IN CONVERSATION WITH HAMISH MOORE

Hamish, you built up an international reputation as a performer, but you've not been piping for a number of years now. Would you be prepared to tell us something about this?

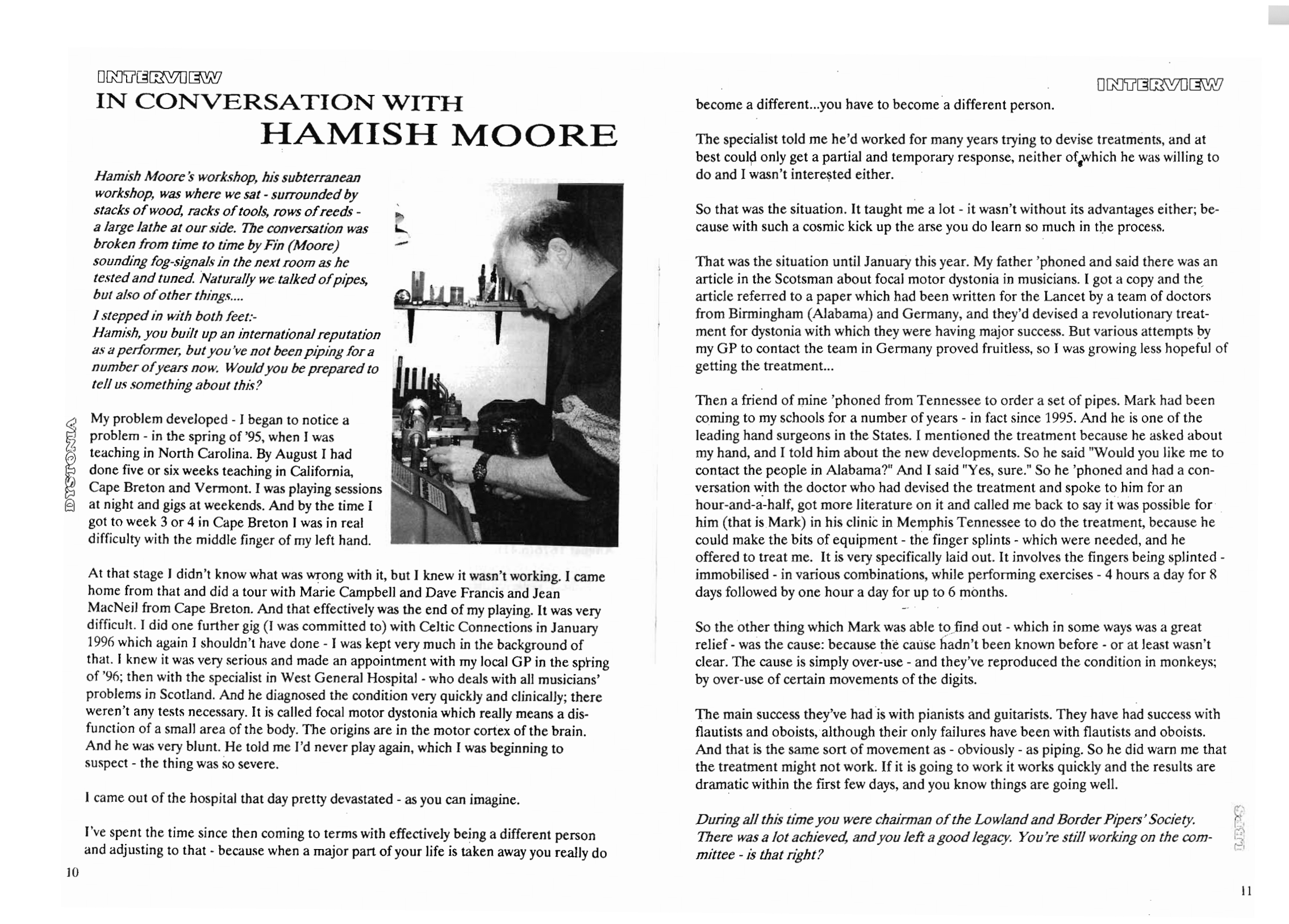

My problem developed - I began to notice a problem - in the spring of 95, when I was teaching in North Carolina. By August I had done five or six weeks teaching in California, Cape Breton and Vermont. I was playing sessions at night and gigs at weekends. And by the time I got to week 3 or 4 in Cape Breton I was in real difficulty with the middle finger of my left hand.

At that stage I didn’t know what was wrong with it, but I knew it wasn’t working. I came home from that and did a tour with Marie Campbell and Dave Francis and Jean MacNeil from Cape Breton. And that effectively was the end of my playing. It was very difficult. I did one further gig (I was committed to) with Celtic Connections in January 1996 which again I shouldn’t have done - I was kept very much in the background of that. I knew it was very serious and made an appointment with my local GP in the spring of ’96; then with the specialist in West General Hospital - who deals with all musicians’ problems in Scotland. And he diagnosed the condition very quickly and clinically; there weren't any tests necessary. It is called focal motor dystonia which really means a disfunction of a small area of the body. The origins are in the motor cortex of the brain. And he was very blunt. He told me I’d never play again, which I was beginning to suspect - the thing was so severe.

I came out of the hospital that day pretty devastated - as you can imagine.

I've spent the time since then coming to terms with effectively being a different person and adjusting to that - because when a major part of your life is taken away you really do become a different.,..you have to become a different person.

The specialist told me he’d worked for many years trying to devise treatments, and at best could only get a partial and temporary response, neither of which he was willing to do and I wasn’t interested either.

So that was the situation. It taught me a lot - it wasn’t without its advantages either; because with such a cosmic kick up the arse you do learn so much in the process.

That was the situation until January this year. My father ‘phoned and said there was an article in the Scotsman about focal motor dystonia in musicians. I got a copy and the article referred to a paper which had been written for the Lancet by a team of doctors from Birmingham (Alabama) and Germany, and they’d devised a revolutionary treatment for dystonia with which they were having major success. But various attempts by my GP to contact the team in Germany proved fruitless, so I was growing less hopeful of getting the treatment...

Then a friend of mine ‘phoned from Tennessee to order a set of pipes. Mark had been coming to my schools for a number of years - in fact since 1995. And he is one of the leading hand surgeons in the States. [ mentioned the treatment because he asked about my hand, and I told him about the new developments. So he said “Would you like me to contact the people in Alabama?” And I said “Yes, sure.” So he ‘phoned and had a conversation with the doctor who had devised the treatment and spoke to him for an hour-and-a-half, got more literature on it and called me back to say it was possible for him (that is Mark) in his clinic in Memphis Tennessee to do the treatment, because he could make the bits of equipment - the finger splints - which were needed, and he offered to treat me. It is very specifically laid out. It involves the fingers being splinted - immobilised - in various combinations, while performing exercises - 4 hours a day for 8 days followed by one hour a day for up to 6 months.

So the other thing which Mark was able to find out - which in some ways was a great relief - was the cause: because the cause hadn’t been known before - or at least wasn’t clear. The cause is simply over-use - and they’ve reproduced the condition in monkeys; by over-use of certain movements of the digits.

The main success they’ve had is with pianists and guitarists. They have had success with flautists and oboists, although their only failures have been with flautists and oboists. And that is the same sort of movement as - obviously - as piping. So he did warn me that the treatment might not work. If it is going to work it works quickly and the results are dramatic within the first few days, and you know things are going well.

During all this time you were chairman of the Lowland and Border Pipers’ Society. There was a lot achieved, and you left a good legacy. You're still working on the committee - is that right?

Well no. I’ve actually retired now. I did a year on the committee after I retired as Chairman, and have lapsed from that as well. Although I don’t discount going back onto the committee in the future at some stage. I would enjoy doing that - but I need a break.

Yes - you were heavily involved; for how long?

Three years - a little more; three and a half.

You obviously enjoyed your time as Chairman.

Oh yes; very much. And the committee were incredibly supportive. I was asking them to do a lot - and a lot of stuff which wasn’t proven. We didn’t know if it was going to work. We could have ended up very financially embarrassed. But they were very supportive, and I couldn’t have done it without them. I can’t emphasise that enough.

Now about pipes: we talked earlier about smallpipes going out of “true” a little bit as the wood settles down over a period of time. You keep the wood - a year or even more - ready bored before taking it down on the outside?

No. We rough turn them first, then leave them a year before boring - because if the wood bends, and you have already bored it, you’ve got a bent hole. And that’s OK if you're making something like a flute where your pilot is much smaller than your eventual bore. But these instruments are very small bored, so that even if you pilot out something smaller than the eventual bore, the tool will tend to follow the bend in the wood. That’s why we have to leave the wood un-bored for a year to let it dry and bend and then put the pilot up.

Later on, of course, you profile the outside. Looking at various smallpipe chanters I notice some of them are thick and some of them are thin, yet all have more or less the same internal dimensions. What effect does this have on the tone of the instrument - between a thick wall and thin wall?

I’m not sure, Jock. I don’t know accurately enough. It is tempting to say that the thin walled chanters vibrate better, but I don’t know that they do. To a large extent the thickness - and this is a terrible thing to admit - is determined by how much the wood moves. If it does you have to skim a 16th off and then if it moves again you have to skim another 16th off. You either end up with a thinner chanter or you waste that bit of wood which has cost quite a bit by that stage.

But the profiles we have adopted are all copied from existing sets - the smallpipes from an early 19th century bellows-blown set in Inverness-shire; the Border pipes from Cox’s plans

c.1740-60; the reel pipes from an 18th century set now in the Piping Centre; and the Highland pipes from the Black set of Kintail dated 1785.

If I understood you correctly from our earlier chat, Blackwood and Ebony are probably the most stable in this respect, and Boxwood least stable?

Yes. Boxwood is very prone to bending, and in fact we have a complex system of microwaving which allows the wood to bend. It’s a stress relieving process. And once that has occurred we then re-true it, and it tends not to bend anymore. We can't guarantee it, but we cut out probably 80-90% of the bending.

And of course you have different climates, which will have different effects as the player himself uses his pipes.

Yes. The worst problem is sending the pipes from our fairly humid climate here to a very dry climate. I find if the pipes are subjected to relative humidity of less than 40%, then there are problems.

Are these on-going problems?

No, they sort themselves out in the Spring, once the humidity goes up again. So anyone who wants to keep their pipes in playing order through the winter - and it's not just the Northeast corner of the States, it’s also Midwest and Canada: they have to humidify the pipes properly. And there are various methods of doing this, which I go into in some detail with the customer.

How does this show in the pipes - when they are drying out? What does the piper himself detect?

The wood shrinks, and the ferrules can loosen and the wood can bend a bit. The biggest effect is on the reeds - especially the chanter reed. And because it is such a small delicate item, and it’s responsible for the sound, when it moves and shifts there are major problems with the sound. What tends to happen first are leaks along the edges, and so you get squeaking when you play.

We were talking about Ebony and Blackwood being more stable than Boxwood. What other woods do you use?

The principal ones for smallpipes are Ebony and Blackwood. For my Border pipes I use Boxwood. We use Boxwood also for smallpipes in ‘D’ and ‘C’ principally, though we do use it in ‘A’ as well. And we use Yew as well for Border pipes - and we have recently added another item to the list, and that is Reel pipes, of which there is a very fine example in the piping centre in Glasgow, which we measured up recently. They are very similar to Border pipes but they were made by Highland pipe makers and played by Highland pipers. And I’m going to make those in Yew.

Why Yew?

It’s a beautiful looking wood. It’s less dense than boxwood. We've got a whole tree which has been seasoning for twelve years, so we've got plenty of material. And I think that when people are turning to the conical bore bellows blown pipes they are looking for an alternative to Highland pipes, and in my experience want something that is fairly quiet - in fact quiet as possible. So if I use a less dense timber I have more chance of achieving this.

Do you find you have to do any adjustments of finger hole spacings for the different types of wood? I think in the past we talked about this, and came to the conclusion that different woods sometimes had different effects on the tuning.

Yes, we do - I have a customer from the other side of Pitlochry who wanted a set made from a tree that was growing in Perthshire. We managed to get a Laburnum that was growing in Glen Farg, and for that we had to adjust the finger hole spacing on the chanter - because Laburnum is very low density compared with other woods.

As far as the mounts are concerned, what do you use; what do you favour?

Well we use two woods for the mounts; Boxwood and Cocobolo. I never use artificial ivory, and I’ve never used real ivory. I just like the appearance of these hardwoods. And obviously the customers like it. For the ferrules I am now using solid silver or gold-plated brass - as standard. All the silver is hallmarked at the Edinburgh Assay Office, and the brass is hallmarked with my own initials before it’s gold plated. And I’m very pleased with the results of the gold plate, it’s very nicely done.

Moving on to the reeds themselves I notice you appear to be keeping entirely to cane drone reeds. What's your thinking on that?

I like the tone, the sound, the harmonic content of the drones. And it’s not without difficulty. I remember speaking to Colin Ross years ago who said the supply of cane is difficult and the quality is very unreliable - and he’s right. But I decided from the outset to persist with cane - I like it better. I don’t dislike the composite reeds - the plastic or the brass reeds - I just prefer the cane.

Do you find them easy to tune?

If the reed is right it is stable. And one thing I’ve learned over the years is that you’ve really got to discard a high percentage of the cane and even the finished reeds, because you've got to think of each reed as something that will last for ever. Therefore it has got to be absolutely right. And if it is absolutely right it is as stable as the brass or composite ones.

I know you make your own smallpipe chanter reeds; do you make your own Border pipe

chanter reeds? or cut them down?

We make our own. We’ve just recently started doing that. We don’t cut down Highland reeds - ours are specifically made for the Border pipes; they are a different design.

Do you think there is any correlation between the shape of the reed and the shape of the bore of the chanter?

I think it has been said that the angle of the reed should roughly match the angle of the cone of the chanter. I don’t know if that is true or not. We have our reamers that we use and we have the reed that we use, and the two match. But I really don’t have any experience of the matching of reeds to the bore and the theory behind it.

And smallpipe chanter reeds are probably easier to make - more standard?

What do you find is the most popular pitch for your smallpipes. You said ‘A’ I think?

Probably 90% or more are in ‘A’.

And you have this ‘A/D’ interchange.

‘A’ /‘D’ smallpipes with four drones; two ‘D’s and two ‘A’s. For the ‘D’ chanter you obviously have your two ‘D’ drones and an ‘A’ baritone. With the ‘A’ you forego a baritone, just play with ‘A’ bass and ‘A’ tenor. That’s increasing in popularity with the customer - not with me, because I like to keep the things separate. I think that a set just in its entirety is more satisfactory.

Are the four drones not a wee bit heavy?

Yes. Yes, especially in Blackwood. So I don’t encourage it, but people do want it, so you have to do it.

O.K. The interchange of the chanters: Is this based on the Northumbrian smallpipe system, with an extra piece so that you can take the chanter out without damaging the reed?

Yes, a separate stock for each chanter which fits into a permanent bag stock.

Have you a standard size for this?

Yes, I have a standard size.

Is it the same as the Northumbrian standard size?

No.

Is there a reason why it’s not the same?

Yes. The original 19th century set of small pipes we copied had a 5/8 inch internal diameter for the chanter and blowpipe stocks. It gives a larger clearance between the inside of the stock and the reed than the Northumbrian system. It decreases the chance of damaging the reed when the chanter goes into the stock.

Does it have any effect on the pitch or tone?

Yes; the volume of air within the stock has a large effect on the pitch and tone.

What about other standardisation. This is something about which I have long been beating a drum. For instance, the blow-pipe connection.

I think I’m now on what Julian Goodacre calls the European Standard. I adopted that. It is a standard cone with a wood to wood push fit. I think he got it from the French via Jon Swayne. Anyway, it’s the same as theirs - interchangeable. I think standardisation is a good thing. I think it should happen.

You would favour a day when chanters could be interchangeable from different makers - and bellows ditto?

Yes; very much so. Maybe we should all get together on this and try and standardise sizes.

Can you see any input, perhaps, from the LBPS on this?

That would be a very good medium through which to work, I think. Because even within Scotland - even missing out the Northumbrian side of things - there must be different sizes from all the different smallpipe makers who have now emerged.

Do you detect an increase in the interest in Border pipes?

Yes; very marked. And not only that; people who don’t have smallpipes getting Border pipes as their first instrument. And people who have had my smallpipes over the years coming back for Border pipes. In fact they are, in some ways I think more useful in sessions. Smallpipes get lost if there are more than two or three people playing. And the key, obviously, is going to be ‘A’ unless you’ve got some very sympathetic fiddlers who like playing on the middle two strings.

What do you expect from the Border chanter? ‘G’ sharp? ‘F’ natural? ‘C’ natural? High ‘B’? or are you looking for a standard fingering like the Highland chanter?

My chanter gives a very easy and accurate ‘C’ natural and ‘F’ natural and E flat. I don’t go for the overblown high ‘B’, because I think it makes too many compromises on other aspects of the scale which are too important. I have put high ‘B’ keys on chanters, but I’m not very keen on it. My principal aims are to have the chanter stable, in tune, playing nicely and I try and make it as quiet as possible. That’s very personal.

The fingering of say your ‘C’ sharp, do you do that with the pinkie down or up?

Down.

And your reasoning?

Because most people who come to them have been trained that way. It’s very easy to sharpen the note a bit more and have it playing in tune with the pinkie up. But most people use the closed ‘C’ sharp.

And the playing of the ‘C’ natural would be with your middle finger up, ring finger down and pinkie up?

Yes. And the ‘F’ natural the same.

And the ‘G sharp?

It’s not good enough on my chanter to be taken seriously. It works with the thumb up and the first finger up and the ring finger and middle finger down - I think. An approximation. I do believe, however, that the scale has changed - radically - in recent times. I think the ‘G’ has become much flatter. The ‘G’ used to be, I’m sure, somewhere between ‘G’ sharp and ‘G’ natural.

Has this change come about from mixing with other instruments, do you suppose?

That’s one reason, but I think it was flattening before that in Highland pipe circles. If we're talking about the key of ‘A’ and ‘D’, then tunes played in the key of ‘D’ with a sharp seventh note, even if it’s a bit sharp, sound horrendous. Whereas if you are playing in ‘A’ there are many, many more tunes requiring a ‘G’ natural - the mixolydian mode - than require a ‘G’ sharp. Now it sounds awful when you play a ‘G’ natural when it should be a ‘G’ sharp, but I tend to get round that problem by not playing the ‘G’ at all. Playing another note - ‘E’, or adding an extra high ‘A’. But the big tunes in ‘A’ are quintessentially Highland with that mixolydian mode.

You talked earlier about Reel pipes. They were designed to be played for reels with Highland piping fingering. It suggests to me that they might have a harder reed than the Border pipes?

I don’t think so, I don’t think so. Jock. Effectively they are the same instrument. I think that the Reel pipes were specifically Highland, and played by that most noted piper Callum MacPherson, on whom Iain MacInnes has done quite a lot of work. I remember Iain saying one of the fine quotes was that he could play his Reel pipes at a dance for hours and they wouldn’t go out of tune. And because they were bellows blown he could smoke his pipe all night. It was actually his set that we copied from the museum.

Are people playing them now for reels?

Yes. And that’s happening across the board. The old Scotch step dancing grew out of the

Scotch reels, and it was the standard instrument for playing for reels and step dancing; before the use of the fiddle were the pipes. And that would be Highland pipes or Reel pipes. I think it is a great asset that we’ve regained for our culture, the Border pipes and the Reel pipes. And because we are regaining our vast wealth of dancing in the form of reels and step dancing, to have an instrument to go with that is obviously very, very important.

When you carry out maintenance and repair, what are the most common things you have to mend or adjust?

Chanter reeds suffer, as we talked about before, in the winters over in the States. So if a chanter reed is moved and warped and can’t be fixed, then people need new chanter reeds.

But general maintenance - some people are very good at it, some people are very neglectful.

So for some people I have to re-hemp, some people do that for themselves. It really varies. Some of the leather - I have to oil some of the leather.

What would you recommend for leather bags and bellows?

Neatsfoot oil.

Just on its own?

Yes. Some people add beeswax, melted beeswax. I suppose the more porous the leather the more need there is for beeswax to be added.

How often would they need a dressing - for that is in effect what this is?

They should only do it when necessary. Otherwise there is likely to be a surplus which could run on to the reeds, So I would only do it if it was necessary. And some leathers, if you're lucky, never need it.

What about the inside of the bore. There used to be a lot of talk about oiling the inside of the pipes. Is this still your opinion, that one should regularly oil the bores of drones and chanter?

I don’t recommend it so much. I think the oil attracts dirt and dust and eventually builds up a bit of a residue in the bores. I like the idea of oil going into wood. It’s a nice concept. And I think somehow the wood benefits from being oiled before the pipes are finished, especially Ebony - it’s a very dry timber; much more so than Blackwood which is full of gums and resins. Anyway I don’t think the oil penetrates into Blackwood very much, it just stays on the surface. So I tend to try and get a very highly polished bore and leave it at that.

What would you suggest then - a dry wipe through the bore once in a while?

Yes. With something very soft. Because it is a highly polished surface which scratches easily.

What about your philosophy on playing technique, can you give us a few pointers in that direction?

I think I would say that rhythm is very important - and ornamentation is very important as well. But the ornamentation should enhance the tune and should come as secondary to the rhythm...it should be used to enhance the rhythm. Just because someone wrote E down on a bit of manuscript and stuck in lots of doublings and grace notes and grips and toarluaths - I never regard that as a reason to play all of those.

Not sacrosanct!

No. And because of the competition system and the military taking the pipes on board, I think what happened was the technique became more important because it was an identifiable and an easy criteria on which to judge people. And therefore more and more ornamentation was put in and not always in places that enhanced the intrinsic rhythm of the tune. And because the competition became more and more important and the music - pipe music - became further removed from the rhythms of the dance and the rhythms of the language, then the natural rhythms of the music became lost to technique because of competition. So my philosophy in teaching is to re-introduce the dance rhythms. It’s very much on that style that I teach.

And oral teaching versus dots. You prefer oral to reading music?

Yes. Very much so. Reading music is a conscious exercise which has to be processed in the logical part of the brain. And you can actually see people figuring it out using that side of the brain which is used for logical thinking - then mechanically reproducing the notes.

Whereas if you learn by ear, the music goes in through your ear and comes out of your fingers hopefully via your heart, missing out the conscious part of the brain; the logical thinking part of the brain. Some people have told me over the years that they can’t learn by ear, but I have disproved that. Everyone can. And the sense of achievement and satisfaction for people learning that way is quite astounding. And the other thing I’ve found is that people who have never done it and possibly aren’t so naturally gifted, their sense of achievement is possibly greater. Because they've never done it, they’ve never exercised their ears...tested their ability. And if you do practice it it'll become easier. I find it’s a wonderful way to teach.

And that brings me onto something that has been a lot of interest to me recently and on which Common Stock has run some articles - the Border tunes from Dixon’s book.

Yes, I love them. The Dixon thing happened after I had to stop playing, so I haven’t had a chance to try any of them. A lot of them aren’t great melodies, they’re very repetitive, and they rely very heavily on a strong rhythmic pulse, and when you achieve that, play in the right tempo at the right rhythm they become meditative - the repetitiveness of them, and the way they go round and round with the variations. And that is obviously their appeal. And just two nights ago, on Catriona MacDonald’s programme, Celtic Connections on Radio Scotland, I heard a live set from Martyn Bennett’s band. He took a lot of the Dixon material when we asked him to the Collogue in Peebles, and he struggled with it for a while before he got into it, and then it began to flow through him and made sense to his musicality. And once that happened, he grew to love them, and he’s incorporated them into his band, with a hip-hop backing - and they're fantastic. He’s even singing them now. I love it.

He plays them on the smallpipes.......

And I find that for the most part they seem to sit better on the Border pipes.

Yes, I agree.

That's a difficulty 1 had with hearing him play at the Collogue - he was tending to introduce Highland gracings and on pipes that didn’t, in my view, do the tunes justice.

Yes - although he used Highland gracings they weren’t conventional Highland gracings; well, some of them were. He didn’t lose the rhythm - he didn’t forsake the rhythm for the gracings. And as long as the rhythm stays intact, then I think that’s what is really important. I take your comment about the fact that they do sound better on the Border pipes.

Finally, about the workshop. You've got a team working with you on the production of smallpipes and Border pipes. Can you tell us a little about the set-up.

There are seven of us. I don’t employ anybody - everyone works on a self-employed basis in their own workshops.

It’s by mutual agreement that this happens. There are two turners, Bill Stevenson and Tim Gellaitry, one bag-maker Lawrence Thomson and two bellows makers, Hamish Rankine and lain McGee (Iain also makes chanters). I couldn’t hope for a better team a more highly skilled craftspeople to be working with. I wouldn’t be in business without them.

And the most recent addition to the team is my son Fin - and that’s a joy, knowing that he wants to make a life in piping and pipe-making. And the very wonderful process of passing a craft and a skill from one generation to the next. Because it was actually my Father who started making albeit for a short time before I took over - well we started together really - and Fin will be the third generation. And the wonderful process by which it can take as long as it takes me to say this sentence to you, to pass on a vital bit of information to him that took me 3 or 4 or 5 years to discover. So he can bypass months and years of working it out.

So you can say that some of the problems that your father discovered and overcame are now part of his kit?

Oh yes. Its a great gift for me to see him taking this on. And he’s doing it in a very methodical and patient way - and very diligent. He’s just coming up to completing two years and has worked entirely on reeds and tuning so far. He has done a little lathe work. Im going to get him on to boring soon; doing the internals - because the internals are really important. After this he will go on to profiling the outsides. ,

And you'll develop and discover other aspects as you go along.

Yes. Definitely. And Fin being involved - we’re going to go into a lot of projects which I’ve wanted to do for years, but haven’t had the time. We want to do a tutor; and we want to publish another book of music/tunes; and we want to do all sorts of things - like promoting the Highland pipes; that’s another priority which we are going to be able to do much better now. With Fin involved I now have more time for turning than I used to.

It’s great.............