December 2007

A Fiddler Calling the Tunes Shona Mooney Profile

Summer School, Common Ground, 2007

From Harvest to Market - Piping in Cambeltown at Harvest and Fair

Bagpipe Timbers, past, present and future

In the Beginning - LBPS Founder Mike Rowan

Skippin\' the night away Collogue Ceilidh

Review: Book - Over the Hills and Far Away

No.2 December 2007

The Journal of the Lowland and Border Pipers' Society

Detail from painting ‘Campbeltown Fair’ Courtesy Campbeltown Museum & Library

IN THIS ISSUE:

Back to the Borders(4): Friars Carse Summer School(13): The piper’s role in rural society (17):

Bagpipe timbers and their future(20): Memories of a founder member (26):Skipinnish at the Collogue (30)

Treasurer Iain Wells

Minutes Secretary Jeannie Campbell

Membership Pete Stewart

Chairman Jim Buchanan Secretary Judy Barker Newsletter Richard & Anita Evans Editor CS Jim Gilchrist

The Journal of the Lowland and Border Pipers’ Society

Editorial

THE cauld wind pipes revival has been straddling the Highland-Lowland divide of late - though it can doubtless be argued that we have still to establish a satisfacto- ry definition of when Lowland/Border pipes become Highland reel pipes. Last month's LBPS Collogue was held in Bimam, in Highland Perthshire, when a very lively ceilidh dance was blithely propelled by the fine West Highland out- fit Skipinnish, using Border pipes as well as Highland pipes, alongside accordion, whistles, etc.

A report of the ceilidh, and of other pro- ceedings at the Collogue, appears in this issue, while Professor Murray Campbell's edifying and entertaining talk on the physics of bagpipes will appear in the next issue. In the meantime, however, observations that, despite the name and orginal intentions of this society, the Scottish bellows pipes revival has never really caught on in their one-time Low-

Lowland and Border heartland have been greeted by an impressive new album of piping, released this month, which showcases four fine Border players.

Borders Pipes is part of the on-going “Border Traditions” series, produced by Dr Fred Freeman (who gave us a taster at the Collogue at Newton St Boswells two years ago). In this issue we carry Fred's sleeve notes for this important recording, which is released this month and comes highly recom- mended by Gary West and Fred Morrison. A review of it will also appear in the next issue of Common Stock.

Also, courtesy of Keith Sanger, we travel into the West, and the once thriving burgh of Campbeltown and its annual fair, to examine the role pipers once had in rural society. We also take a look at our own history as a society, and report founder member Mike Rowan's talk to the Collogue about the Society's seminal years, as well as recalling the inimitable PM Jimmy Wilson.

After Mike's talk, David Hannay present- ed him with an honorary lifetime member- ship of the Society for his role in its formation, and, looking at a back number of Piping Times from which Mike had quoted, pointed out that its cover was in fact the Hannay tartan. He went on to recall how the piping commentator David Murray had once observed to him (David was kilted at the time) how funny it was to see someone dressed in back numbers of the Piping Times ...

Jim Gilchrist 0131 669 8235

A lad o’ pairts

AT BANFF, by the far-off Moray Firth around 1783, Isaac Cooper provided for a distinguished clientele in the traditional dual role of musician and dancing master. In publishing his collection he observes that the public had been “so much imposed upon by people who have published reels, and called them new and at the same time they were only reels with new names”.

He advertised himself as the teacher of an impressive list of instruments the harpsi- chord, violoncello, psaltery (viol), clarinet, pipe and taberer, German flute, Scots flute, fife “in the regimental style” and hautboy; and of “... the Irish Organ Pipe, how to make flats and sharps and how to make the proper chords with the brass keys. And the Guitar, after a new method of fingering (never taught in this country before) which facilitates the most intricate passages”.

-from George Emmerson's Rantin’ Pipe and Tremblin’ String: A History of Scottish Dance Music, 1971.

Despite the undoubted success of the ‘cauld- wind pipes revival', concerns are sometimes expressed that much of the activity, especially regarding recording, tends not to be particularly focussed on the Border country and its music, so the latest addition to the Border Traditions series of recordings funded by Scottish Borders Council and the Scottish Arts Council is a welcome develop- ment, featuring pipers Calum Galleitch, Gordon Mooney, Chris Ormston and Chris Waite. At a time when the Society has been re-assessing its origins and progress so far,

we reproduce here the album's introductory sleeve notes, written by Dr Fred Freeman, producer and musical director of the series.

The Borders pipes

THE TERM “Borders Pipes” refers to two types of bagpipes that were played on both sides of the Scottish / English border and that have been given various names over the centuries. I have chosen to refer to them as: (1) the Border pipe - an instrument, usually in the key of A now, having three drones from a common stock and a conically bored chanter. Often called a Lowland pipe or a Northumbrian half-long pipe, it has been played well beyond the region of the country to which it is associated. (2) the Scottish small pipe - an instrument, made in various keys but most commonly these days in A or D, having three to five drones and sometimes one or two keys, with a cylindrically bored chanter. For a long time, the critical difference between the Scottish Small Pipe and the Northumbrian Pipe was only the chanter: the former being open ended and the latter, closed ended.

In recent times the history of the pipes and the pipers has received admirable attention in the hands of Pete Stewart, Matt Seattle, Gordon Mooney, Hugh Cheape, Iain MacInnes and so many others who have contributed to this rather excellent journal.

Revival of the Borders pipes

We do know on the testimony of John Stoddart, John Leyden and others that Borders pipes, of all varieties, fell out of favour during the early 1800s though there is ample evidence, with makers like Gunn, Mark, MacDougall, Glen and Henderson continuing to make sets, that a moribund but tenacious tradition did persist underground, probably right across Scotland.

Francie Markis, for example, was a renowned Aberdeenshire Border pipe player who lived from 1823-1904; Jimmie Wilson of Hamilton, who attended early LBPS meetings in the 1980s, had performed on a set of Henderson Border pipes since the 1930s; and so many pipers in the forefront of the revival - Hamish Moore, PM Iain McDonald, Jimmy Anderson, to name a few - have stories about 19th and 20th-century sets they either revived or copied.

various Scout troops in Northumberland. Some 60 sets were duly made, and the troops, as well as Newcastle Grammar School and Armstrong College amongst others, were involved in something of an early revival. Robbie Greensitt, of Herriot & Allan Bagpipe Makers in Northumberland, fondly remembers playing regularly on one of these sets, in the 1950s, with the 13th Whitley Bay, St Paul's Scout Pipe Band.

It was not, however, until later that a serious revival of the Border pipe and Scottish small pipe began to take shape within the Scottish folk movement. In the mid 1960s Jimmy Anderson of Larbert, who is generally, if unofficially, recognised as the founding father of the Scottish small pipe revival, began experimenting with Scottish chamber pipes and

practice chanters. Jimmy, who was a joiner to trade, borrowed wood from Bob Hardie to make wee drones and began plugging-up practice chanters and re-boring them with hand- made reamers in a desperate attempt to create an instrument that would sit nicely, alongside two fiddles and voice, in his group The Clutha. The Highland pipes were altogether too loud; the chamber pipes too soft; both were in B flat - not a great key for fiddlers.

Once a chanter was in hand, the critical problem was to find a suitable reed for it. In the late 60s and early 70s, Jimmy's friends and contemporaries in the folk scene - Rab Wallace, Iain MacDonald and others - would suggest his experimenting with cor anglais and bassoon reeds for the sound and projection he was seeking. Indeed, in the mid 70s, P/M Iain MacDonald (and Dougie Pincock after him) would use one of Jimmy's key of D prototypes, with the modified bassoon reed, in the noted folk band, Kentigern.

In the early 70s, Iain was given further impetus to play bellows bagpipes by one Willie Hamilton of Maryhill, Glasgow, who used to make Northumbrian and various Continental pipes on an old pedal Singer sewing machine. According to Iain, Willie would get Grainger & Campbell to make his long joints for the home grown Scottish Small Pipe he produced.

Being a Northumbrian pipe maker of considerable reputation, and a friend of Billy Pigg and Jack Armstrong, he experimented in the 1950s and 60s, with some degree of success, with a hybrid Northumbrian-Scottish reed for the Small pipe. On Willie Hamilton's death, his widow would pass on to Iain 17 sets of her husband's pipes - uilleann, pastoral, gaita, bombarde and more - which formed the original core of the large collection Iain now possesses. Willie Hamilton is more than a footnote to the revival.

Meantime, in 1975, according to Eddie Maguire, Rab Wallace would borrow a set of drawings of an old Border pipe from an Inverness museum and have it copied for playing in his group, The Whistlebinkies. He would also, by 1983, be performing with the ‘Binkies on a set of Jimmy Anderson small pipes in E flat, based upon a 19th-century set of MacDougall of Aberfeldy small pipes Jimmy saw in the Scottish National Museum.

Colin Ross, a Northumbrian pipe maker, who had taken note of Jimmy Anderson's early endeavours and, according to Jimmy, made “helpful” suggestions, began himself to puzzle over the reed problem. Moreover, in the late 70s, he had an order from a Liverpudlian for something he had never made before: a Scottish small pipe. After experimenting, unsuccessfully, with practice chanters and longer Northumbrian reeds, he decided, instead, to adapt the length of the chanter to the standard 2 inch Northumbrian reed size and, with that bit of technology, popularly advanced the revival of the Scottish Small Pipe by light years. He, then, began studying the design of old 18th century sets of Scottish Small Pipes from the Cocks Collection and adapted a design to suit the keys the modern folk pipers

wanted: mainly, D and A. Artie Tresize, Iain MacIinnes, Gordon Mooney and Hamish Moore would be amongst the performing pipers in the early 80s to play Colin's instruments. And, in fact, Hamish avers that it was primarily Colin who provided the sophisticated reed technology required to develop the Small pipes fully.

In the early 1980s, again in Northumberland, Robbie Greensitt, working independently, would develop the Border pipe in conjunction with Joe Hagan at J & R Glen bagpipe makers, Edinburgh, and, a few years later, would modify the design of the Scottish small pipe, in his words, “through adding both tone holes and evenly spaced holes on the chanter”. Richard Evans, a pupil of Colin Ross, also began making Scottish Small Pipes in 1980-81, initially with two metal keys on the chanter in order to play high B and high G sharp. In 1986, Jon Swayne of Glastonbury, following on from a design he saw in a book by Cocks, would, initially, develop a Border pipe in G for playing in his group Blowzabella.

Just a few years later, he would be making sets in A, with Highland fingering, for pipers in Scotland. Hamish Moore, for one, was impressed with Swayne's instruments, seeing them as amongst the first new generation Border pipe suitable for indoor ensemble playing.

A serious revival was underway. In 1974, Mike Rowan, after purchasing a set of North- umbrian half-longs at a Scout hall in Stockbridge, Edinburgh, began a quest to discover more about what appeared an unknown quantity: the Border Pipe. He, firstly, approached Hugh Cheape at the National Museum and, then, at Hugh's suggestion, Gordon Mooney.

With characteristic enthusiasm Mike organised his first formal meetings with Hugh and Gordon in 1981, designed a logo and founded the Lowland and Border Pipers Society in that year. Fortunately, he then discovered Jimmie Wilson of Hamilton who, to his mind, was “probably the last Lowland (Border) piper in the country to be taught by a Lowland piper”. Jimmie, as we mentioned earlier, had been performing publicly on a set of Henderson Border pipes since the 1930s - in shows like Johnny Armstrong, and, aside from his splendid wartime stories, had interesting things to say about the reeds and the instruments.

The rest is history. Hundreds of pipers round the world now play Scottish Borders pipes. As Hamish Moore put it, “no other movement has changed the face of piping, so quickly and so profoundly, within such a short space of time”.

The Northumbrian connection

In many respects the revival of the Scottish Border pipes reflects a larger social, political and cultural reawakening within Scotland. Vernacular traditions of language and the arts, either surviving underground for centuries or barely surviving at all, are now coming to the fore as Europe and the world begin to recognise the importance of minority cultures.

Nonetheless, with this recognition comes undeniable responsibility. Scotland is, and has always been, as Hamish Henderson put it, “a healthy hybrid”: a mix of Celts of all kinds, Angles, Vikings, Flemings, Normans, Sephardic Jews and others. By our very nature, ethnocentricity should have no place in our re-emergence as a unique cultural entity. Generally speaking, we have no problem in acknowledging the Irish connection that, from the Scotti, gave us the very name of our country and, over the centuries, gave us Gaelic language and several shared musical traditions. Similarly, we happily accept the strong Norse connection with Shetland, Orkney, Caithness and elsewhere.

More problematical is the Northumbrian connection, hardly mentioned in our cultural histories but, clearly, as relevant to our Lowland traditions as the Irish and Norse heritage are to the Highlands. In the 7th century the Angles of Bernecia or northern Northumbria spread into southern Scotland, changing Dun Eydn to Edinburgh and, very significantly, giving us a language that was eventually called “Scots”: one of our national languages. In the course of time, the Anglian tongue of Northumberland, under the linguistic domination of London and Oxford, would be relegated to a mere patois as the Scots tongue grew and, then, flourished, especially from 1450- 1603, as a European language with a rich literary, courtly and civic tradition. Linguistically speaking, the bairn had become the mother. “Geordie”, for example, the colloquial tongue of northern Northumbria, has long been considered a dialect of Scots.

But there is more to the liaison than just that. As the 18th century French philosophers rightly averred, language is more than a matter of words. It embraces the whole national “genius” of a people: their humour, values, interests. It is not surprising, then, that our Anglian brethren sustained a lively tradition on the small pipes which, in Northumberland, eventually became the Northumbrian pipe, and on half longs, their version of the Scottish Border pipe, as well as a repertoire and style of playing which was shared on both sides of the border. Gypsy pipers, like the Allans, performed and obviously influenced performance in the Scottish Borders as well as in Northumberland.

Moreover, as mentioned earlier, the firm of Robertsons of Edinburgh was directly involved in an attempt to revive the half long pipes in Northumberland; and several Northumbrian craftsmen - not the least of them, Colin Ross and Robbie Greensitt - have made a colossal contribution to the Scottish folk movement through the pipes they have skilfully adapted for a new generation of Border pipers in Scotland. Add to this the part played in the resurrection of the cittern, by makers like Stefan Sobell, and the contribution of the Northumbrians to the Scottish folk movement bulks very large indeed.

If we fudge the Northumbrian connection, we belie another significant part of our cultural heritage, and, we ourselves, force the truth to go underground. We must have the discernment, the maturity, on the one hand, to differentiate between London political

domination, the imposition of Ox- Bridge and BBC cultural and linguistic values inflicted upon us over the centuries and, on the other, the rich Anglian heritage that should be fully appreciated alongside Norse, Irish and other elements in the Scottish melting pot.

Thoughts on a Border piping style

In endeavouring to do justice to Scottish Borders piping, where virtually all traces of the indigenous tradition had disappeared, one, then, would naturally look to pipers who had a foot in both Northumbrian and Scottish camps. In selecting players for the CD, I auditioned quite a few in order to find just the right people for the job - and I apologise to all those whom I rejected.

It was enlightening to work with two pipers who had come to Borders pipes with different piping backgrounds yet arrived at the same conclusions about the instrument and its music. One of them, Chris Ormston, had begun as a Northumbrian piper; took up the Highland pipes whilst at university (1979-82), ‘with one eye on becoming a Border piper'; then, under the influence of Colin Ross, progressed to Border pipes and small pipes in the late ‘80s. The other, Gordon Mooney, ran the progression in something of the opposite order. Gordon began as a Highland piper; took up the Northumbrian pipes in the mid 70s, regularly travelling through to Northumbrian pipe meetings with Graham Dixon, who had become a friend and mentor; then, under the influence of Jimmy Anderson and Rab Wallace, fellow members of Muirhead's Pipe Band, fully focused his attentions on Borders pipes (of every variety) from about 1981-82 onwards.

Their respective conclusions about style were obvious to me as we worked through the material. Both aver that Northumbrian piping is characterised by a simpler - or to use Chris's description, “less chirpy” - gracing. In practical terms this meant that, in approach- ing the

Scottish Borders tunes, Chris has consciously worked to achieve, but in his own idiom, the simplicity of Northumbrian pipers like Tom Clough, who used “no open gracing”. Gordon describes the “conscious effort” he made in “removing heavy gracing ... freeing up the musicality”, after falling under the spell of Joe Hutton, Anthony Robb, Billy Pigg and other noted Northumbrian pipers. For Gordon Mooney, the historical linchpin of the tradition were the gipsy Border pipers, like the Allans, whose music and style survived in the Northumbrian tradition.

To my mind, the Borders instruments, generally, like the music itself, develop their intensity from a different source than Highland piping. Instead of the cut of birls, as in Crossing the Minch, or the compulsion, for example, of doubling and tachum variations, as in the penultimate section of Blair Drummond, the Borders pipes carry the listener along on a series of upward and downward runs and tickling leaps, as in Duns Dings A, Hey Ca Thro or Wee Totum Fogg. Moreover, the use of ornaments does not tend to follow a fixed pattern the way it does in Highland piping: eg, the wee doubling and birl tags at the end of each phrase in a Highland march. Instead, the Borders piper will use his ornaments sparingly and inconsistently, the way a tasteful uillean piper uses his regulators for varied expression. Listen intently on the album to Chris Ormston's use of tremolos in Cock Up Your Beaver or Chris Waite's use of them in Seventeen Minutes to Midnight, and you will see exactly what

I mean. There is no fixed pattern.

A note on the musical arrangements

The musical arrangements are throughout, essentially, by myself, working in dialogue with the players. Pete Stewart, in his excellent study of the tradition, The Day It Daws, argues that the Borders pipes were indeed used as an ensemble instrument. Hamish Moore maintains that the whole “social context of the instrument has changed, from outdoor per- formance to the mixed session and folk band”. I have chosen to set the Borders Pipes in an ensemble context, where, to my mind, the moving contrapuntal lines are revealed in their best light.

The Tunes

For 300 years the Borders pipers - in Jedburgh, Hawick, Peebles and elsewhere - awakened the townsfolk and called them to their beds; performed for civic functions and common ridings; for weddings and dances, spontaneous rants in the fields and cemeteries. The tunes chosen for the CD reflect this lively range of musical activity. Without being too precious about it, one can affirm that some of these are indeed Border tunes that were played in the past; some of them might have been played; others just lie quite nicely on the Borders instruments. The splendid Burns tunes which I have chosen probably fall into all three categories.

Fred Freeman, producer of the newly released Borders Pipes album, is offering the CD for just £8.00 (inclusive of postage) to LBPS members.

Send cheques to Dr Fred Freeman, 76 Braeside Park, Mid Calder, West Lothian, EH53 OTA.

A fiddler calling the Tunes

AT THE beginning of October 2007, I was appointed the new Traditional and World Music Development Worker for the Scottish Borders Council, based within the arts development team at Library Headquarters, St. Mary's Mill in Selkirk.

The post is funded by the Youth Music Initiative (YMI), with a mandate that we ensure every child

Shona Mooney development worker

will receive one year's free music tuition by the time s/he reaches P6.

In 2003, the Scottish Government (then the Scottish Executive) established the YMI, making a commitment of £37.5million over five years. Since then, the YMI has made a substantial difference to young peoples' experiences of music-making, both in and out of school. The former post holders, Iain Fraser and Jon Bews, contributed enormously with developments and achievements ranging from: a taster session in “son” music (Cuban traditional dance music); a sing-along workshop from Newfoundland duo Jim Payne and Fergus O'Byrne; and an introduction to Ghanaian music. These workshops have helped the children to develop an understanding of the various musical cultures around the world and how they differ from our own traditions here in Scotland. Helping schools to maintain weekly workshops in traditional and world music is an area to which I'd like to pay great attention. No matter how exciting or inspiring a one-off workshop can be, I believe it is also important to sustain motivation, widen understanding and continue exploration in a particular musical activity. Therefore, we propose to layout long-term workshops to run in addition with taster experiences - enabling the children and community to mature and flourish.

In 2005, I completed a BMus in folk and traditional music at the University of Newcastle. After gaining my degree, I became a freelance fiddle teacher and musician, working part-time at the Sage in Gateshead, and within bands such as the Unusual Suspects, Borders Fiddles, the Shee, and leading my “solo” project, the Shona Mooney Band. Winning the 2006 BBC Radio Scotland Young Tradition Award really encouraged me and helped to raise my profile as a fiddler. Part of the award enabled me to release a debut album and perform internationally.

Much of the material that I recorded on my CD Heartsease came from Borders manuscripts and archive Borders fiddle recordings. This music has a very special place in my life - it resonates within me. So as you can imagine, I was incredibly excited to be informed of an employment opportunity to promote and develop the music that I love so dearly. I will continue to perform within my bands and hope to be able to bring my experience as a musician into my job involving the community in performance situations.

The arts development team I work with offers an exciting programme that provides opportunities for young people to learn, play and perform, offers facilities such as a new traditional music and song education pack, promotes the Borders Traditions website, primarily for archive collections (check www.borderstraditions.com), developing a concert programme for the Borders, supporting the CD label Borders, and encouraging the inclusion and appreciation of diverse music cultures within the school and community.

Currently I'm teaching 19 fiddle pupils in four different schools: Caddonfoot Primary, Yetholm Primary, Morebattle Primary and Jedburgh Grammar, and will be helping Chimside Primary School, who have just had a “Determined to Succeed” award, to offer after-school workshops in capoiera and samba. Plans for a taiko drumming day are under- way and I hope to work in partnership with my own trio and three instructors (Fantoosh!), who teach in the Borders. The project is entitled “Two Traditional Trios: playing together in a band”. I hope to explore the process of traditional band arrangements with secondary school students culminating in a performance in a local venue. And in the New Year, we envisage taking a bus trip to see the Unusual Suspects perform in the Glasgow Royal Concert Hall, giving young musicians from the Borders the opportunity to hear world-class musicians at the Celtic Connections festival.

Another strand of my work has been to promote the newly released fifth volume in the Borders Tradition CD label, Borders Pipes (see previous article). Dr. Fred Freeman researched and produced the recording project by working in dialogue with the musicians on the recording - Gordon Mooney, Chris Ormston, Chris Waite and Calum Galleitch, accompanied by Marc Duff, Ian Anderson, Angus Lyon, Brian Maynard and myself.

The Scottish Borders have their own traditional music centre, based in Selkirk High School, that offers after-school tuition in voice (Hilary Bell), pipes (Andrew Bunyan), accordion (Ian Lowthian), clarsach (Elspeth Smellie) and fiddle (Barbara Mythen). There are no charges for the lessons, instruments are provided, but sheet music/accessories must be provided by the student. This centre has been running since 2000 and the pupils perform regularly at festivals in and around Selkirk.

My aspirations for the future include combining musical talents from all over the Borders region, mirroring the Folkestra project in the North-East of England. The possibility of a regional folk ensemble that could perform collaboratively with its English counterpart could produce a potentially awesome noise! I also write for the local What's On magazine which is printed seasonally, documenting the region's traditional music and keeping everyone up to date with concert performances, folk club gigs and community workshops. You can contact Shona Mooney on 01750 724901, or e-mail her on This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.. uk

Piping for peace and plenty

Helen Ross reports on the 2007 summer school, part of the Common Ground festival at Friars Carse, Dumfries

THE LBPS summer school ran from 29 July to 3 August, and was again ably organised by David Hannay.

There were 13 participants at the school, including three boys from Lockerbie who were sponsored by the LBPS for their tuition fees. Three others came from furth of Scotland - from England, Canada and Germany.

As in recent years, the summer school was held as part of Common Ground Scotland, but the location was suddenly moved from Glaisnock House in Cumnock (which had fallen foul of fire regulations) to Friars Carse Country House Hotel, at Auldgirth, just north of Dumfries. It was situated on the River Nith, close to Ellisland farm where Burns farmed unsuccessfully for three years and wrote some of his major poems, including Tam O'Shanter. There was not room for everyone to stay there, and the LBPS members were banished to Thornhill. I stayed in the Thornhill Inn, and some of the others in the Buccleuch Arms. For the first night I had a room above the noisy bar, with rock music blaring till 1 a.m., but I managed to change rooms.

Common Ground was split between music at Friars Carse and arts and discussion at the Allanton Sanctuary, about a mile away. Pipers were down in the basement at Friars Carse,

- a bit cramped, but otherwise OK. Meals were good, but always late. Coffee was some- times non-existent, and beer very expensive (when the bar was staffed).

We arrived on the Sunday afternoon, had a meal, and were entertained by some of the tutors. On the Monday morning Richard and Anita Evans gave a workshop on bagpipe maintenance and reed making. For tuition, pipers were divided into two groups, “beginners” and “competent”, although it was unclear which group was best. The beginners contained the three Lockerbie boys who were excellent Highland pipers, and immediately played brilliantly on the smallpipes. For some reason Jim Buchanan joined that group. There was also Harry, who was starting on the smallpipes but also played the guitar.

The rest of us crowded into the competent group, gaining a little more space when one of our group quit (he didn't like playing from sheet music written for fiddlers, because it didn't have all the grace notes written out). Our tutors were Chris Gibb and Neil Patterson, who alternated between the groups in the morning. They taught mainly Highland rather than Border tunes, but were excellent teachers. Many of us had been attending LBPS summer schools for several years, and it struck me that our playing really had improved. All our pipes were reasonably in tune, making communal playing much more pleasurable than in the early years.

In the afternoon we were free to join other classes. Most of us continued piping for an hour, and were joined by whistlers. I then moved on, with my concertina, to the “Slow Jam”. It was led by Jon Bennett, and it turned out to be a folk orchestra, playing arrangements by Jon himself. We had to choose six tunes to learn over four days - Horses’ Brawl, Mrs Macleod of Raasay, St Keverne Feast, Ryan’s Polka, The Piper’s Cave and two Playford Tunes (Portsmouth and Going to Newcastle). Jon wanted the polka and Mrs MacLeod, but some of us (me) felt that Mrs MacLeod wasn't suited to a slowish arrangement, and per- suaded him to accept the delicious Horses’ Brawl. After dinner I joined the Gospel Choir, energetically led by Heather Heywood, then at 8pm there was an evening concert given by some of the tutors.

We were kept well informed about the evening concerts and other events by The Groundling, a daily news sheet produced by the Glasgow singer and songwriter Adam McNaughton and reminiscent of the Daily Prophet at Hogwarts School of Wizardry.

On Monday Dunkeld met Dundalk, in the shape of the fiddlers Pete Clark and Gerry O'Connor. Fear-an-taigh Willie Slevin asked them to describe the difference between the Scots and Irish styles: Pete said they were like different speech accents, while Gerry said the Scots was tighter and the Irish more lyrical. The Groundling concluded that the difference did not matter, and that the combination was greater than the sum of the differ- ences.

On Tuesday we had Heather Heywood and Kirsteen Graham singing Scots and Gaelic songs. Heather was magnificent on Young Waters (my favourite sad Stirling song); Kirsteen sang some great puirt-a-beul, and the two together sang MacCrimmon’s Lament in both languages, against a steady drone on Neil Patterson's pipes. Wednesday was Neil Patterson and Adam McNaughton.

Neil played a hilarious pipe version of The Hen’s March to the Midden, clucks and all, while Adam McNaughton was in great voice as usual. Thursday was the Gospel Choir, and the audience enjoyed it as much as I did. Then there were late night sessions for those with stamina. LBPS members tended to slope off to Thornhill for a drink at the Buccleuch Arms, with a piping session one night.

On Thursday afternoon we all went over to Allanton Sanctuar to join in the World Peace Flag Ceremony and provide some music. Allanton is the European sanctuary of the World Peace Prayer Society, and sports many four-sided Peace Poles, with four languages for “May Peace Prevail on Earth” - English, Gaelic, German and Japanese. The organisation was founded in Japan in 1955 by Masahisa Goi, and now has a headquarters in New York state. I remain to be convinced that preaching to the converted assists world peace. My own suggestion is that all world leaders should be made to learn a musical instrument and play together in a ceilidh band. On second thoughts, pipes should be excluded - wars might be fought over the correct timing and gracenotes!

The Flag Ceremony involved national flags being moved from a stand to a circular display around a Peace Pole. Bits of the UK were represented at the end, amid some confusion: there was a Saltire for Scotland, a St Patrick's cross for Northern Ireland, a Welsh dragon, and also a Union Jack, but no St George's cross for Merry England. There were some mutterings about this, but I could not hear how it was resolved, as I was trying to pay attention to keeping in time with the other pipers on Da Merrie Boys o’ Greenland. This was a forlorn hope, as our end of the lineup was nobly led by Harry on the guitar while the other end was led by Neil stamping his foot in an effort to keep us together.

Never mind. We all went on to sing A Man’s a Man for A’ That, and finally Neil played

the Highland pipes from the tower of the Allanton building.

Friday morning was the final concert, at which we again strutted our stuff, this time in the main lounge at Friars Carse. It was exhausting, but we were revived by the final splendid lunch. I am looking forward to more of this next year - though the evening sessions would be better if the pipers could get accommodation on the main site.

Melrose looks to the west

George Greig previews next March's Melrose teaching weekend, which will have a distinct Irish accent

THE 2007 teaching weekend at Melrose had as its theme “Rhythm and Dance” and enjoyed the best attendance of recent years. The next weekend's theme will be ‘The Irish Connection”, running from 7-9 March, 2008, again in the George and Abbotsford Hotel.

Why “The Irish Connection”? At a previous teaching weekend, Hamish Moore introduced The Rock and the Wee Pickle Tow and I realised that I already knew it as O’Sullivan’s March. The last competition heard a fine rendition of The March of the King of Laois, and Allan MacDonald plays this tune back to back with the piobaireachd Duncan MacRae of Kintail’s Lament, suggesting shared ancestry. And the list goes on: The Haughs of Cromdale appears under the titles, O’Neill’s March and The Green Cockade, as well as a Gaelic name which translates as How the Kale was Spoiled. What these few examples show is that people and tunes moved around much more than was once supposed. The intention is to explore this common heritage.

We have a fine line-up of tutors - Allan MacDonald, Malcolm Robertson and Lee Moore, specially chosen for their teaching ability and knowledge of the cultures. Allan is a consummate musician, as will be confirmed by anyone who was at the invitation concert or who saw him in The Highland Sessions on TV. Malcolm and Lee, also fine pipers, bring the more obvious Irish connection - Malcolm spent a number of years in Terry Tully's St Laurence O'Toole band while Lee hails from Dungannon.

This promises to be a great weekend and, like the last, will cater for all levels of ability, so no one should be deterred. To ensure that class sizes are not too big, places are limited and allocated strictly on a first-come-first- served basis, so early booking is recommended - use either the forms with the Newsletter, the web-site or contact me directly at This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

Campbeltown Fair, painted in 1880 Courtesy Campbeltown Museum & Library

From harvest to market

Keith Sanger looks at the former role of the piper in rural society, and warns against making too many assumptions.

WHILE there is a tendency to compartmentalise piping into neat boxes with Highland/ military in one and Lowland/town pipers in the other, there was actually a large and common middle ground shared by nearly all pipers. Professional specialisation is a relatively modern concept and up to the 18th century, even in Scotland's largest towns, most people had one foot in the countryside, which would have been only walking distance away.

Food consumed a very large portion of relative income and the success or otherwise of the harvest had an immediate effect at all levels. Even at the very top of the piping tree, where the piper held land in exchange for his piping duties, it was primarily the raising and selling of his “beastes” or cattle that actually produced the income.(1)

When it came to harvest it tended to be a case of all available hands, and even as late as the Napoleonic wars there is evidence, usually from contemporary newspaper reports that the various fencible regiments, who were mostly quartered on the local populations, voluntarily pitched in to help at harvest time. In one instance the correspondence of the Breadalbane Fencibles shows that even the 13 musicians of the regimental band were offered as reapers. In this case the help was as labour, but harvesting was hard work and the

use of a local piper to give encouragement goes back probably as far as the point that the instrument became loud enough to carry to a band of open air workers. It was certainly an established practice by 1574, when a payment “To ane pyper to play to the scheraris in harvest, £4” was recorded in the accounts of Douglas of Lochleven in Fife.(2)

Exactly how widespread the practice was and when it was discontinued is a more difficult question to answer from the limited recorded payments so far identified. Certainly on the large North-East estate of

instances it is, of course, an

assumption that the pipers were being paid to play while the work

Campbeltown Fair detail, showing piper Donald Michael and left-hand bellows - artistic licence?

was in progress rather than providing the music for dancing after the work was over.

Following a harvest, even on a “self- sufficient” smallholding, a portion of the produce would still need to be sold to meet any extra levies which were due. For example, church dues, or a portion of the schoolmasters salary and, in one case of a piper in Perthshire, what was described as 1/3 of a Crew wedder rendered at 11 shillings and 8 pence in money which turned out to be his portion of supplying a sheep as victuals to the crew of the local boat.(4)

For those close to a town, access to a market was easy and frequent, but for most of rural Scotland it was a case of the market had to come to the seller and there had grown up a regular system of fairs and markets.(5) These were usually held under the authority of the local laird and, as they involved large gatherings of people, required policing.

In the days before a police force was established, this function also fell to the laird, although he usually devolved it to his local Ground Officer or Chamberlain who recruited a reliable body of “Stout Lads” to act as a guard, along with a piper. An account of the fair held at Kenmore at the east end of Loch Tay describes how the guard would mark out the boundary of the fair by marching around the perimeter with the Breadalbane piper. The guard then returned to the guard-house to be ready to deal with any disturbances, although what role the piper took thereafter is somewhat unclear. It is probable that as the “officially sanctioned” piper in attendance he was able to pick up additional payments from the people attending the fair for providing music for dances and other such activities. It would certainly go some way towards the unhappiness expressed by John MacGregor, the aforementioned Breadalbane piper, when he petitioned the Earl in 1790 complaining that despite he, and

before him his father, having been employed for the previous 60 years as pipers to the guard, the Ground Officer was replacing him with Donald Fisher, the estate's other piper.(6)

Since the payment was apparently only 2 shillings and sixpence for each fair or market, the fuss made at its loss would certainly imply that the position of piper in attendance was the key to further monetary gains. As payments for attending markets go, it was far from the highest recorded: among the accounts for the Dalrymple family, the Earl of Stair, there is a payment for July 1674 to Item to the drummer and pyper at the fair day in Cranston £2- 18sh, which assuming an equal share to each musician would give the piper in Cranston considerably more than the Breadalbane rate.(7)

How long the practice of having a piper attending to the harvesters continued probably differed considerably from area to area. When the Earl of Eglinton commenced his new model village at Eaglesham in 1769, the agreement between him and his tenants concerning, among other matters, the village's agricultural land, also required the Earl to provide a piper for the use of the inhabitants, who in the terms of the agreement, was to play through the town morning and evening. But it is clear that the piper would be used for other functions from a claw back clause whereby the Earl would receive one shilling from each wedding the piper attended to help defray the expense of keeping him.(8) It is therefore quite likely that the piper there would also have been used by the Eaglesham folk at harvest. After all, from the piper's point of view, if he was not playing to the harvesters he would most likely have been required to actively help and harvesting was backbreaking work compared to just playing his pipes.

In terms of the pipers attending at fairs and markets the requirement for providing a local guard would have fallen away with the establishment of the more formal national police forces. However, unlike the case of the poor town piper of Kelso, where the inhabitants raised a subscription in 1786 to purchase a barrel organ to replace his pipes,(9) markets still attracted pipers, albeit on a less formal basis and this did continue quite late.

The picture of the Campbeltown Fair in Main Street which opens this article, painted in 1880, clearly shows a local piper called Donald Michael playing for two dancers. The closeness of spread of the three drones on his shoulder might indicate a common stock, but the pipes are clearly not mouth blown and a bellows seems to be shown secured to his left elbow, the same arm as the bag, artistic licence perhaps?

- Holding land for piping duties was not purely a West Highland custom, in 1695 a piper called Patrick Syme in Coathill of Cluny received a tack of 2 acres of land in Concragie (a few miles west of Blairgowrie) for his lifetime in return for his services. ( National Archives of Scotland, GDI6/28/186)

- Sanderson, MH B, Scottish Rural Society in the 16,h Century, p 21. Quoting National Archives of Scotland, (NAS), RH9/1/3. (3)NAS, GD44/544/9/19 andGD44/655/l/672

(4)NAS, GD50/138/13/10/1

- Fairs were normally annual while markets were usually weekly or monthly, but in contemporary usage the terms seem to have been

- Quoted in Black, RIM, Scottish Fairs and Fair-Names, in Scottish Studies, No 33, pll and 44; for John MacGregors petition see NAS GDI 12/11/2/2/15.

(7)NAS, GD135/261/13 (8)NAS, GD3/3/11/12

(9)NAS, GD1/811/1, A list of subscribers in Kelso, promising to pay £6-6-0 to Mr Robert Nicol for the purpose of purchasing a barrel organ to go through the town of Kelso morning and evening in place of the present Scotch bagpipe, 5 June 1786

Bagpipe timbers, past, present and future

THE CHARACTERISTICS of suitable timbers for the manufacture of bagpipes can conveniently be divided firstly into those physical features which arise from the nature and arrangement of the cell structure of the timbers and secondly from the presence of other materials which, for the moment, we shall refer to as MISCELLANEOUS DEPOSITS (see Appendix II).

There are four main PHYSICAL properties to consider, bearing in mind that none is absolute in itself and that one characteristic may modify one or more of the others.

The first of the PHYSICAL properties is that of density. This can be loosely defined as the weight of a given volume of a substance in relation to the weight of the same volume of water. Thus, suppose that 1 cubic foot of a particular timber weighs 68 1/2 lbs and a cubic foot of water weight 62 1/2 lbs, then by dividing 68 1/2 by 62 l/2 we obtain a density of

1.09 for the timber.

Density is of major importance since it affects the resonance of a timber, and the densities of cocus wood, partridge wood, ebony and African blackwood all fall within the range of 1.1 to 1.2 when the MOISTURE CONTENT of the timber is about 12 per cent. I will refer to moisture content later. In comparison with these densities, those of the indigenous timbers used before cocus wood etc became available varied between 0.75 and

0.85. It is clear that the resonance of pipes made from the indigenous species must have been inferior in tone to those of today, since the density of blackwood, for example, is half as much again as that of the indigenous species.

A second physical property affecting musical quality is the STRUCTURE of the timber. For clarity and richness of tones, a timber must have a FINE, as opposed to a COARSE texture.

A third physical factor affecting musical quality is SHRINKAGE. As we know, all timber shrinks as it dries. Suppose we represent a log thus:

As it dries out, the outer layers shrink on a core which remains wet and therefore the same size. Something must give, so the out layer splits over the wetter core. It is of great advantage, therefore, to cut up the log as after felling as possible into the sizes required, and in the case of blackwood this is now generally done. The ends are coated with wax to retard end-drying and related cracking.

There is a great deal of mythology attached to timber seasoning, but in point of fact, effective seasoning is no more than controlled drying to a point where the remaining moisture is in equilibrium with the average relative humidity of the environment in which it is to be used.

Considering shrinkage in more detail, we suppose that the log shown overleaf is being

The square ABCD in the section on the left represents a chanter blank and with respect to the growth rings, the face AB is a tangential face while the face BC is a radial face.

Shrinkage on the tangential face can be up to twice that on the radial face, so that when the chanter blank is properly seasoned it is no longer a square in section but oblong as shown above.

dries out. The deformity is exaggerated in the figure for the purpose of illustration above, but in reality we know that a deformation of only a fraction of a millimetre will affect the acoustical properties of the instrument.

Now we shall consider a fourth factor physical factor, namely DIMENSIONAL STABILITY. Let us assume that we have a chanter made from fully seasoned timber. Over its useful lifetime the chanter will be exposed to widely different moisture conditions, depending on how wet a blower the player is and the humidity of the environments in which the instrument is played. Minute dimensional changes occur in response to such variable conditions. Any wood, therefore, in which tangential and radial shrinkages or expansion are approximately similar will retain the circularity of the bore to a greater extent than those in which radial and tangential shrinkage differ widely. The presence or absence of natural waterproofing agents in the wood will greatly increase dimensional stability and of course the example of such a wood par excellence is the African blackwood tree.

Earlier I said that timber characteristics can be divided into PHYSICAL and MISCELLANEOUS DEPOSITS. WATER is one of the miscellaneous components of all timbers, and in some species such as balsa, can weigh in freshly felled logs more than ten times as much as the dry wood matter itself. In others, such as blackwood, it constitutes only about 25-30 per cent. For many purposes, it is necessary to accurately know how much moisture is contained in wood - in the kiln drying of woods, for instance, or in the manufacture of plywoods. This measure is known as the MOISTURE CONTENT and is expressed as a percentage of the weight of the dry wood matter present.

In practice, the moisture content is frequently determined electrically by means of a resistance measurement, but for accurate determinations a sample of timber is weight then oven dried, with weighings repeated at intervals of about a half hour, until two successive identical weights are obtained, thus indicating that all of the moisture has been driven out of the wood.

Investigations over many years show that timber settles down to a moisture content in equilibrium with the average environment at about 12 per cent moisture content. It will be lower in wood stored in a centrally- heated house and higher in wood kept in a damp cellar. In practice, pipe makers keep a supply of timber blanks in their shops for a selected length of time, at the end of which it is assumed that the timber is suitable for working.

The second of the MISCELLANEOUS DEPOSITS are those laid down in trees as the trunk and branches pass through the transition phase between the actively growing cambium, just below the bark, and the physiologically inert but mechanically supportive

tissue of the heartwood. These deposits in this transition area, which later become heartwood, include silica, mineral oils, resins and gums. Some of these agents provide waterproofing and improve the dimensional stability, as in blackwood. In the case of ebony, the nature of the deposits is different. During the transition phase of tree growth, ebony undergoes a process analogous to, but not identical with, fossilisation.

Having discussed the characteristics of timber for pipe making, we now turn our attention to the subject of AVAILABILITY, which I'll deal with in three chronological but overlapping periods: INDIGENOUS, TRANSITION and EXOTIC. During the INDIGENOUS PERIOD, spanning the 14th to the late 17th centuries, bagpipes were made from local timbers only. We can only surmise at the species then used, but it seems probable that makers used boxwood, hornbeam, laburnum, holly, yew and various fruitwoods.

The TRANSITION period began in the 17th century and lasted, surprisingly, until the early years of the 20th century. During the 16th century, the Spanish, English and French were engaged in bloody rivalry in the West Indies, and by the first half of the 17th century the English were colonising Barbados, St Kitts, Trinidad, Jamaica and other places. It seems reasonable to suppose that for many years afterwards, cargoes shipped to England from these colonies consisted of valuable commodities such as tobacco and spices. At a later time, perhaps during the late 17th century, additional resources such as fine timbers and logwood for dyes began to be exported. In the case of woods for pipe making, these colonial timbers would have become available by the end of the 17th century and would have included cocus wood from Jamaica, lignum vitae from various places in the West Indies and, later, rosewood from Belize, followed by partridge wood from Venezuela.

Parallel to, but later than developments in the West Indies, the fledgling East India Company was laying the foundations for what would eventually become the “jewel in the crown” of the then British Empire - the colonial annexation of India. From the early 1800s onward, gradually increasing shipments of ebony and rosewood from India, together with exotic timbers from the West Indies, progressively displaced the indigenous timbers previously used to make bagpipes. Details of wood purchases by the Glens of Edinburgh in the mid-18th century can be found in Hugh Cheape's excellent paper The Making of Bagpipes in Scotland. (1) The same paper also records the fact that as late as the early 1900s, a pipe maker in Dundee was still making pipes from laburnum and that Robert Reid, whose shop I remember in George Street in Glasgow, remarked of them, “They are all right for lighting the fire with!” Certainly I know of one laburnum set being played in the late 1920s to early 1930s in the Boys Brigade band in which I was a piper.

I consider the time from the early years of this century to the present to be the EXOTIC period since nearly all Highland pipes made in this time have been from imported timbers. Early this century, as cocus wood became more scarce (and remember that there was great competition for supplies from such manufacturers as Boosey & Hawkes for other woodwind instruments), ample supplies of ebony met the demands.

(1) The Making of Bagpipes in Scotland by Hugh Cheape MA, BA,FSA (Scot), pages 596-615, From the Stone Age to the Forty-Five, published by John Donald, Edinburgh, 1983

Concurrently, and particularly after the First World War ended and the UK took over German East Africa (Tanzania), the region was opened up to increased commerce.

Blackwood came on to the market in steadily increasing quantities and, because of its superior characteristics, has in time displaced ebony. I would imagine that from about 1945 all reputable pipe makers have used blackwood exclusively.

It is worth discussing this species in more detail. The distribution runs from the old Anglo-Egyptian Sudan, through Uganda and Kenya to Tanzania, Malawi, Mozambique and the two Rhodesias. It grows sparsely throughout the savanna type of forests called miombo forests which occur at elevations of less than 5,000ft in rainfall zones of 35in to 45in per year and with dry seasons of seven to eight months.

Soils are generally poor and the total of all tree crowns in the forest cover less than 50 per cent of the ground. Botanically, the blackwood belongs to that wonderful genus Dalbergia, which with over 120 species includes such important “musical” timbers as kingwood, Brazilian tulipwood and rosewood, cocobolo, Honduras rosewood and Indian rosewood. The tree is often a scruffy, multi-stemmed runt of 15 to 25ft, but occasionally as high as 50ft.

The species has been heavily exploited commercially but, to put this into perspective, I understand that bagpipe manufacture accounts for about 2 per cent of the volume exported. Much of the miombo forest is being destroyed by shifting cultivation and by excessive burning to stimulate new wet season grasslands for grazing. Regeneration is therefore at a standstill and, since it can take up to 80 years for a sapling to reach commercial size, the outlook for long-term supply is poor indeed. Actual quantities reaching the United Kingdom have improved in past years but this is because Tanzania is no longer restricted to one government agency. Private companies are now exporting, but this means that the existing crop will be cut out all the sooner.

The question arises: from what will bagpipes be made when traditional materials become so scarce that timber is priced out of the market? Various types of plastic have been available for many years, but their tonal qualities are generally unacceptable. In the case of maple (Acer Sp.) impregnated with epoxy resin, the density is in the region of 1.18 and the tone is excellent but, particularly in the case of Highland pipers, there are objections to the cream colour of the wood.

Hamish Moore has produced quite a number of sets of small pipes from an industrial material called Permali which is used mainly as a high-voltage insulating material. Permali consists of laminates of beech (Fagus sp.) impregnated with high-density resin which is then heat-treated and produces a material of a pleasing reddish-brown colour which, when turned on the lathe, appears to have a natural and interesting grain. The material is virtually impervious to moisture, and therefore to dimensional change. Its density is 1.28 and the tonal quality excellent.

This is certainly the best of the substitute materials by far and, for those areas in which extremes of relative humidity occur, it is ideally suited, especially for spall pipes, in the manufacture of which no technical difficulties are encountered, although machining problems may arise in the manufacture of Highland pipes.

This paper, The Characteristics and Availability of Suitable Timber Species in relation to the Past, Present and Future Manufacture of Several Forms of Scottish Bagpipes, is based on a talk given to the Piobaireachd Society Conference at Bridge of Earn in 1991, and later at North Hero, Vermont.

In the beginning ...

THE MAN better known to many as his stilt walking Highland alter ego of “Big Rory” told the Collogue helping found the LBPS was perhaps the thing he was most proud of in his life.

Mike Rowan had trawled through much old paperwork and photographs of the early meetings during the 1980s - “they are distinctly of their time ... hair, stripy pullovers, etc” - and produced the letter he had sent out, at only a few days' notice, in March 1981, calling for anyone interested in Lowland piping to attend a meeting in Edinburgh University's Teviot Row Union

during that year's Edinburgh Folk Festival. “I sent out the invitation to the meeting on the 24th ... it was to be held on the 29th! However, about 15 to establish the society people turned up.” And he read from the letter: “Lowland pipes have become exclusively museum pieces, and are very seldom heard played. I find this very sad, but in my search for a set I've come across several people who were similarly interested... If we all got together I'm sure we could help to raise the Lowland pipe from their almost complete obscurity.”

Mike's interest in Lowland-Border piping stemmed, he said from a lifelong interest in folk music - “I've also always been a socialist, so the people's end of the music spectrum appealed to me, as did bagpipes because they were raw, immediate.” When helping clear out a Boys Brigade Hall in Stockbridge, Edinburgh, that was due for demolition, he found an old half-sized set of bagpipes that he made into a goose (he also found a considerable length of tartan that would become Big Rory's first kilt).

“So I made up a goose and - unfortunately - taught myself to play, so grace notes are not hugely noticeable in my style. Also, I had a childhood connection with Northumberland and enjoyed the Northumbrian pipes, with their beautiful peas-in-a-pod popping and lilting sound, and in 1979 I had joined the Northumbrian Pipers' Society and met Colin Ross, and it was around this time that I learned that there was a lost Scottish tradition of bellows- blown, common-stock “oxter pipes” similar to the Northumbrian half-longs, but no-one

seemed to play them at all.”

Visiting the former Museum of Antiquities - Now the Scottish National Portrait Gallery - in Edinburgh he found a couple of sets on display - “though definitely not in playing order, and I was introduced to Hugh Cheape, who told me about Gordon Mooney, who had been researching Border pipe music.” Gordon, he recalled, could sometimes be seen playing a set of Lowland pipes - made of aluminium. Gordon told him that he and Hugh had been thinking about involving other people in reviving the Lowland pipes but were unsure how. “I suggested forming a group along the lines of the Northumbrian Pipers' Society, and when we asked around we found there was considerable interest but no focus.”

So he sat down in March, 1981, and wrote that letter, while Hugh Cheape and Gordon Mooney between them wrote an article that appeared in the old International Piper magazine which also provoked interest. So from these tentative beginnings, the Society got underway and within two years had 123 members.

Mike also paid tribute to Jimmy Wilson, Pipe Major, lad o' pairts and an early presence at Society meetings, and who was playing Lowland pipes back in the 1960s - when he played them for, among other things, a Drury Lane production of Johnny Armstrong’s Last Goodnight. And Mike produced an old copy of Piping Times which sported a photograph of Jimmy on the cover, replete in his somewhat elfin-like costume for the production.

Jimmy Wilson, recalled Mike, “was an astounding man. He was only that high and had a wee squeaky voice and you might have looked right past him. But once you found out about him - what a character! When I first met him he was an ex-hairdresser, but held also been a regimental piper and had been in the SAS during the war. He was supposed to have been one of the original heroes of Telemark.

And he read from the Piping Times article of 1965: “It's true to say that there is no other piper in the world like Jimmy Wilson. His fame stems mainly from his collecting trades and professions and the technique of playing musical instruments, like some high-class, energetic, artistic jackdaw.” For, in addition to Highland and Lowland pipes, he also played the Northumbrian and uillean models, as well as fiddle, accordion and clarsach.” His pipe bag covers were also in great demand, and Mike reckoned that had he lived in the old days, Jimmy would have been hard put to decide whether to be a piper or a bard, “because he was a natural storyteller”.

And perhaps Jimmy's greatest story, which Mike recounted, was how he was evacuated, along with the other weary troops of the British Expeditionary Force, from Dunkirk. He'd been wounded in the leg by an exploding mortar bomb which blew his boot off, but as his ship approached Tilbury Docks, and he saw the vast crowd waiting to great them, he was horrified when he considered the tired, ragged and demoralised state of the troops around him.

“Jimmy told me that looked at himself: he was bleeding a bit from his bandage but still had his kilt on - ‘ So I looked quite good, really.' So he asked the purser if he could play the troops off the vessel, the gang plank went out and Jimmy started at the top of it with Heiland Laddie and by the time he got to the bottom, the whole mood of the crowd had

changed from one of more or less defeat to one of resistance.

“That was Jimmy Wilson, a wonderful, brave, joyful, creative man.”

At the end of Mike's talk, David Hannay, who was treasurer in the early days of the LBPS, presented him with honorary membership in recognition of his formative efforts.

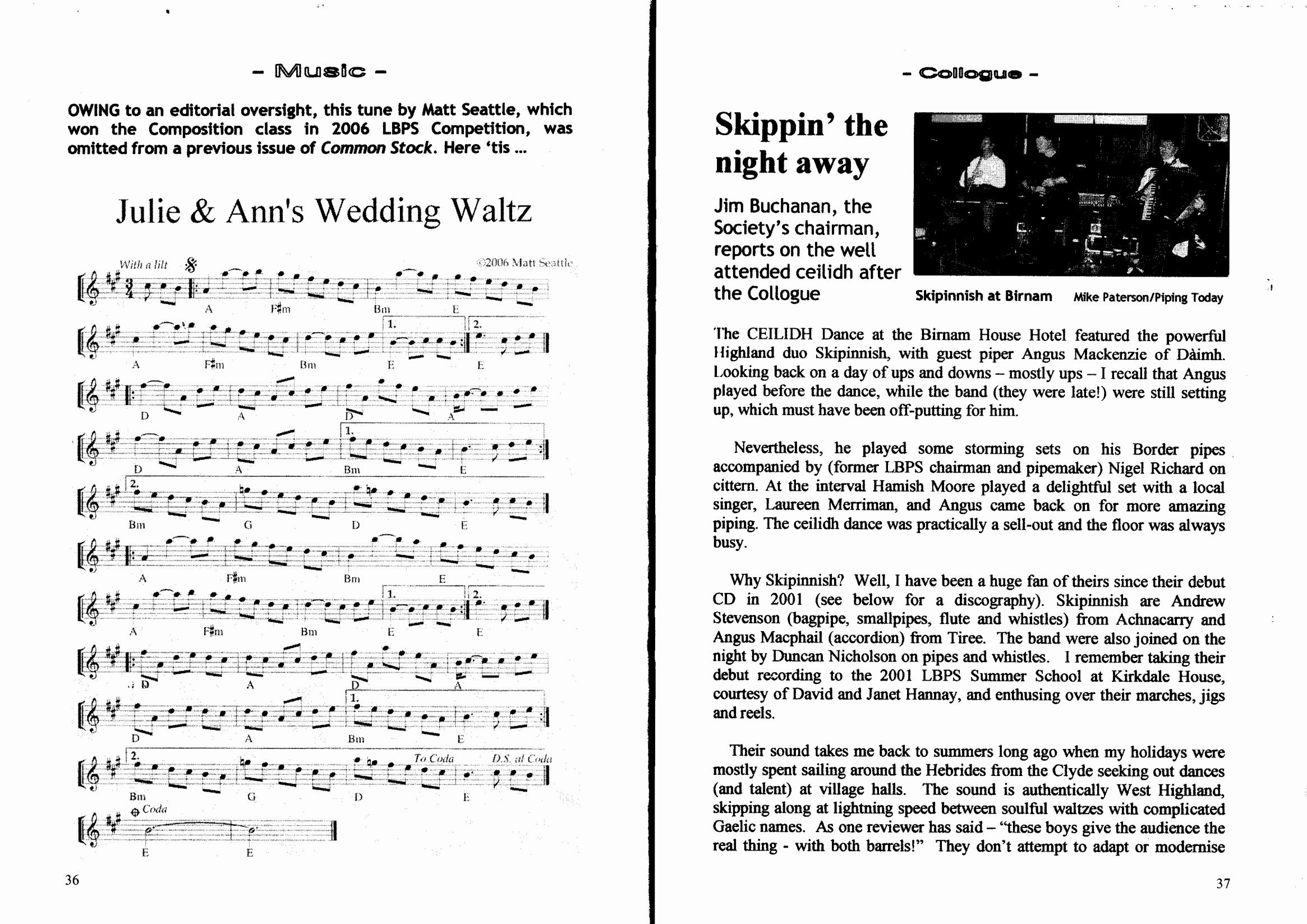

Jim Buchanan, the Society’s chairman, reports on the well attended ceilidh after the Collogue

The CEILIDH Dance at the Bimam House Hotel featured the powerful Highland duo Skipinnish, with guest piper Angus Mackenzie of Daimh. Looking back on a day of ups and downs - mostly ups –I recall

that Angus played before the dance, while the band (they were late!) were still setting up, which must have been off-putting for him.

Nevertheless, he played some storming sets on his Border pipes accompanied by (former LBPS chairman and pipemaker) Nigel Richard on cittern. At the interval Hamish Moore played a delightful set with a local singer, Laureen Merriman, and Angus came back on for more amazing piping. The ceilidh dance was practically a sell-out and the floor was always busy.

Why Skipinnish? Well, I have been a huge fan of theirs since their debut CD in 2001 (see below for a discography). Skipinnish are Andrew Stevenson (bagpipe, smallpipes, flute and whistles) from Achnacarry and Angus Macphail (accordion) from Tiree. The band were also joined on the night by Duncan Nicholson on pipes and whistles. I remember taking their debut recording to the 2001 LBPS Summer School at Kirkdale House, courtesy of David and Janet Hannay, and enthusing over their marches, jigs and reels.

Their sound takes me back to summers long ago when my holidays were mostly spent sailing around the Hebrides from the Clyde seeking out dances (and talent) at village halls. The sound is authentically West Highland, skipping along at lightning speed between soulful waltzes with complicated Gaelic names. As one reviewer has said - “these boys give the audience the real thing - with both barrels!” They don't attempt to adapt or modernise

Highland music to make it suit the ears of a non-Highland audience. As a consequence perhaps not everyone appreciates it, and I did get the odd adverse comments from one or two people at breakfast the next day.

Andrew and Angus first met as students at the RSAMD where Angus studied accordion under Ian Muir and Andrew piping with Allan Macdonald of Glenuig. The band has recently been nominated as Scottish Dance Band of the Year for the Scottish Traditional Music Awards. They are in great demand for festivals, concerts, dances and weddings at home and abroad. I wish them all the best for the future and I'm very glad that I asked them to play for us.

For discography and further information, visit www.skipinnish.com

John Dally casts a player’s eye over Matt Seattle’s most recent tune book, Over the Hills and Far Away

ALL OF us who share Matt Seattle's passion for Border and Lowland pipe music welcome the publication of his latest book, Over the Hills and Far Away (Dragonfly, 2006). While we may debate the relative importance of styles, techniques and ornamentation, and even argue over the definition of what

This new collection of traditional melodies includes revised settings of more than a few tunes published in The Border Bagpipe Book. These revisions, as well as the new tunes, have benefited from Matt's total immersion in the Dixon manuscript. Matt continues his practice of creating settings that are theoretically accurate, and correcting some previously written settings. But some of the changes are not ones this reader will follow, as when he switches out the C sharps for Bs in Holey Ha'penny.

Matt encourages pipers to examine all the possibilities themselves by giving a wealth of background material and freely expressing his own likes and dislikes. The background notes are very valuable and entertaining. As with his previous books

Matt delivers a great deal of historical and scholarly material about the tunes, their structure and history.

Matt's arrangements take syncopation in Border pipe music to the next level and show the influences of blues and rock music. Some of his settings call for technique that might be more difficult than rewarding, as when he jumps to high B and C sharp, but he deserves credit for putting it out there. It is also very much appreciated when Matt supplies backup chords. This reader does not follow his settings note for note, part for part, but enjoys them as potential ways to take the basic melody of a tune, and as suggestions for improving his own style of variation.

One of the more difficult things to get across in any written setting is the underlying rhythm of a tune, especially when we are working with traditions that died out years ago. We come to these tunes largely as readers, so we need all the help our eyes can get. To that end we depend upon the conventions of musical notation to guide our instincts and hard won experience playing the music. Matt's use of time signatures would be more helpful if it were more consistent with convention and if the tying together of the tails of notes followed the time signature.

Suggestions for tempi would also be welcome. Deciphering the fundamental rhythm, through a process of justifying the time signature with the written bars of music, is at times frustrating. When Matt goes a step further by tying the notes' tails together under bar lines to help convey his syncopation, the result, for this reader, is more confusing than helpful.

All musical revivalists cannot escape the influence of their own history and experience, which by definition cannot be that of the music they are attempting to revive. We are always in danger of falling into the trap of historical reenactment on the one hand and arid musicology on the other. The challenge is always to move the music from the page to fingers. It is refreshing to find a piping authority that encourages original thinking and discourages slavish devotion to style or text. Close study of this book will spark many “new ways” with old tunes in the Border pipe sense of the phrase.

(above) Matt Seattle

Meetings and Events

LBPS Summer School, 27 July -1 August 2008, with Common Ground, Scotland at Craigie

College, Ayr. Tuition in smallpipes and Border pipes.

Contact Tom Robertson, 01324 486268.

LBPS Annual Competition, Saturday 5 April at a new venue -

the College of Piping in Glasgow. Watch www.lbps.net for details

Edinburgh - the Scots Music Group at Boroughmuir High School on Wednesday nights.

Smallpipe tutor Lee Moore.

Visit www.scotsmusic.org or phone 0131 555 7668.

Penrith: Annual Pipers' Day - hosted by North Cumbria Pipers on 3 November. Workshops for NSP, SSP and Border pipes, ‘mini' concert, informal sessions.

Contact Richard Evans: This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it. or phone 016974 73799

Glasgow: Celtic Connections - Glasgow, 16 Jan - 3 Feb. Includes many piping events, with this year's guests including Liam O'Flynn, Allan McDonald, Xose Manuel Budino, Fred Morrison, Boghall & Bathgate Caledonia Pipe Band, Bagad Kemper from Britanny and India Alba. See www.celticconnections.com

SESSIONS

North-East England: 1st and 3rd Thursday of the month at the Swan pub, Greenside.

Contact Nigel Critchley 01661 843492.

North-West England: Monthly sessions at Old Crown Pub, Hesket Newmarket. Check with Richard or Anita Evans, 016974 73799

London: 3rd Thursday of every month, except July & August. 95 Horseferry Rd, SW1P 2DX. Contact Jock Agnew 01621 855447

LBPS WEB SITE www.lbps.net