A Return to Home Ground

A return to home ground

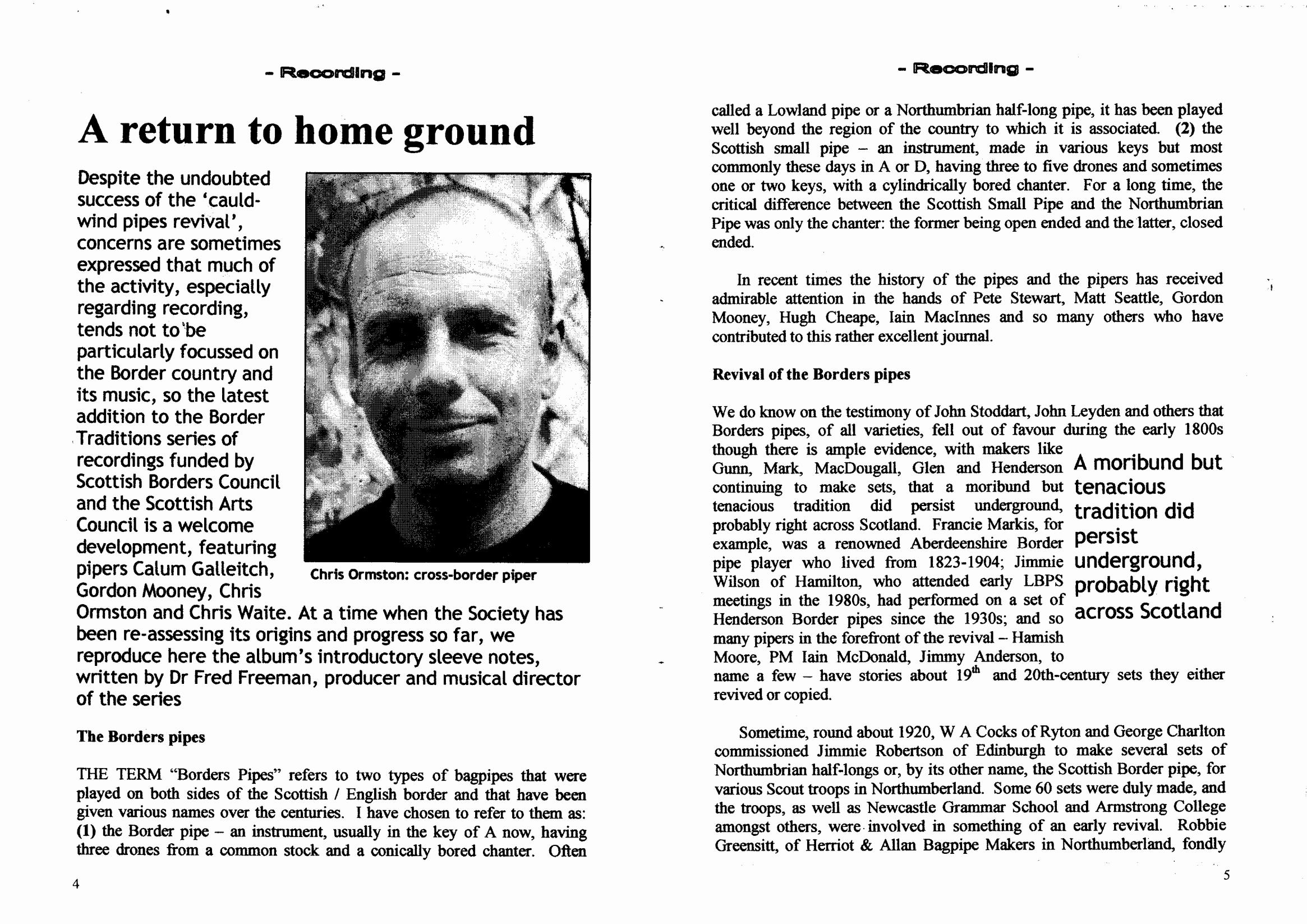

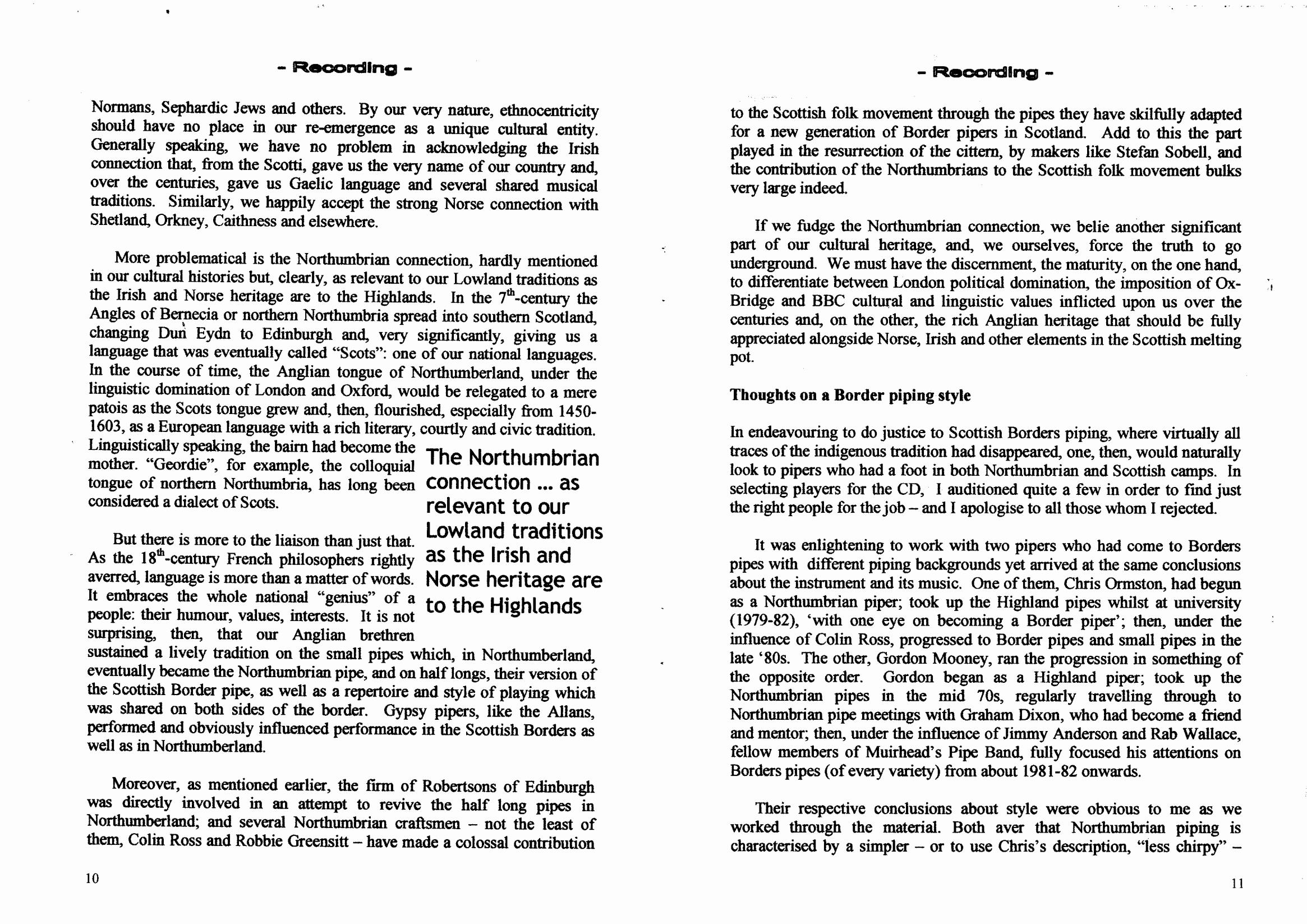

Despite the undoubted success of the ‘cauld- wind pipes revival', concerns are sometimes expressed that much of the activity, especially regarding recording, tends not to be particularly focussed on the Border country and its music, so the latest addition to the Border Traditions series of recordings funded by Scottish Borders Council and the Scottish Arts Council is a welcome develop- ment, featuring pipers Calum Galleitch, Gordon Mooney, Chris Ormston and Chris Waite. At a time when the Society has been re-assessing its origins and progress so far,

we reproduce here the album's introductory sleeve notes, written by Dr Fred Freeman, producer and musical director of the series.

The Borders pipes

THE TERM “Borders Pipes” refers to two types of bagpipes that were played on both sides of the Scottish / English border and that have been given various names over the centuries. I have chosen to refer to them as: (1) the Border pipe - an instrument, usually in the key of A now, having three drones from a common stock and a conically bored chanter. Often called a Lowland pipe or a Northumbrian half-long pipe, it has been played well beyond the region of the country to which it is associated. (2) the Scottish small pipe - an instrument, made in various keys but most commonly these days in A or D, having three to five drones and sometimes one or two keys, with a cylindrically bored chanter. For a long time, the critical difference between the Scottish Small Pipe and the Northumbrian Pipe was only the chanter: the former being open ended and the latter, closed ended.

In recent times the history of the pipes and the pipers has received admirable attention in the hands of Pete Stewart, Matt Seattle, Gordon Mooney, Hugh Cheape, Iain MacInnes and so many others who have contributed to this rather excellent journal.

Revival of the Borders pipes

We do know on the testimony of John Stoddart, John Leyden and others that Borders pipes, of all varieties, fell out of favour during the early 1800s though there is ample evidence, with makers like Gunn, Mark, MacDougall, Glen and Henderson continuing to make sets, that a moribund but tenacious tradition did persist underground, probably right across Scotland.

Francie Markis, for example, was a renowned Aberdeenshire Border pipe player who lived from 1823-1904; Jimmie Wilson of Hamilton, who attended early LBPS meetings in the 1980s, had performed on a set of Henderson Border pipes since the 1930s; and so many pipers in the forefront of the revival - Hamish Moore, PM Iain McDonald, Jimmy Anderson, to name a few - have stories about 19th and 20th-century sets they either revived or copied.

Sometime, round about 1920, W. A. Cocks of Ryton and George Charlton commissioned Jimmie Robertson of Edinburgh to make several sets of Northumbrian half-longs or, by its other name, the Scottish Border pipe, for various Scout troops in Northumberland. Some 60 sets were duly made, and the troops, as well as Newcastle Grammar School and Armstrong College amongst others, were involved in something of an early revival. Robbie Greensitt, of Herriot & Allan Bagpipe Makers in Northumberland, fondly remembers playing regularly on one of these sets, in the 1950s, with the 13th Whitley Bay, St Paul's Scout Pipe Band.

It was not, however, until later that a serious revival of the Border pipe and Scottish small pipe began to take shape within the Scottish folk movement. In the mid 1960s Jimmy Anderson of Larbert, who is generally, if unofficially, recognised as the founding father of the Scottish small pipe revival, began experimenting with Scottish chamber pipes and

practice chanters. Jimmy, who was a joiner to trade, borrowed wood from Bob Hardie to make wee drones and began plugging-up practice chanters and re-boring them with hand- made reamers in a desperate attempt to create an instrument that would sit nicely, alongside two fiddles and voice, in his group The Clutha. The Highland pipes were altogether too loud; the chamber pipes too soft; both were in B flat - not a great key for fiddlers.

Once a chanter was in hand, the critical problem was to find a suitable reed for it. In the late 60s and early 70s, Jimmy's friends and contemporaries in the folk scene - Rab Wallace, Iain MacDonald and others - would suggest his experimenting with cor anglais and bassoon reeds for the sound and projection he was seeking. Indeed, in the mid 70s, P/M Iain MacDonald (and Dougie Pincock after him) would use one of Jimmy's key of D prototypes, with the modified bassoon reed, in the noted folk band, Kentigern.

In the early 70s, Iain was given further impetus to play bellows bagpipes by one Willie Hamilton of Maryhill, Glasgow, who used to make Northumbrian and various Continental pipes on an old pedal Singer sewing machine. According to Iain, Willie would get Grainger & Campbell to make his long joints for the home grown Scottish Small Pipe he produced.

Being a Northumbrian pipe maker of considerable reputation, and a friend of Billy Pigg and Jack Armstrong, he experimented in the 1950s and 60s, with some degree of success, with a hybrid Northumbrian-Scottish reed for the Small pipe. On Willie Hamilton's death, his widow would pass on to Iain 17 sets of her husband's pipes - uilleann, pastoral, gaita, bombarde and more - which formed the original core of the large collection Iain now possesses. Willie Hamilton is more than a footnote to the revival.

Meantime, in 1975, according to Eddie Maguire, Rab Wallace would borrow a set of drawings of an old Border pipe from an Inverness museum and have it copied for playing in his group, The Whistlebinkies. He would also, by 1983, be performing with the ‘Binkies on a set of Jimmy Anderson small pipes in E flat, based upon a 19th-century set of MacDougall of Aberfeldy small pipes Jimmy saw in the Scottish National Museum.

Colin Ross, a Northumbrian pipe maker, who had taken note of Jimmy Anderson's early endeavours and, according to Jimmy, made “helpful” suggestions, began himself to puzzle over the reed problem. Moreover, in the late 70s, he had an order from a Liverpudlian for something he had never made before: a Scottish small pipe. After experimenting, unsuccessfully, with practice chanters and longer Northumbrian reeds, he decided, instead, to adapt the length of the chanter to the standard 2 inch Northumbrian reed size and, with that bit of technology, popularly advanced the revival of the Scottish Small Pipe by light years. He, then, began studying the design of old 18th century sets of Scottish Small Pipes from the Cocks Collection and adapted a design to suit the keys the modern folk pipers

wanted: mainly, D and A. Artie Tresize, Iain MacIinnes, Gordon Mooney and Hamish Moore would be amongst the performing pipers in the early 80s to play Colin's instruments. And, in fact, Hamish avers that it was primarily Colin who provided the sophisticated reed technology required to develop the Small pipes fully.

In the early 1980s, again in Northumberland, Robbie Greensitt, working independently, would develop the Border pipe in conjunction with Joe Hagan at J & R Glen bagpipe makers, Edinburgh, and, a few years later, would modify the design of the Scottish small pipe, in his words, “through adding both tone holes and evenly spaced holes on the chanter”. Richard Evans, a pupil of Colin Ross, also began making Scottish Small Pipes in 1980-81, initially with two metal keys on the chanter in order to play high B and high G sharp. In 1986, Jon Swayne of Glastonbury, following on from a design he saw in a book by Cocks, would, initially, develop a Border pipe in G for playing in his group Blowzabella.

Just a few years later, he would be making sets in A, with Highland fingering, for pipers in Scotland. Hamish Moore, for one, was impressed with Swayne's instruments, seeing them as amongst the first new generation Border pipe suitable for indoor ensemble playing.

A serious revival was underway. In 1974, Mike Rowan, after purchasing a set of North- umbrian half-longs at a Scout hall in Stockbridge, Edinburgh, began a quest to discover more about what appeared an unknown quantity: the Border Pipe. He, firstly, approached Hugh Cheape at the National Museum and, then, at Hugh's suggestion, Gordon Mooney.

With characteristic enthusiasm Mike organised his first formal meetings with Hugh and Gordon in 1981, designed a logo and founded the Lowland and Border Pipers Society in that year. Fortunately, he then discovered Jimmie Wilson of Hamilton who, to his mind, was “probably the last Lowland (Border) piper in the country to be taught by a Lowland piper”. Jimmie, as we mentioned earlier, had been performing publicly on a set of Henderson Border pipes since the 1930s - in shows like Johnny Armstrong, and, aside from his splendid wartime stories, had interesting things to say about the reeds and the instruments.

Several other noted makers gradually entered the fray: Julian Goodacre, Ray Sloan, Jon Swayne, Nigel Richard, Hamish Moore, to mention a few. Matt Seattle and Gordon Mooney would drive the movement forward with their excellent research and musical publications. The groups and soloists would enliven the Highland to small pipes whole Scottish folk movement with their performances and recordings: the Clutha, the Whistlebinkies, Kentigern, Gordon Mooney, Hamish Moore, Ceol Beag, Small Talk, Fred Morrison's various groups and more.

The rest is history. Hundreds of pipers round the world now play Scottish Borders pipes. As Hamish Moore put it, “no other movement has changed the face of piping, so quickly and so profoundly, within such a short space of time”.

The Northumbrian connection

In many respects the revival of the Scottish Border pipes reflects a larger social, political and cultural reawakening within Scotland. Vernacular traditions of language and the arts, either surviving underground for centuries or barely surviving at all, are now coming to the fore as Europe and the world begin to recognise the importance of minority cultures.

Nonetheless, with this recognition comes undeniable responsibility. Scotland is, and has always been, as Hamish Henderson put it, “a healthy hybrid”: a mix of Celts of all kinds, Angles, Vikings, Flemings, Normans, Sephardic Jews and others. By our very nature, ethnocentricity should have no place in our re-emergence as a unique cultural entity. Generally speaking, we have no problem in acknowledging the Irish connection that, from the Scotti, gave us the very name of our country and, over the centuries, gave us Gaelic language and several shared musical traditions. Similarly, we happily accept the strong Norse connection with Shetland, Orkney, Caithness and elsewhere.

More problematical is the Northumbrian connection, hardly mentioned in our cultural histories but, clearly, as relevant to our Lowland traditions as the Irish and Norse heritage are to the Highlands. In the 7th century the Angles of Bernecia or northern Northumbria spread into southern Scotland, changing Dun Eydn to Edinburgh and, very significantly, giving us a language that was eventually called “Scots”: one of our national languages. In the course of time, the Anglian tongue of Northumberland, under the linguistic domination of London and Oxford, would be relegated to a mere patois as the Scots tongue grew and, then, flourished, especially from 1450- 1603, as a European language with a rich literary, courtly and civic tradition. Linguistically speaking, the bairn had become the mother. “Geordie”, for example, the colloquial tongue of northern Northumbria, has long been considered a dialect of Scots.

But there is more to the liaison than just that. As the 18th century French philosophers rightly averred, language is more than a matter of words. It embraces the whole national “genius” of a people: their humour, values, interests. It is not surprising, then, that our Anglian brethren sustained a lively tradition on the small pipes which, in Northumberland, eventually became the Northumbrian pipe, and on half longs, their version of the Scottish Border pipe, as well as a repertoire and style of playing which was shared on both sides of the border. Gypsy pipers, like the Allans, performed and obviously influenced performance in the Scottish Borders as well as in Northumberland.

Moreover, as mentioned earlier, the firm of Robertsons of Edinburgh was directly involved in an attempt to revive the half long pipes in Northumberland; and several Northumbrian craftsmen - not the least of them, Colin Ross and Robbie Greensitt - have made a colossal contribution to the Scottish folk movement through the pipes they have skilfully adapted for a new generation of Border pipers in Scotland. Add to this the part played in the resurrection of the cittern, by makers like Stefan Sobell, and the contribution of the Northumbrians to the Scottish folk movement bulks very large indeed.

If we fudge the Northumbrian connection, we belie another significant part of our cultural heritage, and, we ourselves, force the truth to go underground. We must have the discernment, the maturity, on the one hand, to differentiate between London political

domination, the imposition of Ox- Bridge and BBC cultural and linguistic values inflicted upon us over the centuries and, on the other, the rich Anglian heritage that should be fully appreciated alongside Norse, Irish and other elements in the Scottish melting pot.

Thoughts on a Border piping style

In endeavouring to do justice to Scottish Borders piping, where virtually all traces of the indigenous tradition had disappeared, one, then, would naturally look to pipers who had a foot in both Northumbrian and Scottish camps. In selecting players for the CD, I auditioned quite a few in order to find just the right people for the job - and I apologise to all those whom I rejected.

It was enlightening to work with two pipers who had come to Borders pipes with different piping backgrounds yet arrived at the same conclusions about the instrument and its music. One of them, Chris Ormston, had begun as a Northumbrian piper; took up the Highland pipes whilst at university (1979-82), ‘with one eye on becoming a Border piper'; then, under the influence of Colin Ross, progressed to Border pipes and small pipes in the late ‘80s. The other, Gordon Mooney, ran the progression in something of the opposite order. Gordon began as a Highland piper; took up the Northumbrian pipes in the mid 70s, regularly travelling through to Northumbrian pipe meetings with Graham Dixon, who had become a friend and mentor; then, under the influence of Jimmy Anderson and Rab Wallace, fellow members of Muirhead's Pipe Band, fully focused his attentions on Borders pipes (of every variety) from about 1981-82 onwards.

Their respective conclusions about style were obvious to me as we worked through the material. Both aver that Northumbrian piping is characterised by a simpler - or to use Chris's description, “less chirpy” - gracing. In practical terms this meant that, in approach- ing the

Scottish Borders tunes, Chris has consciously worked to achieve, but in his own idiom, the simplicity of Northumbrian pipers like Tom Clough, who used “no open gracing”. Gordon describes the “conscious effort” he made in “removing heavy gracing ... freeing up the musicality”, after falling under the spell of Joe Hutton, Anthony Robb, Billy Pigg and other noted Northumbrian pipers. For Gordon Mooney, the historical linchpin of the tradition were the gipsy Border pipers, like the Allans, whose music and style survived in the Northumbrian tradition.

To my mind, the Borders instruments, generally, like the music itself, develop their intensity from a different source than Highland piping. Instead of the cut of birls, as in Crossing the Minch, or the compulsion, for example, of doubling and tachum variations, as in the penultimate section of Blair Drummond, the Borders pipes carry the listener along on a series of upward and downward runs and tickling leaps, as in Duns Dings A, Hey Ca Thro or Wee Totum Fogg. Moreover, the use of ornaments does not tend to follow a fixed pattern the way it does in Highland piping: eg, the wee doubling and birl tags at the end of each phrase in a Highland march. Instead, the Borders piper will use his ornaments sparingly and inconsistently, the way a tasteful uillean piper uses his regulators for varied expression. Listen intently on the album to Chris Ormston's use of tremolos in Cock Up Your Beaver or Chris Waite's use of them in Seventeen Minutes to Midnight, and you will see exactly what

I mean. There is no fixed pattern.

Incidentally, both Chris Waite and Calum Galleitch approached the instrument as Highland pipers - both mem- bers of Duns Pipe Band - who entered the Scottish folk sce- ne via sessions or modern folk ensembles. Chris's very free- form whistle playing has certainly helped in his adapting to the Border pipes. All four pipers agree with Hamish Moore's argument that greater “freedom” of performance and individual style are the order of the day. Both greater freedom and individual expression, Hamish reminds us, existed even in Highland piping before the Victorians and their successors standardised instrumental technique for the military pipe bands and society competitions.

A note on the musical arrangements

The musical arrangements are throughout, essentially, by myself, working in dialogue with the players. Pete Stewart, in his excellent study of the tradition, The Day It Daws, argues that the Borders pipes were indeed used as an ensemble instrument. Hamish Moore maintains that the whole “social context of the instrument has changed, from outdoor per- formance to the mixed session and folk band”. I have chosen to set the Borders Pipes in an ensemble context, where, to my mind, the moving contrapuntal lines are revealed in their best light.

The Tunes

For 300 years the Borders pipers - in Jedburgh, Hawick, Peebles and elsewhere - awakened the townsfolk and called them to their beds; performed for civic functions and common ridings; for weddings and dances, spontaneous rants in the fields and cemeteries. The tunes chosen for the CD reflect this lively range of musical activity. Without being too precious about it, one can affirm that some of these are indeed Border tunes that were played in the past; some of them might have been played; others just lie quite nicely on the Borders instruments. The splendid Burns tunes which I have chosen probably fall into all three categories.