Patronage, or the Price of the Piper's Bag

Patronage, or the price of the piper’s bag

Keith Sanger dispels some preconceptions as he looks at patronage and the roles of Highland and Lowland pipers

IN COMMON with all musicians, pipers required “patronage”, that is some form of reward in return for their service, be it provision of a house or land, a “salary” in the case of the burgh pipers, or an irregular cash income from playing for weddings and similar functions. As further evidence comes to light, it is becoming clear that there were no neat divisions into which the pipers method of “reward” can be placed. Even among the “Highland pipers”, the suggestion that they all received some land in return for “hereditary service” is increasingly requiring modification with the evidence showing a considerable variation in conditions of service between the different estates.

Among the “Lowland” pipers, especially where the information is derived from kirk session or the odd burgh record, their modern public image has tended to be somewhat lower than their corresponding Highland counterparts, but the deeper we dig, the more a somewhat different picture can be presented, at least when comparing like for like at the top end of the scale. Part of the problem arises from the fact that the description “chiefs piper” automatically sounds better than “burgh piper”, when it actually only reflects the fact that as there were few burghs within the Highland area, it was generally only the chief who could provide employment for a piper. It is interesting to note that of the two Highland burghs of Inverness and Inveraray, both actually had burgh pipers but with Highland names, and in the case of Inveraray in 1764, the piper John McIlchonnel was also a burgess and a local boat builder .(1)

In making any direct comparisons between the relative position and wealth of what are usually described as “Highland” or “Lowland” pipers, it is first necessary to have a fairly detailed picture of some pipers to compare here. The first is Alexander Fairly, who was burgh piper in Stirling during the second part of the 17th century He seems to have been one of a series of pipers in Stirling, starting with a Thomas Edmane in 1582,(2) John Forbes who flourished between 1598 to 1607,(3) Harie Livingstone on record in 1614,(4) James

Cowan, 1622,(5) John Buchanan, 1661 x 1664,(6) John Innis, 1672,(7) Alexander Fairly in 1675, Duncan Stalker in 1684,(8) and probably the last to hold the office, Alexander Glass who died in 1746.(9)

Several of these pipers were also granted burgess status, in the case of Cowan on his payment of £16, but with Fairly, Stalker and Buchanan for free, and Buchanan's “privilege” was also to be passed to his children. In 1668 another piper called John Benny was also granted burgess status for free, “for his service in the militia”, presumably a cost-free way of persuading him to help fill the burgh's military quota. (10)

There seems to have been a few years' break between Buchanan disappearing from the scene before John Innis was appointed in 1672, followed by Alexander Fairly who was appointed in 1675, and it is between that year and 1782 that there is an almost continuous run of the Stirling Common Good Accounts which provide the fullest record of a Burgh piper to date. Since he was not appointed a burgess until April 1679 and not all the pipers were granted that privilege, it would imply that it was not just something that Stirling automatically gave to its pipers and still had to be earned. The piper's salary was £20 per year, sometimes paid in one lump sum and at others, depending it would appear on the treasurer's whim, at half or quarter yearly increments.(11)

That salary was however just a base line and his total remuneration was worth much more when all allowances are taken into account. In 1675, he received a new instrument as the accounts show that £6-13sh-4d were paid “for ane pair of pypes to the piper”, then just to show that chanter accidents happened even then, in 1677 a further £1-15sh was paid “for ane chantrill to the pypers pypes”. Of course instruments have running costs and the following year 14 shillings was spent. Presumably as the animals tended to be smaller then, one skin was used for the bag while another was needed to provide the long strip of leather required to over-sew the welt.

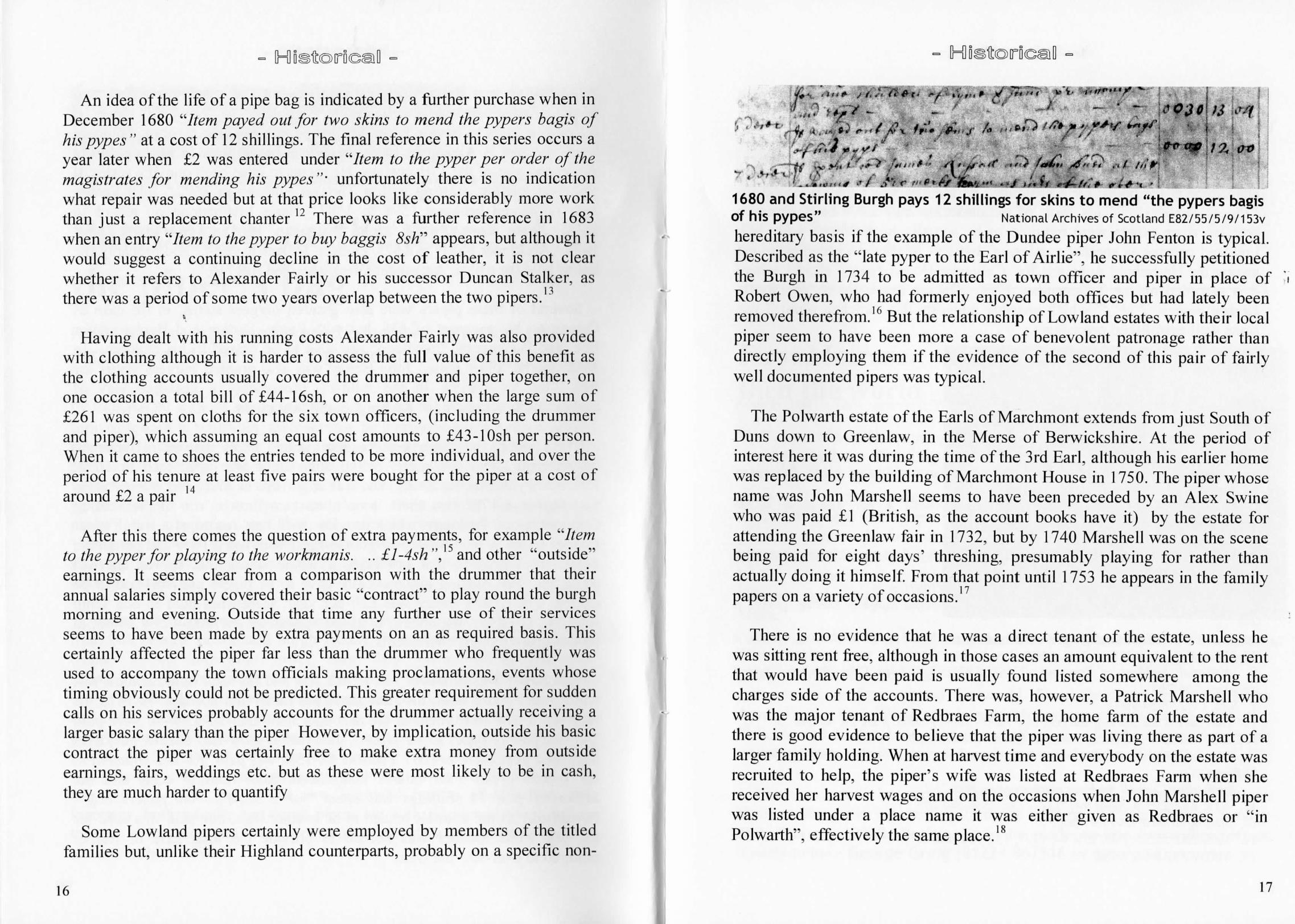

An idea of the life of a pipe bag is indicated by a further purchase when in December 1680 “Item payed out for two skins to mend the pypers bagis of his pypes” at a cost of 12 shillings. The final reference in this series occurs a year later when £2 was entered under “Item to the pyper per order of the magistrates for mending his pypes”. Unfortunately there is no indication what repair was needed but at that price looks like considerably more work than just a replacement chanter.(12) There was a further reference in 1683 when an entry “Item to the pyper to buy baggis 8sh” appears, but although it would suggest a continuing decline in the cost of leather, it is not clear whether it refers to Alexander Fairly or his successor Duncan Stalker, as there was a period of some two years overlap between the two pipers.(13)

Having dealt with his running costs Alexander Fairly was also provided with clothing although it is harder to assess the full value of this benefit as the clothing accounts usually covered the drummer and piper together, on one occasion a total bill of £44-16sh, or on another when the large sum of £261 was spent on clothes for the six town officers, (including the drummer and piper), which assuming an equal cost amounts to £43-10sh per person. When it came to shoes the entries tended to be more individual, and over the period

of his tenure at least five pairs were bought for the piper at a cost of around £2 a pair.(14)

After this there comes the question of extra payments, for example “Item to the pyper for playing to the workmanis.... £l-4sh ”, (15) and other “outside” earnings. It seems clear from a comparison with the drummer that their annual salaries simply covered their basic “contract” to play round the burgh morning and evening. Outside that time any further use of their services seems to have been made by extra payments on an as required basis. This certainly affected the piper far less than the drummer who frequently was used to accompany the town officials making proclamations, events whose timing obviously could not be predicted. This greater requirement for sudden calls on his services probably accounts for the drummer actually receiving a larger basic salary than the piper. However, by implication, outside his basic contract the piper was certainly free to make extra money from outside earnings, fairs, weddings etc. but as these were most likely to be in cash, they are much harder to quantify.

Some Lowland pipers certainly were employed by members of the titled families but, unlike their Highland counterparts, probably on a specific non-hereditary basis if the example of the Dundee piper John Fenton is typical. Described as the “late pyper to the Earl of Airlie”, he successfully petitioned the Burgh in 1734 to be admitted as town officer and piper in place of Robert Owen, who had formerly enjoyed both offices but had lately been removed therefrom.(16) But the relationship of Lowland estates with their local piper seem to have been more a case of benevolent patronage rather than directly employing them if the evidence of the second of this pair of fairly well documented pipers was typical.

The Polwarth estate of the Earls of Marchmont extends from just South of Duns down to Greenlaw, in the Merse of Berwickshire. At the period of interest here it was during the time of the 3rd Earl, although his earlier home was replaced by the building of Marchmont House in 1750. The piper whose name was John Marshell seems to have been preceded by an Alex Swine who was paid £1 (British, as the account books have it) by the estate for attending the Greenlaw fair in 1732, but by 1740 Marshell was on the scene being paid for eight days' threshing, presumably playing for rather than actually doing it himself. From that point until 1753 he appears in the family papers on a variety of occasions.(17)

There is no evidence that he was a direct tenant of the estate, unless he was sitting rent free, although in those cases an amount equivalent to the rent that would have been paid is usually found listed somewhere among the charges side of the accounts. There was, however, a Patrick Marshell who was the major tenant of Redbraes Farm, the home farm of the estate and there is good evidence to believe that the piper was living there as part of a

larger family holding. When at harvest time and everybody on the estate was recruited to help, the piper's wife was listed at Redbraes Farm when she received her harvest wages and on the occasions when John Marshell piper was listed under a place name it was either given as Redbraes or “in Polwarth”, effectively the same place.(18)

The mixture of records included both payments to the piper but also records of the piper buying oatmeal from the estate and also receiving a loan of money, which again points to him living locally.

On one occasion in 1747 he seems to have been required to be in attendance at the house for a prolonged period and was paid £l-2sh-6d for “Pipers Suppers” (19) This form of remuneration may have been common practice when pipers were required to be actually in residence with their Lowland patrons as another version of that sort of allowance can be found among the Household Accounts for Callendar House, (near Falkirk), where it is recorded on the 3 December 1759, “To my Lords pyper two weeks kitchen money, .2sh”(20) which possibly suggests that “kitchen piping” has some well established precedents.

References

- Beaton, E and MacIntyre, eds. The Burgesses of Inveraray 1665 1963, Scottish Record Society. New Series 14, (1990). p 178.

- Scottish History Society, 4th series, vol 17 Stirling Presbytery Records 1581-1587 p84

- Renwick, ed, Extracts from the Records of the Burgh of Stirling, p 118: Register of the Kirk Session of Stirling in Dennistoun, J and MacDonald, A, eds, Miscellany of the Maitland Club, vol i. (1833), p 131 132.

- Renwick, R, Extracts from the Records of the Royal Burgh of Stirling, (1889), p 136

- Harrison, J, Stirling Burgess List 1600 1699, (1991), p 29

- Renwick, R, Extracts from the Records of the Royal Burgh of Stirling. (1889), p 245

- Renwick, R, ed, Extracts from the Records of the Royal Burgh of Stirling, (1889), p 12- 13

- National Archives of Scotland, (NAS), E82/55/5/9, folio Stirling Council Archives B66/23/I

9) NAS, CC21/6/54/3604.

- Harrison, J, Stirling Burgess List 1600 1699, (1991), p 26, 29, 40 and 73.

- NAS, E82/55/5/9, Stirling Common Good Accounts 1660 1682. Some additional runs of accounts including some of the years from 1683 to 1690 can can be found in the Stirling Council Archives catalogued as B66/23/1

12) NAS, E82/55/5/9, folios 94v, 112, 113v, 153vand 169.

13) Stirling Archive B66/23/1 page 2.

14) NAS, E82/55/5/9J85, 91v, 94, 12Iv, 130, 152 and 157

15) NAS, E82/55/5/9,f95v.

16) Hay, T ed. Charters, writs and public documents of the Royal Burgh of Dundee, the hospital and Johnson's Bequest, 1292 1880, (1880), page 177 (The piper was actually instructed to use a hautboy in the morning and the bagpipe at night. Dundee clearly preferred a gentler awakening).

17) NAS, GD1/651/12, GD1/651/14

18) NAS, GD1/651/6, GD1/651/7 GD1/651/13

19) NAS, GD1/651/13

20 Calatria, number 3, Autumn 1992.