Who Paid The Pipers

IAIN MacINNES (pictured) discusses the chequered history of patronage in Highland, Lowland and Union piping

ROYALTY. A rare commodity, but ~ if history is anything to go by - one not to be done without in piping circles. For royalty, of course, you should really read patronage. As patrons go, kings and queens are best; princes and dukes are pretty fine; and a good old-fashioned, blue-blooded aristocrat can make a very nice substitute.

It's probably fair to say that the 1780s to the 1850s were the purple years of piping patronage - years which witnessed the divergent fortunes of the Highland pipe, the union pipe, and the Lowland bellows pipe. While the Highland and union instruments went from strength to strength, the Scottish Lowland tradition gradually faded, to show tentative rebirth only in the last decade or so. In the following pages comparisons are made between the three instruments, particularly with respect to the degree of patronage from rich and influential sources enjoyed by each. Patronage, of course, wasn’t everything - but it certainly helped.

HIGHLAND PIPES: When we talk of aristocratic patronage, we probably think of the Highland pipes, adopted by the Scottish nobility and armed forces in the 1780s and subsequently spread to the corners of the British Empire.

For an instrument of relatively humble origins, this was quite an achievement. It did, of course, have the advantage of some antiquity, and a certain degree of standing in the clan courts of old. Its chief practitioners (MacCrimmons, MacArthurs et al.) were men of minor landowning status (latterly tacksmen), rather than mere tenants. They attracted students to their homes, and at meetings performed both dance music and a music of a more esoteric and elevated nature, ceol mor, which drew inspiration from the cadences and rhythms of Gaelic song and speech, and from the complexities of oran mor .

The pedigree, therefore, was good, and although the instrument must have suffered somewhat in the wake of the 1746 Disarming Act, it was to enjoy quite unprecedented popularity from the 1780s to the mid-1820s. The British nation was then gripped by war-fever, and it was discovered that the Highland pipe could quite genuinely raise the spirits and fire the courage of Scottish soldiers, often fighting under very unpleasant circumstances. At home a public relations exercise was mounted to attract pipers to the army, chiefly through the medium of a lucrative annual competition held in Edinburgh, Sponsored by the Highland Society of London. Reports of a suitable inflammatory nature were carried by the press: ..."what could be more gallant or heroic than a man unarmed advancing intrepidly in the face of an enemy, encouraging his comrades to deeds of hardihood and glory, by those martial strains so congenial and animating to the feelings of every Highlander?"(1)

Meanwhile, in the drawing rooms of Edinburgh, the instrument's potency was further lauded in the literary outpourings of the Romantics ~ lucid, and frequently fantastic. Their mood was in all ways conducive to the spread and development of the Highland pipe.

Wealthy landowners discovered that they could emulate the "old order" simply by employing a piper to work on the estate. Highland Society members, feeling that they should do something to support the Noble Instrument, lent their names as subscribers to the growing number of pipe music collections (2). And when George IV was greeted by the pipes at Leith Pier in 1822, royal approval was sealed.

The momentum generated was sufficient to carry the instrument in a healthy state to the present day. The music repertory has been expanding constantly; most pipers are reasonably literate in pipe music and some actually make a living from the instrument. If there has been a price to pay ~ well, perhaps we see it in the dilution of the potent brew of ceol mor somewhere on the long road south, or in the ocean miles between Raasay and the New World.

UNION PIPES: In certain ways a more impressive achievement was that of the union pipe, which in the mid-18th century was essentially a new instrument, and could day no claim either to antiquity or martial prowess. Its evolution took a very different course from that of the Highland pipe, but did nevertheless benefit enormously from the activities of gentlemen practitioners and patrons, while enjoying popular support not only in Ireland, but also in England and Lowland Scotland.

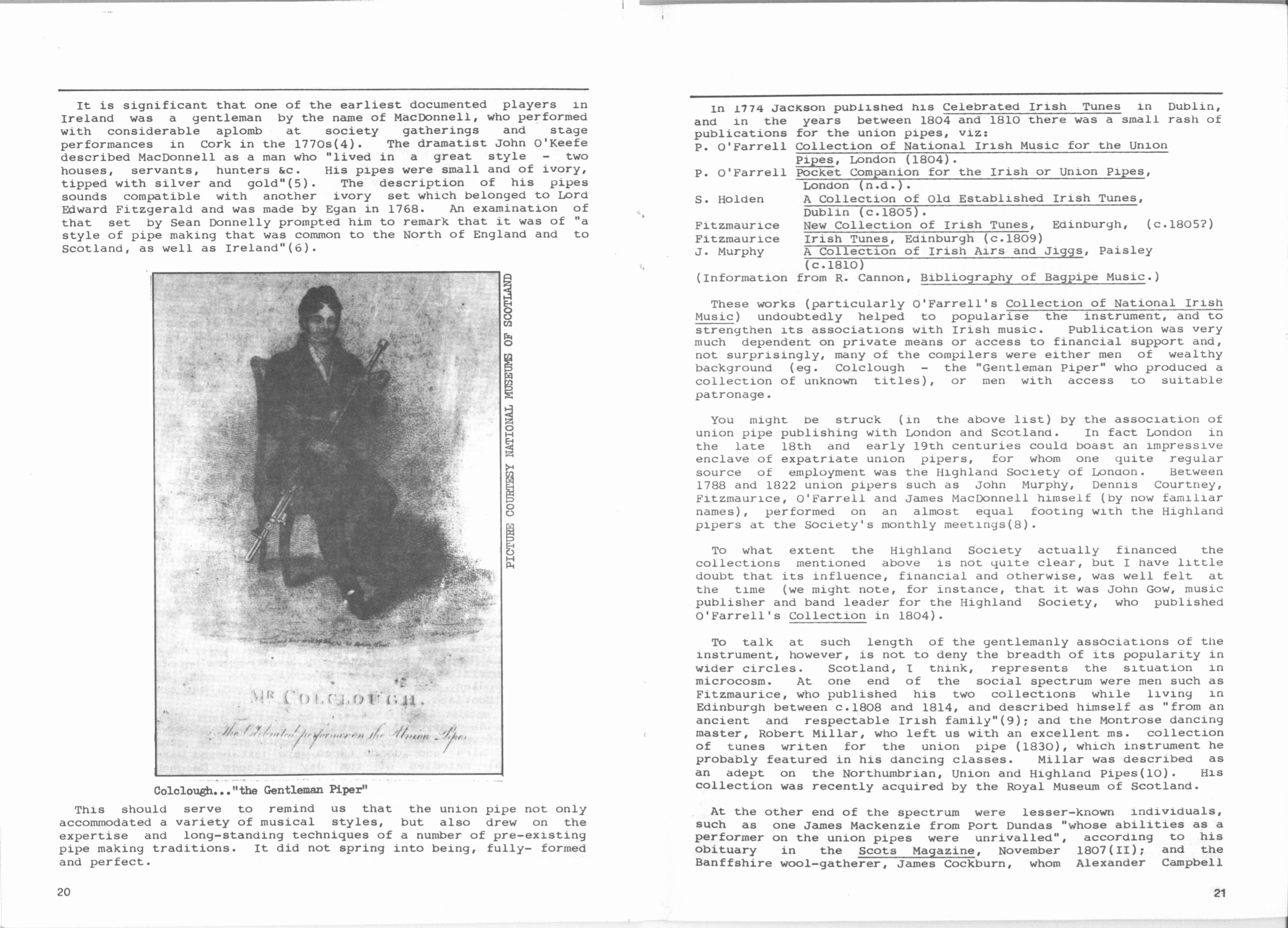

With pleasant tone, and versatility, the union pipe was soon being practiced, often skilfully, in the parlours of the gentry. There, traditional airs and dance tunes were juxtaposed with the popular and classical melodies of the day (witness Geoghegan's Tutor, produced in London in 1746, which contained tunes almost exclusively of the latter type), and it could be plausibly argued that the instrument's relatively swift and ingenious development was prompted by the demands of such varied repertoire. It soon found favour with stage audiences; note, for instance, its well-publicised role in the opera Oscar and Malvina, played at Covent Garden in 1798, with one Dennis Courtney on pipes (3), and occasionally thereafter. It is significant that one of the earliest documented players in Ireland was a gentleman by the name of MacDonnell, who performed with considerable aplomb at society gatherings and stage performances in Cork in the 1770s (4). The dramatist John O'Keefe described MacDonnell as a man who "lived in a great style - two houses, servants, hunters & c. His pipes were small and of ivory, tipped with silver and gold" (5). The description of his pipes sounds compatible with another ivory set which belonged to Lord Edward Fitzgerald and was made by Egan in 1768. An examination of that set by Sean Donnelly prompted him to remark that it was of "a style of pipe making that was common to the North of England and to Scotland, as well as Ireland"(6).

This should serve to remind us that the union pipe not only accommodated a variety of musical styles, but also drew on the expertise and long-standing techniques of a number of pre-existing pipe making traditions. It did not spring into being, fully- formed and perfect.

In 1774 Jackson published his Celebrated Irish Tunes in Dublin, and in the years between 1804 and 1810 there was a small rash of publications for the union pipes, viz:

P. O'Farrell Collection of National Irish Music for the Union Pipes, London (1804).

P. O'Farrell Pocket Companion for the Irish or Union Pipes, London (n.d.).

S. Holden A Collection of Old Established Irish Tunes, Dublin (c.1805).

Fitzmaurice New Collection of Irish Tunes, Edinburgh, (c.1805?)

Fitzmaurice Irish Tunes, Edinburgh (c.1809)

J. Murphy A Collection of Irish Airs and Jiggs, Paisley (c.1810)

(Information from R. Cannon, Bibliography of Bagpipe Music.)

These works (particularly O'Farrell's Collection of National Irish Music) undoubtedly helped to popularise the instrument, and to strengthen its associations with Irish music. Publication was very much dependent on private means or access to financial support and, not surprisingly, many of the compilers were either men of wealthy background (eg. Colclough - the "Gentleman Piper" who produced a collection of unknown titles), or men with access to suitable patronage.

You might be struck (in the above list) by the association of union pipe publishing with London and Scotland. In fact London in the late 18th and early 19th centuries could boast an impressive enclave of expatriate union pipers, for whom one quite regular source of employment was the Highland Society of London. Between 1788 and 1822 union pipers such as John Murphy, Dennis’ Courtney, Fitzmaurice, O'Farrell and James MacDonnell himself (by now familiar names), performed on an almost equal footing with the Highland

Pipers at the Society's monthly meetings (8).

To what extent the Highland Society actually financed the collections mentioned above is not quite clear, but I have little doubt that its influence, financial and otherwise, was well felt at the time (we might note, for instance, that it was John Gow, music publisher and band leader for the Highland Society, who published O'Farrell's Collection in 1804).

To talk at such length of the gentlemanly associations of the instrument, however, is not to deny the breadth of its popularity in wider circles. Scotland, I think, represents the situation in microcosm. At one end of the social spectrum were men such as Fitzmaurice, who published his two collections while living in Edinburgh between c.1808 and 1814, and described himself as "from an ancient and respectable Irish family" (9); and the Montrose dancing master, Robert Millar, who left us with an excellent ms. collection of tunes writen for the union pipe (1830), which instrument he probably featured in his dancing classes. Millar was described as an adept on the Northumbrian, Union and Highland Pipes (10). His collection was recently acquired by the Royal Museum of Scotland.

At the other end of the spectrum were lesser-known individuals, such as one James Mackenzie from Port Dundas "whose abilities as a performer on the union pipes were unrivalled", according to his obituary in the Scots Magazine, November 1807(II); and the Banffshire wool-gatherer, James Cockburn, whom Alexander Campbell heard play on the Irish Pipes in 1816, albeit indifferently"(12).

Men of all backgrounds playing all sorts of music. The union pipe was, and remains, a most versatile instrument, supported in the broadest of circles.

LOWLAND PIPES: Where the late 18th and early 19th centuries saw the Highland and union pipes in the pink of health, the Lowland bellows pipe faded slowly, and largely unnoticed, from the scene. A comparison between the 1778 and 1853 editions of the Encyclopedia Britannica, published in Edinburgh, makes the point rather poignantly. The 1778 edition describes both the "Scots Lowland pipe" and the "small pipe" (in reality a Northumbrian pipe), and tells the curious tale of George Mackie, who, while studying in Skye “adapted the graces of the highland music to the Lowland pipe". Ominously, the account proceeds: "Upon his return [Mackie] was heard with astonishment and admiration; but unluckily, not being able to commit his improvements to writing, and indeed, the nature of the instrument scarce admitting of it, the knowledge of this kind of music hath continued to decay ever since, and will probably soon wear out altogether."

In 1853 the Encyclopedia stated: "Sixty years ago, several kinds of bagpipe were used in Scotland and the North of England; but now we seldom hear any others than the small Irish bagpipe, blown with bellows, and the great Highland bagpipe...."

Hence the Lowland pipe was gone. Before attempting to pinpoint some causes of this untimely passing, allow me to conduct a lightning tour over certain aspects of the history of the instrument (for how can we consign the corpse to the grave without first singing its praises?)

Town Pipers: For simplicity, it is worthwhile distinguishing between the town pipers, who were municipal employees; itinerant pipers, who followed the seasons and harvests, and busked for their dinner; and those who simply birled away for their own pleasure.

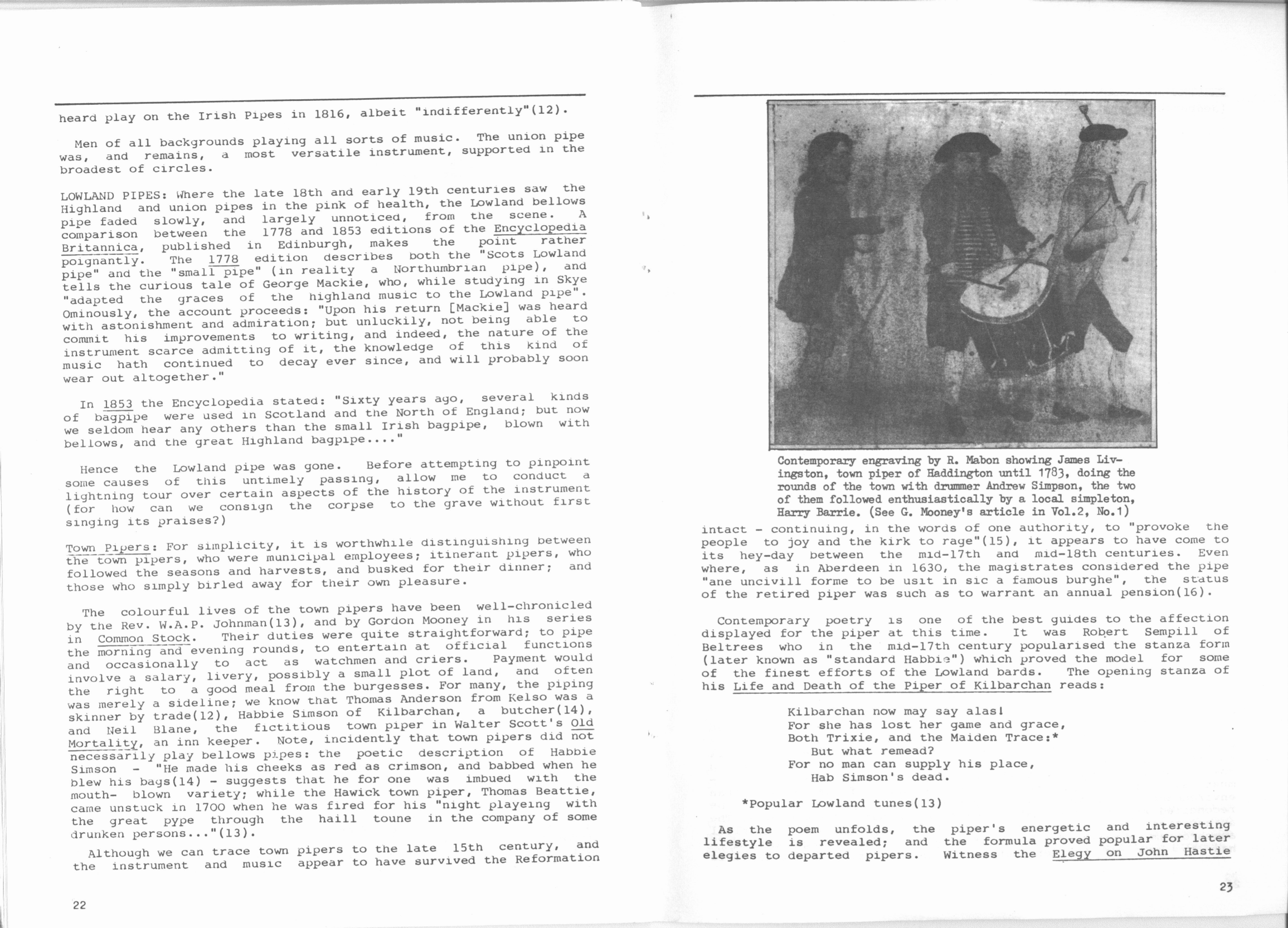

The colourful lives of the town pipers have been well-chronicled by the Rev. W.A.P. Johnman (13), and by Gordon Mooney in his series in Common Stock. Their duties were quite straightforward; to pipe the morning and evening rounds, to entertain at official functions and occasionally to act as watchmen and criers. Payment would involve a salary, livery, possibly a small plot of land, and often the right to a good meal from the burgesses. For many, the piping was merely a sideline; we know that Thomas Anderson from Kelso was a skinner by trade(12), Habbie Simson of Kilbarchan, a butcher(14), and Neil Blane, the fictitious town piper in Walter Scott's Old Mortality, an inn keeper. Note, incidently, that town pipers did not necessarily play bellows pipes: the poetic description of Habbie Simson - "He made his cheeks as red as crimson, and babbed when he blew his bags(14) - suggests that he for one was imbued with the mouth-blown variety; while the Hawick town piper, Thomas Beattie, came unstuck in 1700 when he was fired for his "night playeing with the great pype through the haill toune in the company of some drunken persons..."(13).

Although we can trace town pipers to the late 15th century, and the instrument and music appear to have survived the Reformation intact - continuing, in the words of one authority, to "provoke the people to joy and the kirk to rage"(15), it appears to have come to its hey-day between the mid-17th and mid-18th centuries. Even where, as in Aberdeen in 1630, the magistrates considered the pipe “ane uncivill forme to be usit in sic a famous burghe", the status of the retired piper was such as to warrant an annual pension(16).

Contemporary engraving by R. Mabon showing James Livingston, town piper of Haddington until 1783, doing the rounds of the town with drummer Andrew Simpson, the two of them followed enthusiastically by a local simpleton, Harry Barrie. (See G. Mooney's article in Vol.2, No.1)

Contemporary poetry is one of the best guides to the affection displayed for the piper at this time. It was Robert Sempill of Beltrees who in the mid-17th century popularised the stanza form (later known as “standard Habbie") which proved the model for some of the finest efforts of the Lowland bards. The opening stanza of his Life and Death of the Piper of Kilbarchan reads:

Kilbarchan now may say alas!

For she has lost her game and grace,

Both Trixie, and the Maiden Trace:*

But what remead?

For no man can supply his place,

Hab Simson's dead.

*popular Lowland tunes(13)

As the poem unfolds, the piper's energetic and interesting lifestyle is revealed; and the formula proved popular for later elegies to departed pipers. Witness the Elegy on John Hastie (Jedburgh town piper in the early 18th century):

But we his mem'ry deal shall mind,

While billows rair, or blows the wind;

To tak’ him hence Death was no king-

O dismal feed:

We'll never sic anither find,

Since Johnie's dead.(13)

Itinerants: The second category of Lowland piper, itinerants such as Gypsies and Travellers, and seasonal labourers following the harvests, rarely enjoyed such popular esteem and certainly could not boast the luxury of municipal employment. Indeed, during outbreaks of illness they were positively shunned by the towns, as demonstrated in the following undated statute cited by Johnman:

"it is statute and ordainit that na pyperis, fidleris, menstrales, or ony other vagabondis, remain in the town fra this tyme furtht during the tyme of the pest...under the paine of scurgeyng and banishment."(13)

Pickings must at times have been pretty lean for these men, although undoubtedly their piping was only one of many skills adapted to the travelling life. Walter Scott(17) and John Leyden(18) saw them as bearers of a unique body of lore and music, much of which was to die with them, One quasi-humorous account of the famous Northumbrian traveller, John Allan, might help to illustrate the lifestyle (and pitfalls) experienced by such men. The scene is a Kelso pub in the late 18th century. John Allan has played his pipes:

"The Company were delighted with his music, and the musician was equally pleased with the hearty manners of his hearers. He therefore not only played, but also danced, sang, told droll stories, and acted the mimic, so as to become a great attraction to the house. On the second evening, and while in the hey-day of his merriment, he agreed to sleep at the lodgings of a handsome seducing female; but in the morning he found, to his great mortification, that both his money and his fair friend had disappeared."(19)

In a similar vein, James Hogg tells a (supposedly true) story of a Gypsy piper who had the misfortune to be fatally stabbed, in a quarrel over a lady, while passing through Ettrick. This prompted the observation: God forbid that every amorous minstrel should be so sharply taken to task these days"1(20)

End of a tradition: Sadly, by the late 18th century, as demonstrated in the Encyclopedia Britannica, the fortunes of the Lowland pipe were on the wane. Socio-economic, as much as specifically cultural changes, lay behind this. The industrialisation of the Lowland towns, the declining status of the burghs, agricultural reforms—must all have contributed to the reshaping of the Lowland urban environment. How could the daily round of the pipe and drum be reconciled with the needs of the expanding manufacturing centre? The authorities - recognising the town piper as a historical anachronism, a relic of the age of burgh plot and village market -had to look no further than the burgh records, packed with lurid details of piper's transgressions, to justify the end of such outmoded employment. The pipers, indeed, had done themselves no favours in their occasional lapses of discipline: witness the instructions to the Glasgow town pipers (of uncertain date) which found it necessary to warn them "to leiff af thair extaordiner drinking sua that thai may pass honestlie throw the towne in their service, nor to leiff thair playing in ganging off the calsaye ether to masones or drinking."(13)

And with declining official status, there came public condemnation. Where once the people of Perth are said to have found the piper's morning round “inexpressibly soothing and delightful"(21), the Dalkeith folk in the early 1800s clearly found the efforts of their piper, Robert Lorimer, quite unbearable. With the irony of the disaffected they castigated his music in verse: the measure - what else ~ was “standard Habbie":

O Lorimer! thou wicked wag,

I wish thee, and thy dinsome bag

Were twal feet 'neath a black peat—bag

Wet as the Severn,

Or pipin' to the Laird o' Lag

In Belzie's Cavern.

Ee'r daylight peeps within my chaumer

Is heard thy vile unearthly clamour,

Waukes the gude wife-the young anes yammer

Wi' ceaseless din;

I seize my breeks, an' outward stammer

Compell'd to rin.(13)

Chances of survival? The popular success of instruments such as the union pipe, fiddle, and Highland pipe in the early 19th century, may have hastened the departure of the Lowland Pipe, for lavish patronage of the one left little in the coffers for the other.

The Lowland pipe was essentially unable to compete. Musically it had been superseded by fiddles, melodeons, keyed pipes, and other instruments capable of large and varied repertoires to suit all occasions. John Leyden positively stated in 1801: “The fiddill...has, in the Scottish Lowlands, nearly supplanted the bagpipe"(18). Attempts were made to extend the scale - but these were ill-advised. The Encyclopedia Britannica observed in 1778 that "bagpipers, not content with the natural nine notes which their instrument can play easily, force it to play tunes requiring higher notes, which disorders the whole instrument in such a manner as to produce the most horrid discords; and this practice brings, though undeservedly, the instrument itself into contempt.” (Note how closely this concurs with Joseph MacDonald's belief that “this insipid imitation of other music is what gives such a contemptible notion of a pipe, because it must come so short of it...") (c.1760- 22).

Hence, where the union pipe gained credibility anda popularity through its versatile performance on the stage, the Lowland pipe had no such exposure. Where the Highland pipe achieved renown on the battlefield, the Lowland pipe could boast no such military prowess.

Where the Highland piper strutted manfully at the laird's table, decked in rich clothing and ornament, the Lowland piper could boast neither the clothing, nor the laird. (We should remember that the Lowland piper had traditionally been associated with the burgh rather than the estate, although there were cases of the laird Supporting a town piper, as with the Earl of Eaglinton in Eaglesham in 1772.) (23)

The Highland Societies of London and Scotland (prominent patrons of both Highland and upion pipes) certainly showed little interest in Lowland piping. In 1808 they did make a small donation to "a blind boy of interesting physiognomy" who was discovered roaming the streets of Edinburgh, trying to make a living from playing the bellows pipe(8); but the Lowland Piper who in 1819 had the temerity to enter the Highland piping competition in Edinburgh was quite forcibly advised that his presence was not required.

Sadly, two important influences on the Spread of Highland and union piping - competitions, and publications specifically catering for the instrument - were absent from the Lowland Piping tradition. The lack of publishing in this case was merely a further symptom of the dearth of patronage. Note that where the fiddle and Highland pipe collections of this era were festooned with tunes dedicated to the nobility and their offspring (for such was the price of patronage), the surviving Lowland pipe repertoirs, preserved in collections such as Robert Bremner's Scotch, Galwegian and Border Airs (1974), contained little music of this type. In fact, the old Lowland tunes were primarily concerned with matters of everyday life (i.e. The Stool of Repentance, Woo'd and Married and A'), which possibly goes to show that the true patrons of this instrument were quite simply the everyday folk.

The conclusion or, if you like, the moral of this story, is that patronage has played an important part in the varied fortunes of the three instruments discussed. The lesson is there to be learned: perhaps the present generation of Lowland pipers should be out currying favour with the current crop of munificent patrons (armed of course with suitable compositions of salutation and welcome.) But such has not been the way of the Lowland pipe. Rather better, I would say, to follow the example of a wandering Piper who in 1838 reached the verdant banks of the Clyde.

“this "celebrated individual", wrote the Caledonian Mercury, “Has again visited Glasgow, and was on Saturday last performing at Lauriston, Gorbals &c. Whatever may truly be his object he collects abundance of money, and is quite gentlemanly in his expenditure. On an old woman in apparently poor circumstances, presenting him with a 'bawbee' he told her that he thought she stood more in need of money than he did, and presented her with half a sovereign, to the great admiration of a large crowd." (24)

Surely when the piper pays, he can call his own tune?

BIBLIOGRAPHY AND NOTES

1. Caledonian Mercury Aug. 3 1816.

2. e.g. Donald MacDonald's Collection ¢c. 1819 and Angus MacKay's Collection 1835. etc.

3. J.G. Dalyell Musical Memoirs of Scotland. Edinburgh (1841) p.39. 4. Nicholas Carolan “McDonnell’s Uilleann Pipes" Ceol VI, 2, April 1984, p.60.

5. The Recollections of John O'Keefe London (1826), Vol.I, 9.246-7.

6. Sean Donnelly "Lord Eaward Fitzgerald's Pipes" Ceol vI, I, April 1983, p.7.

7. R.D. Cannon A Bibliography of Bagpipe Music Edinburgh (1980) p.94.

8. Highland Society of London Recerds. Nat. Lib. of Scotland Acc. 268.

9. Caledonian Mercury July 16 1808.

10. Edinburgh Evening Courant Feb.4 1836.

11. Scots Magazine, Nov. 1807, p.877.

12. Alexander Campbell Notes of my Third Journey to the Borders Edinb. Uni. Library/Laing div. Ti7 No. 378.

13. Rev. W.A.P. Johnman "Border Pipes and Pipers" Transactions of the Hawick Archaeological Society / Oct+Nov. 1913 / p.47=-56.

14. James Patterson The Poems of the Sempills of Beltrees Edinp.1849 p.41/p.93.

15. H.G. Farmer A History of Music in Scotland London 1947 j».132. 16. Quoted from Burgh Records in J. Maidment Analecta Scotica Edinb. 1834/II/ p.326.

17. Walter Scott Minstrelsy of the Scottish Border Edinb. (1902 Edn.) p.165-6.

18. John Leyden introduction to The Complaynt of Scotland Edinb. 1801/ pp-150-158.

19. James Thompson A New, Improved and Authentic Life of James Allan, Newcastle 1828, p.66-

20. James Hogg quoted in Thomson (ibid.) p.69.

21. James Logan The Scottish Gael II/ p. 286, London 1831.

22. Joseph MacDonald A Compleat Theory of the Scots Highland Bagpipe c.1760. Original Ms. in E.U.L. (La II1.804).

23. Celtic Monthly Vol.13, p.235.

24. Caledonian Mercury Aug.11 1938.