye of those who play for Morris Dancing, even if it is pitched in the unfamiliar key of ‘A’, as does Wha Wadna Fecht for Charlie. Or how about playing a familiar old music- hall favourite like (dare I suggest it in the present company!) Camptown Races. And at Christmas time Good King Wenceslas or Infant Holy should encourage a seasonal atmosphere.

Here I must make a confession. I have put together a pack of seven laminated cards (keeps the beer stains at bay!) filled with the dots of 25 simple session tunes. Those in A are on one side of each card, those in D on the other. This acts both as a quick reminder for me (my mind usually goes blank when suddenly faced with the need to play something), and a possible prompt for other musicians who might like to see a dot or two of a new tune.

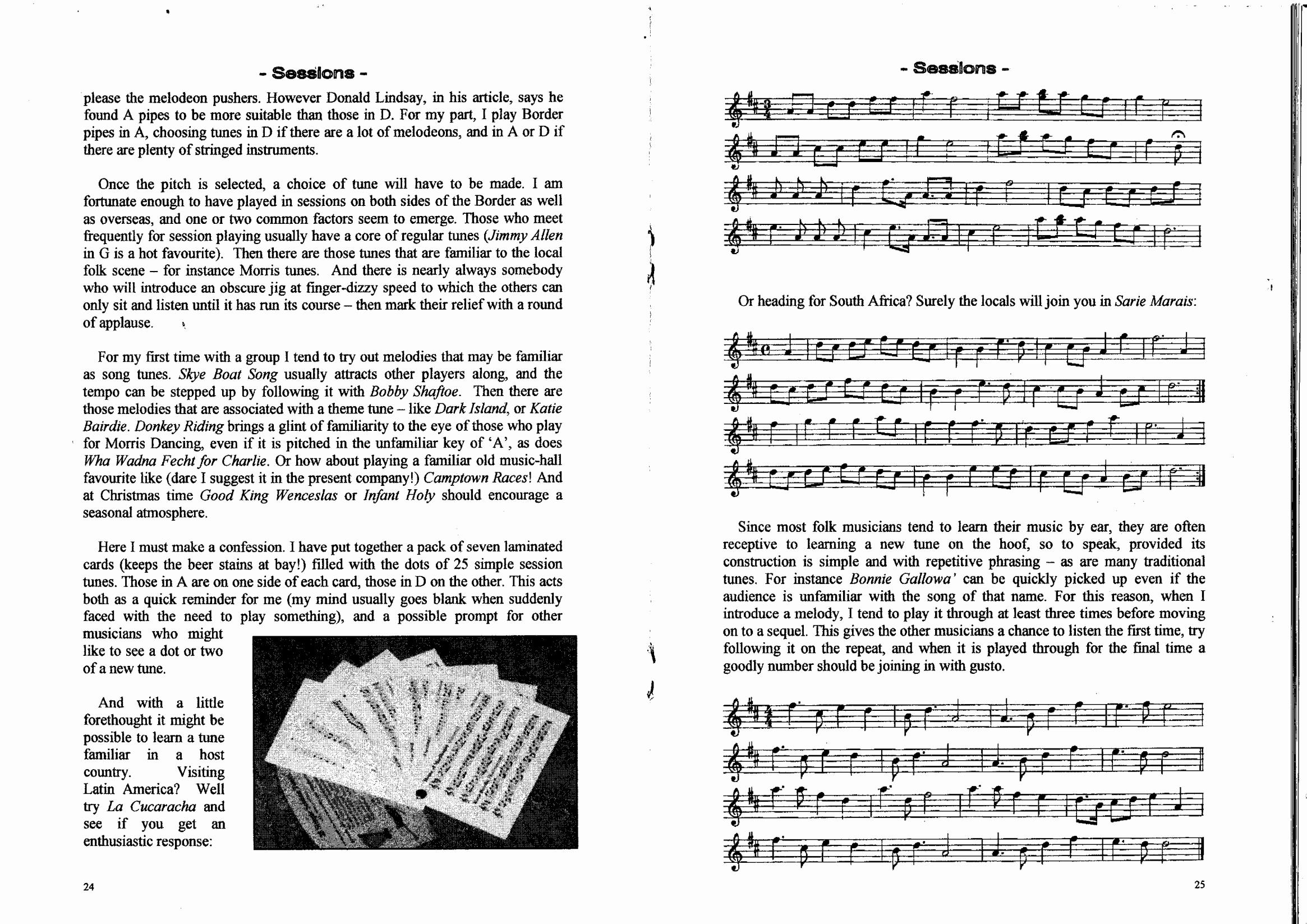

And with a little forethought it might be possible to learn a tune familiar in a host country. Visiting Latin America? Well try La Cucaracha and see if you get an enthusiastic response:

Or heading for South Africa? Surely the locals will join you in Sarie Marais:

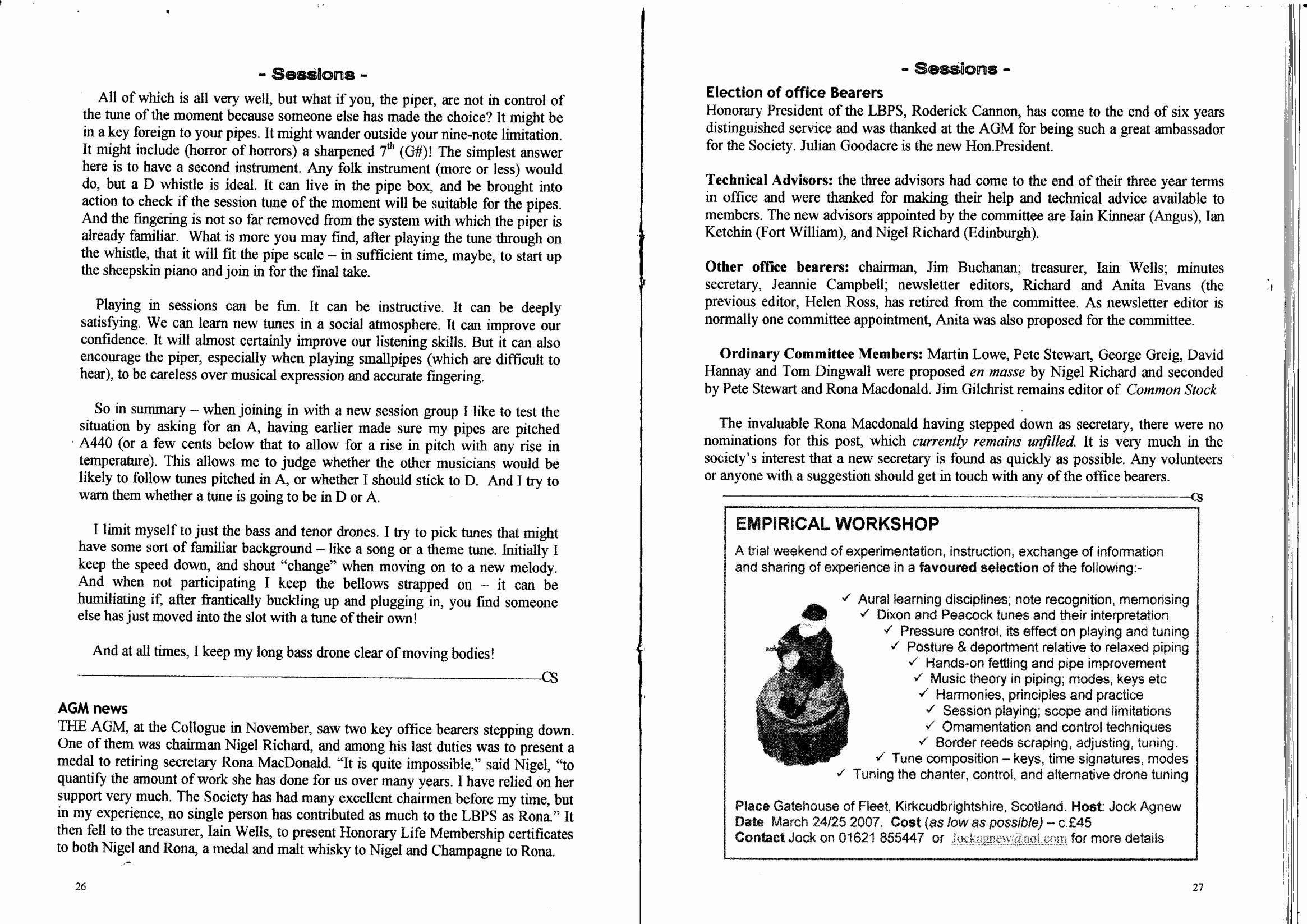

Since most folk musicians tend to learn by ear, they are often receptive to learning a new tune on the hoof, so to speak, provided it’s construction is simple and with repetitive phras- ing - as are many traditional tunes. For instance Bonnie Gallowa’ can be quickly picked up even if the audience is unfamiliar with the song of that name. For this reason, when I intro- duce a melody, I tend to play it through at least three times before moving on to a sequel.

This gives the other musicians a chance to listen the first time, try following it on the repeat, and when it is played through for the final time a goodly number should be joining in with gusto.

All of which is all very well, but what if you, the piper, are not in control of the tune of the moment because someone else has made the choice? It might be in a key foreign to your pipes. It might wander outside your nine-note limitation. It might include (horror of horrors) a sharpened 7th (G#)! The simplest answer here is to have a second instrument. Any folk instrument (more or less) would do, but a D whistle is ideal. It can live in the pipe box, and be brought into action to check if the session tune of the moment will be suitable for the pipes. And the fingering is not so far removed from the system with which the piper is already familiar.

What is more you may find, after playing the tune through on the whistle, that it will fit the pipe scale - in sufficient time, maybe, to start up the sheepskin piano and join in for the final take.

Playing in sessions can be fun. It can be instructive. It can be deeply satisfying. We can learn new tunes in a social atmosphere. It can improve our confidence. It will almost cer- tainly improve our listening skills. But it can also encourage the piper, especially when playing smallpipes (which are difficult to hear), to be careless over musical expression and accurate fingering.

So in summary - when joining in with a new session group I like to test the situation by asking for an A, having earlier made sure my pipes are pitched A440 (or a few cents below that to allow for a rise in pitch with any rise in temperature). This allows me to judge whether the other musicians would be likely to follow tunes pitched in A, or whether I should stick to D. And I try to warn them whether a tune is going to be in D or A.

I limit myself to just the bass and tenor drones. I try to pick tunes that might have some sort of familiar background - like a song or a theme tune. Initially I keep the speed down, and shout “change” when moving on to a new melody. And when not participating I keep the bellows strapped on - it can be humiliating if, after frantically buckling up and plugging in, you find someone else has just moved into the slot with a tune of their own!

And at all times, I keep my long bass drone clear of moving bodies!