Johnny Lad - Pipe and Song

Pete Stewart explores the variety of songs with this title

Perhaps the most widely known song with this title is the one made famous by The Corries among others, which has the chorus line:

‘I’ll dance the buckles of my shoon wi’ you Johnny Lad”1

All I have to say about this song is that at least one old recorded version has ‘I’ll drink the buckles off my shoon’ 2 and to note that ‘buckles’ has been sung as '...Ah'll dance the bauchles aff ma feet ...'3

There is, however, what appears to be an earlier version, with a rather different tune: [this setting is from the Digital Tradition Folk Song Database at mudcat.org]

[These 4 bars are repeated for each 2 lines of the song and chorus. To avoid the high B, play bar 2.vii as E, bar 3.i as G' ]

O- ken ye my love Johnnie he’s doon on yonder lea,

An he’s lookin an’ he’s jukin’ an’ he’s aye teasin’ me,

He’s puin’ and’ he’s teasin’ but his meanin’s nae sae bad,

Gin it’s ever gaun tae be, tell me noo, Johnnie lad.

Tell me noo, my Johnnie laddie,

Tell me noo, my Johnnie lad,

Gin it’s ever gaun tae be,

tell me noo, Johnnie lad.

There is more about the history of this song and its relations at http://sangstories.webs.com/johnnielad.htm. Its later version, the ‘dance the buckles of my shoon’ one, became the sort of song that accumulates comic verses; Ewan McColl said of it “Johnny Lad moved to Glasgow during the late 19th century and was transformed into a children's street song. The lyrics became urbanized and the original air was abandoned in favor of a catchy but much plainer tune.”

But there is a much older song with t

he same title, the words of which were published by David Herd in 1769. 4

“XXVIII

Johny Lad

Hey how Johny Lad, ye’re no sae kind’s ye sud hae been,

Gin your voice I had na kent, I cou'd na eithly trow my een

Sae weel’s ye might hae tousled me, and sweetly pried my mow between,

Hey how Johny Lad, ye’re no sae kind’s ye sud hae been,

My father he was at the pleugh, mu mither she was at the mill

My billie he was at the moss, and no one near our sport to spill,

The fint a body was therein, ye need na flay’d for being seen,

Hey how Johny Lad, ye’re no sae kind’s ye sud hae been,

Wad ony lad wha lo'ed her weel, hae left his bonny lass her lane,

To sigh and greet ilk langsome hour, and think her sweetest minutes gane,

O, had ye been a wooer leal, we shu'd hae met wi' hearts mair keen,

Hey how my Johnie lad, ye 're no sae kind's ye sud hae been

But I maun hae anither joe, whase love gangs never out o’ mind

And winna let the mamens pass, whan to a lass he can be kind

Then gang yere wa’s to Blinking Bess, nae mair for Johny shal she green

Hey how Johny Lad, ye’re no sae kind’s ye sud hae been,.”

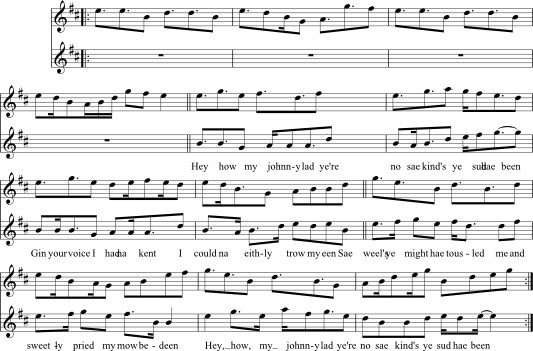

Here is the music published in the Scots Musical Museum with Herd’s words: [Vol. IV, Song 357. [I have lowered the first three notes of bars 5 & 7 by an octave]

Robert Tannahill later produced his own version, published in The Pocket Songster or Caledonian Warbler, 1823:5

OCH HEY, JOHNNIE LAD

Och hey, Johnnie lad,

Ye're no sae kind's ye should hae been

Och hey, Johnnie lad !

Ye didna keep your tryste yestreen. I waited lang beside the wood,

Sae wae an' weary a' my lane ;

Och hey, Johnnie lad !

It was a waefu' night yestreen.

I looked by the whinnie knowe,

I looked by the firs sae green,

I looked by the spunkie howe,

An aye I thought ye wad hae been.”

However, I first encountered this collection of tunes when playing ‘Johnny Lad’ as published by Matt Seattle in his ‘The Border Bagpipe Book’;6 in his notes Matt gives MacKenzie’s ‘The National Dance Music of Scotland’ [c.1840] as his source. Before I was aware of the Musical Museum setting, I attempted to set Herd’s words to this tune, which, with one or two minor adjustments, I was able to do. Here is my slightly amended version of Matt’s setting: [Matt describes his version as ‘with very minor alterations’; I have made some more, chiefly in the anacrusis.]

While working on this setting, I slowly came to realise that the tune was familiar as a song which I had known many years ago from a recording by Ray Fisher, titled ‘Johnny Sangster’, with the chorus:

“For you, Johnnie, you Johnnie, you, Johnnie Sangster,”

I'll trim the gavel o' my sheaf, For ye're the gallant bandster”

This song was probably written in Aberdeenshire by William Scott some time before 1850. It is usually sung in Strathpsey rhythm.7 Notes in the Greig-Duncan collection add that the “air to which Johnnie Sangster is sung is an old Strathspey tune known as Johnnie Lad”, which seems to imply that the tune had an independent existence prior to Scott’s song, and if that is so then it almost certainly had a different set of words. Whether these words were those in David Herd’s book is not likely to be easily decided. I therefore offer the following combination of Mackenzie’s tune with Herd’s words as possibly originating in the 18th century, or possibly in the 21st; the pipe setting, however, is assuredly 21st century.

Notes

1 Buchan, Peter, Ancient Ballads and Songs (1828)

2 Ord, John & Fenton, Alex., Ord’s Bothy Songs and Ballads, 1930

3 Jim McLean, http://www.mudcat.org/thread.cfm?threadid=7570

4 Additional verses were included in Herd’s notes; see http://preview.tinyurl.com/clp665z

5 http://preview.tinyurl.com/cshk4rh ; you can hear these words sung to the Muical Museum tune at http://preview.tinyurl.com/c7pc22y

6 Seattle, Matt, The Border Bagpipe Book, Dragonfly Music, 1994

‘I’ll dance the buckles of my shoon wi’ you Johnny Lad”1

All I have to say about this song is that at least one old recorded version has ‘I’ll drink the buckles off my shoon’ 2 and to note that ‘buckles’ has been sung as '...Ah'll dance the bauchles aff ma feet ...'3

There is, however, what appears to be an earlier version, with a rather different tune: [this setting is from the Digital Tradition Folk Song Database at mudcat.org]

[These 4 bars are repeated for each 2 lines of the song and chorus. To avoid the high B, play bar 2.vii as E, bar 3.i as G' ]

O- ken ye my love Johnnie he’s doon on yonder lea,

An he’s lookin an’ he’s jukin’ an’ he’s aye teasin’ me,

He’s puin’ and’ he’s teasin’ but his meanin’s nae sae bad,

Gin it’s ever gaun tae be, tell me noo, Johnnie lad.

Tell me noo, my Johnnie laddie,

Tell me noo, my Johnnie lad,

Gin it’s ever gaun tae be,

tell me noo, Johnnie lad.

There is more about the history of this song and its relations at http://sangstories.webs.com/johnnielad.htm. Its later version, the ‘dance the buckles of my shoon’ one, became the sort of song that accumulates comic verses; Ewan McColl said of it “Johnny Lad moved to Glasgow during the late 19th century and was transformed into a children's street song. The lyrics became urbanized and the original air was abandoned in favor of a catchy but much plainer tune.”

But there is a much older song with the same title, the words of which were published by David Herd in 1769. 4

“XXVIII

Johny Lad

Hey how Johny Lad, ye’re no sae kind’s ye sud hae been,

Gin your voice I had na kent, I cou'd na eithly trow my een

Sae weel’s ye might hae tousled me, and sweetly pried my mow between,

Hey how Johny Lad, ye’re no sae kind’s ye sud hae been,

My father he was at the pleugh, mu mither she was at the mill

My billie he was at the moss, and no one near our sport to spill,

The fint a body was therein, ye need na flay’d for being seen,

Hey how Johny Lad, ye’re no sae kind’s ye sud hae been,

Wad ony lad wha lo'ed her weel, hae left his bonny lass her lane,

To sigh and greet ilk langsome hour, and think her sweetest minutes gane,

O, had ye been a wooer leal, we shu'd hae met wi' hearts mair keen,

Hey how my Johnie lad, ye 're no sae kind's ye sud hae been

But I maun hae anither joe, whase love gangs never out o’ mind

And winna let the mamens pass, whan to a lass he can be kind

Then gang yere wa’s to Blinking Bess, nae mair for Johny shal she greenHey how Johny Lad, ye’re no sae kind’s ye sud hae been,.”

Here is the music published in the Scots Musical Museum with Herd’s words: [Vol. IV, Song 357. I have lowered the first three notes of bars 5 & 7 by an octave]

Robert Tannahill later produced his own version, published in The Pocket Songster or Caledonian Warbler, 1823:5

OCH HEY, JOHNNIE LAD

Och hey, Johnnie lad,

Ye're no sae kind's ye should hae been

Och hey, Johnnie lad !

Ye didna keep your tryste yestreen.

I waited lang beside the wood,

Sae wae an' weary a' my lane ;

Och hey, Johnnie lad !

It was a waefu' night yestreen.

I looked by the whinnie knowe,

I looked by the firs sae green,

I looked by the spunkie howe,

An aye I thought ye wad hae been.”

However, I first encountered this collection of tunes when playing ‘Johnny Lad’ as published by Matt Seattle in his ‘The Border Bagpipe Book’;6 in his notes Matt gives MacKenzie’s ‘The National Dance Music of Scotland’ [c.1840] as his source. Before I was aware of the Musical Museum setting, I attempted to set Herd’s words to this tune, which, with one or two minor adjustments, I was able to do. Here is my slightly amended version of Matt’s setting: [Matt describes his version as ‘with very minor alterations’; I have made some more, chiefly in the anacrusis.]

While working on this setting, I slowly came to realise that the tune was familiar as a song which I had known many years ago from a recording by Ray Fisher, titled ‘Johnny Sangster’, with the chorus:

“For you, Johnnie, you Johnnie, you, Johnnie Sangster,”

I'll trim the gavel o' my sheaf, For ye're the gallant bandster”

This song was probably written in Aberdeenshire by William Scott some time before 1850. It is usually sung in Strathpsey rhythm.7 Notes in the Greig-Duncan collection add that the “air to which Johnnie Sangster is sung is an old Strathspey tune known as Johnnie Lad”, which seems to imply that the tune had an independent existence prior to Scott’s song, and if that is so then it almost certainly had a different set of words. Whether these words were those in David Herd’s book is not likely to be easily decided. I therefore offer the following combination of Mackenzie’s tune with Herd’s words as possibly originating in the 18th century, or possibly in the 21st; the pipe setting, however, is assuredly 21st century.

Notes