Half Longs - Develop or Die

Denis Dunn is a piper and archivist who has had a life-long involvement with the Northumbrian Smallpipes and Half Longs (debate continues over the difference - if any - between Half Longs and Lowland or Border pipes). Here he reflects on some of the personalities involved with the recent history of these pipes, and speculates on their future. Note; where he mentions Smallpipes in the article Denis is of course referring to the Northumbrian Smallpipes.

Nearly a hundred years ago the old Northumbrian Small Pipe Society died out from Saturday night boozing, and for twenty years or so very few people continued playing the Small pipes and, as far as I know, no-one was playing the Half Longs let alone making new sets.

G.V.B. Charlton was the 4th son of a Newcastle doctor. The family had been established on the North Tyne for several centuries, but G.V. had moved to Northamptonshire where he had a busy practice as a land agent at Thrapston until his untimely death while on a fishing holiday in Scotland despite emergency surgery. Though never an accomplished player, his love for the North and for piping in particular had remained with him, and he had determined to revive the playing of the Half Longs.

First there had to be some pipes to play, and P/M James Robertson of Edinburgh, already a manufacturer of Highland Pipes, agreed to provide them. There was no definitive historical design to copy, only an assortment of old chanters, drones and bellows belonging to different sets.

In the spring of 1925 there was an historic meeting at Will Cocks’ house at Ryton of the team Charlton had collected round him. The decision was taken that the pipe design would be bellows blown, with common stock drones following the Millburn pattern, and an openended conical chanter copying the Muckle Jock example. The drones would sound A, E & A’. From this design Robertson produced over 100 sets during the next few years.

Despite only tepid enthusiasm by various governing bodies - E.R. Thomas, Headmaster of the Grammar School, was an exception - Charlton was able to get Northumberland Half Long pipe bands started with the Fusiliers, the Boy Scouts, the University O.T.C and the Grammar School O.T.C., and it was with the latter that I was introduced to the mystique of piping. In the spring of 1925 it had been arranged for Ed Merrick, a geologist at Armstrong College, to demonstrate the Half Longs and for Vivian Fairburn, a pupil at the school and a protégé of Will Cocks’, to play the Small pipes at the school assembly. The Head was so impressed he ordered 4 sets as a start for the O.T.C. band.

On the 5th October 1928 the Northumbrian Pipers’ Society was formed, meeting at first in the members’ houses, for a while at Black Gate, but soon thereafter in the Great Hall of the Castle. Once a month during school term P/M Robertson came down from Edinburgh on a Friday afternoon and taught the pipers of the Grammar School band. In the evening, for an hour before the start of the regular Pipers’ Society meeting, he held a further session for anyone who cared to turn up. These were mainly enthusiasts from the School and Boy Scout bands. The fingering technique and the gracing were those of the Highland pipe, as were most of the tunes.

Charlton persuaded several of the nobility and the Musical Tournament to sponsor silver and bronze medals to be competed for at the various village and town shows. Robertson himself presented a silver cup.

Alas the Pipers’ Society minutes show that Charlton’s enthusiasm and staying power were not matched by that of the various quasi military organisations. So poor was the attendance at the teaching sessions that after a year Robertson’s teaching sessions were abandoned. At that time I myself was just starting at Medical School, and for a year I kept attending band practice at the Grammar School; a case of the blind leading the blind if there ever was one. Increasingly my involvement with the Peace Pledge Union conflicted with the O.T.C. and after a year I too gave up the teaching sessions. Exactly when the school band disintegrated does not seem to be recorded. Similarly with the Fusiliers’ and Scouts’ bands. It seems that Brian Ward’s Scout band at Whitley Bay was the longest survivor.

The social and technical upheavals of Hitler’s war were the final strokes for all the Half Long bands. Evacuation scattered the young. The “Pipes O’ Havelock” (1) had no place in moving troops compared to lorry, coach, tank and parachute drop.

The Present Position (as seen from Essex).

After the war the playing of the Small pipes expanded rapidly. Both the number of players and quality of performance soared, and new craftsmen took up the demand for instruments, some becoming professionals. The Northumbrian Pipers’ Society flourished, though its meeting place had to change several times. Residential instructional weekends and local satellite groups as at Morpeth, Alnwick, Hexham and Cleveland kept enthusiasm alight.

No such resurgence occurred with the Half Longs.

In 1994 the Northumbrian Pipers Society published a very useful list of members from many counties in G.B. and from several foreign countries. Unfortunately whether members were players or not was not recorded.

The Lowland and Border Pipers’ Society published a membership directory for the same year along with a note about what pipes each member had and in several cases the pipe maker was named.

229 members were listed and some seventy of these had reported that they had pipes that may have been of Half Long type, e.g. Northumbrian (Half Long or Small not specified), Cauldwind, Border, and Lowland. 10 makers were noted, and half a dozen bands.

Why have the Half Longs not had the upsurge in popularity shown to the Small pipes?

- Loudness

The Half Longs are really an out-door instrument, quite unsuited to indoor playing except in a large hall.

- The Chanter Scale.

This is the same as the Highland pipe with several of the notes different from the mean tone tuning of the modern piano. In particular the very flat leading note is unwelcome to the ear used to mean tone tuning and makes playing with other instruments difficult. Perhaps this is why “Amazing Grace” is so popular with massed Brass and Pipes and Drums. The 7th does not occur.

- Marching.

Except for a few ceremonial occasions there is no call for piping for routine marching.

- Dancing.

It just doesn’t seem to happen except for the occasional New Year's Eve drunken reel.

- Solo playing.

Since there is no-one else to play with this is probably the commonest situation. But what a lonely activity with not even the fantastic gracing and timing of the pibroch player to aim at. What is to be done?

(1) Loudness. Colin Ross tells me that substantially thinning the reeds will allow playing at reduced pressure and so make the pipes quieter.

The timbre of my Highland pipes is much fuller than the Half Longs which are squeaky by comparison. The former has appreciably larger finger holes, but maybe the type of wood is a factor: not to mention the wetter Highland reeds.

The Drones. With the continuous sounding of the bass and treble drones some dissonance is inevitable when any note other than the fundamental is played on the chanter, though less with the Dominant ‘E’. The presence of the ‘E’ drone makes the dissonance a problem greater with tunes played in ‘D’. Personally I had never been disturbed by this until my good friend the late Bill Kirton told me of the error of my ways in playing ‘D’ tunes with the ‘E’ drone on. He felt so strongly that he kindly turned me a little wooden bung to shut the drone off. To my insensitive hearing it made little difference except for the reduction in noise in the left ear.

How much of this dissonance is in the actual vibrations of the fundamental notes and the harmonics producing “beats”, how much it is in the musical ear and how much it is in the theorising mind of the hearer I do not know. “Ears” vary; perhaps mine are very undiscerning.

There is no doubt, however, that the common stock drones have a loudness problem. Sounding alongside the left ear what else can you hear except the chanter? Certainly no other player or singer.

The Bellows. By avoiding the wetting of the reeds that occurs with the mouth-blown pipe, the bellows provide a considerable advantage. Except in very prolonged hot dry weather the reeds remain in good condition however long they are played or lie in the cupboard. Whether this dryness adds to the squeakiness of the pipe I do not know. Bellows are also an advantage during long marches or dancing sessions, particularly for the ageing piper whose lungs are not so strong as in former years or whose teeth no longer can grip the blow pipe firmly.

There is no doubt however that winding the pipe evenly is a little more difficult with bellows contrasted with the mouth blown instrument.

The Music. The scope of this is circumscribed by the chanter scale, but could be unending as the Highland pipe has shown. The nature of the pipe scale and the loudness of the reeds greatly limits the possibility of playing with other instruments. These points were well illustrated when playing at some protest marches organised against the export of live animals through the little port of Brightlingsea. The marchers progression hampering the lorries was to slow marches which could have gone on indefinitely with the use of the bellows blown pipe. Especially when a “sit down” occurred it seemed appropriate to intersperse the Dirges with a brisk chorus of “We shall over come”, but in the third phrase the leading note is unacceptably flat and high 'B’ is off the chanter altogether. Transposing the phrase to the lower part of the chanter was off-putting to the un-rehearsed singers and the piper could not hear what was going on.

He had of course to laugh off the jibe that piping made the agony of the animals worse. Alas the calves are so cramped in the lorries that they have no room to turn let alone vote with their feet like the rats and children of Hamelin and show whether they hated or loved the music.

Playing Technique. Since, in the 1920's there were virtually no Half Long pipes and no pipers, there was no teacher-pupil tradition. Nor does there seem to be any written record. So how should the Half Longs be played? Robertson’s teaching was in direct line with the Highland Regimental Band technique, gracing and all. Separated now by half a century from living in Newcastle how can I opine on how the Half Longs should be played? I don’t even know how many people actually play them let alone how they are in fact being played. Nor do I know how that technique relates to that of the Border or Lowland pipes. I imagine the days of Highland Pipe fingering and gracing are long gone.

What can be done?

Competitions. One stimulus to more and better playing might be the revival at the District shows of Half Long competitions as are so successful with the Smallpipes. But with no tradition of how the Half Longs should be played nor what tunes are suitable to be played on them how are the judges to judge? Even more difficult: who is to choose the judges? The long-running controversy over the judging at Highland piping competitions is not encouraging (2). And even south of the Border there have been doubts (3).

The Smallpipe players seem to have reached the critical temperature and are bursting out with new players, new pipe makers, new local groups and new compositions. How can the Half Long players do likewise? For a start it would be interesting to know how many of them are under the age of say 25. A few years ago when it was suggested that the Northumbrian Pipers’ Society should revert to the last century name “The Northumbrian Small Pipers Society” there were enough voices raised in protest to get the proposal dropped.

Our problem could be tackled from two directions.

First the pipes could remain as they are and the playing technique altered. The range of the chanter can be extended upwards by “overblowing” (and/or pinching the upper note); But what does that do to the drones? (Colin Ross says nothing except possibly momentarily). The pitch of the present notes can be altered by cross-fingering as illustrated by Agnew, Ross et al. But can such dexterity be kept up at speed and controlled by the ear of the average player?

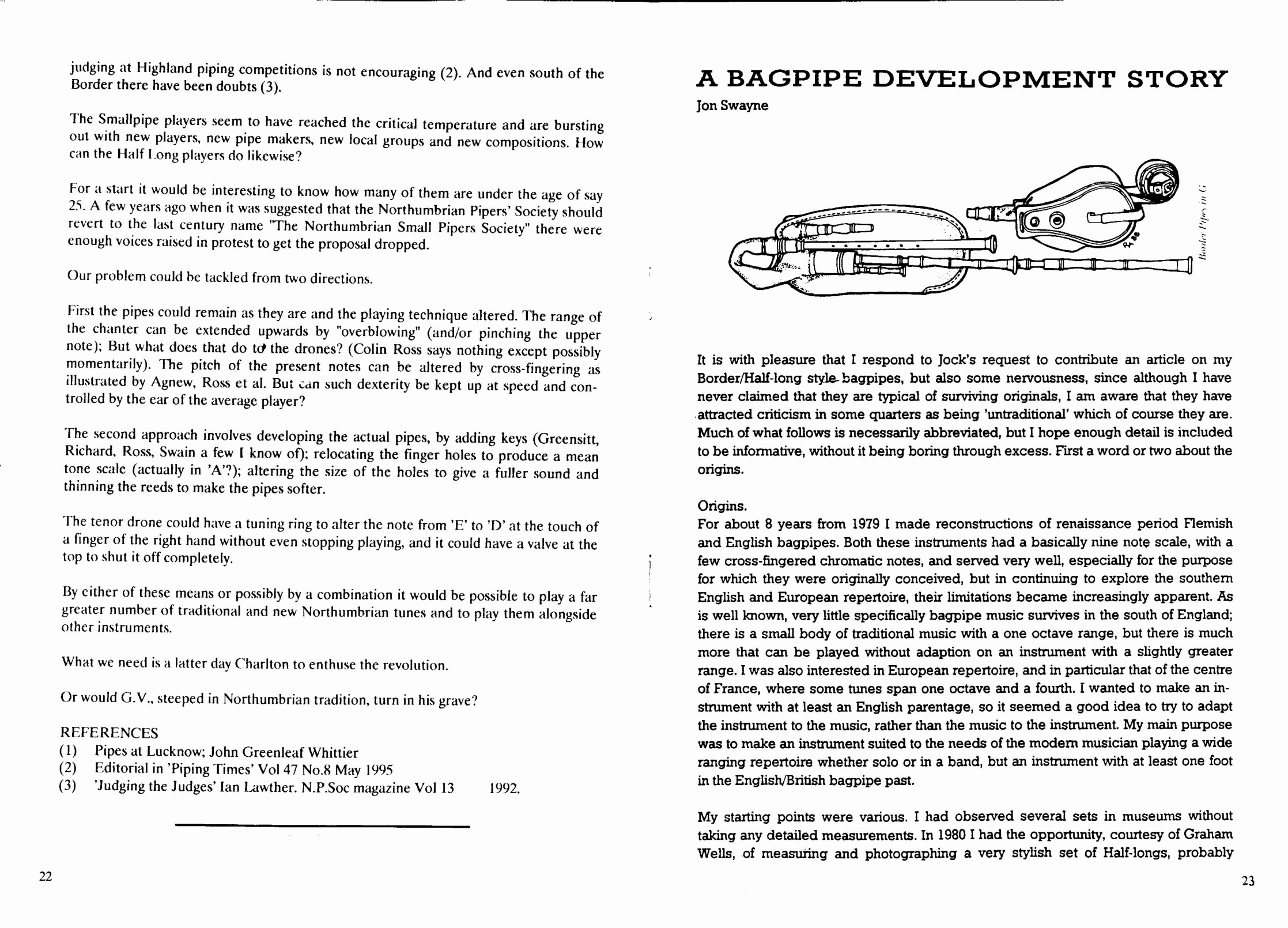

The second approach involves developing the actual pipes, by adding keys (Greensitt, Richard, Ross, Swain a few I know of); relocating the finger holes to produce a mean tone scale (actually in ‘A’?); altering the size of the holes to give a fuller sound and thinning the reeds to make the pipes softer. The tenor drone could have a tuning ring to alter the note from ‘E’ to ‘D’ at the touch of a finger of the right hand without even stopping playing, and it could have a valve at the top to shut it off completely.

By either of these means or possibly by a combination it would be possible to play a far greater number of traditional and new Northumbrian tunes and to play them alongside other instruments.

What we need is a latter day Charlton to enthuse the revolution.

Or would G.V., steeped in Northumbrian tradition, turn in his grave?

REFERENCES

(1) Pipes at Lucknow: John Greenleaf Whittier

(2) Editorial in Piping Times’ Vol 47 No.8 May 1995

(3) ‘Judging the Judges’ Ian Lawther. N.P.Soc magazine Vol 13 1992.